A shift in how we learn

By Mustapha Salaudeen

‘TikTokification’ might sound like a buzzword, but it captures a real shift, not just in how we consume content, but in how we learn. Platforms like TikTok, Instagram Reels, and YouTube Shorts have gradually reshaped our daily habits, offering quick entertainment, micro-escapes, and increasingly, bite-sized answers to some of our unorthodox questions.

For many of us, these platforms have become the go-to for solving problems on the fly, whether it’s learning how to cook a new recipe, understanding a work tool, or simply figuring out how to fix something. And more often than not, someone has already made a 60-second video with exactly the answer we seek.

In our world today, content formats and learner expectations are changing fast, now more than ever before, owing to dwindling attention span. If you could gain the insight you need in just 30 seconds instead of 30 minutes, wouldn’t you choose the faster option? The way we learn is evolving, and for those of us shaping learning experiences, it’s our duty to pay close attention and take note, given the crucial role we play in shaping the future of learning.

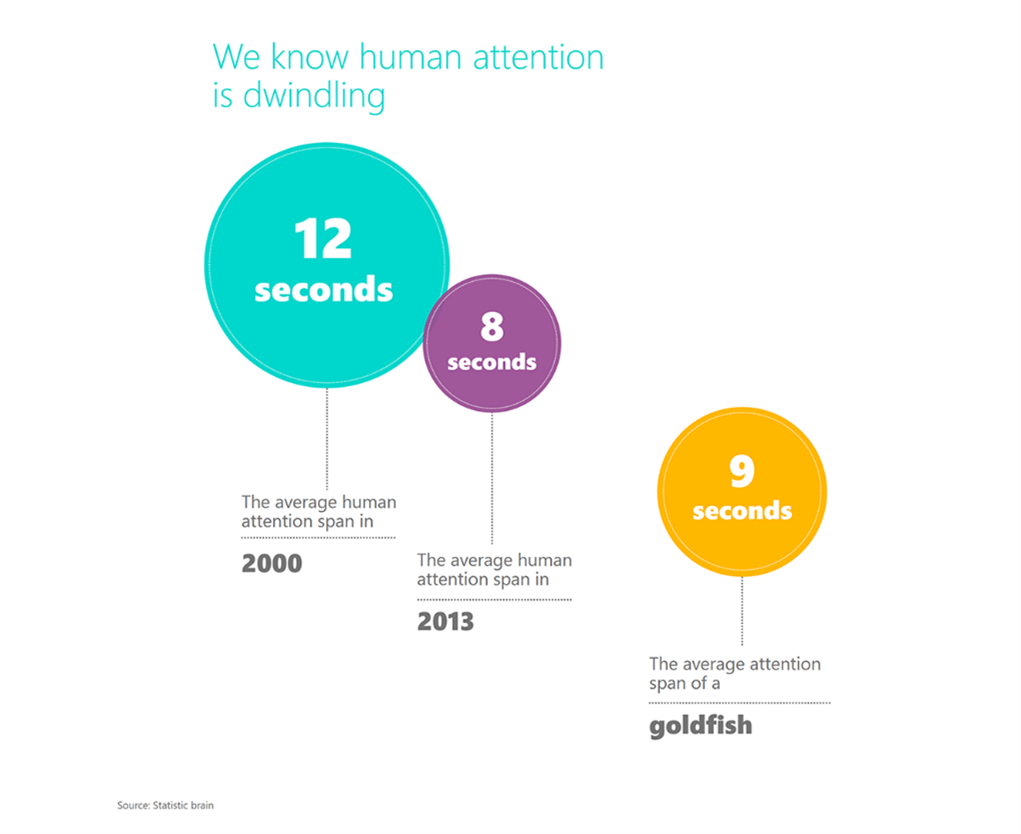

Microsoft (2015) made a bold conclusion from their study of human attention span following a research that surveyed over 2,000 participants, while studying the brain activity of some participants using electroencephalograms (EEGs). The research concluded that the average attention span has dropped by 4 seconds since the mobile revolution began in the early 2000s. This, interpreted in rhetorics suggest that our attention span is shorter than that of a goldfish, a bold but debatable claim (McSpadden 2015). The source of this widely circulated claim has often been challenged and refuted, with some experts arguing that the attention span cannot be precisely quantified (Maybin 2017).

Whether or not you agree with the dramatics of precisely quantifying our attention span, the message is clear: In a world saturated with content, we’ve gradually adapted to favor speed, clarity, and immediacy. The design of learning must then respond to this shift, reflecting today’s cognitive reality.

Behavior by design

The psychology of choice is often one we submit to in our daily interactions: Grabbing a quick coffee on the way to work, voice-prompting devices to answer simple questions like, ‘What’s the weather like today?’, or scrolling for the most engaging video tutorial. As humans, we’re naturally drawn to efficient solutions that offer the highest reward with the least cognitive effort.

It’s easy to argue that this is by design, influenced by certain factors of course, and often involving training our thought process to seek something ‘different’ as an option or to accept a more convenient alternative to what has always been known.

For context, I used to rely on YouTube for help with technical issues. A quick “how to” search almost always did the trick. But I noticed something interesting over time. Sifting through dozens of videos to find one that wasn’t a clickbait became increasingly frustrating, so I adapted. First, I started scanning the comments to gauge whether others found the video helpful. Then I found myself gravitating toward YouTube Shorts, which usually gave me what I needed in under a minute. Before long, this became my default.

This wasn’t laziness; it was behavioral adaptation shaped by design. Owing to cognitive efficiency and reward-based decision-making, we as humans are predisposed to favor options that require less effort when perceived benefits remain equal. Repeatedly selecting the more accessible choice can then solidify into habitual behavior.

The core insight here is that the way we design learning doesn’t just decide how content is delivered. It actually shapes learner behavior and influences how people form habits and engage with content.

As first proposed by educational psychologist John Sweller (1988), Cognitive Load Theory (CLT) supports this claim too. At inception, the theory primarily addressed the challenges people faced when solving complex problems often associated with traditional instructional methods. The theory in recent times is now being looked at in the context of human-computer interaction, where digital learning experience falls (Hollender et al 2010).

According to John Sweller (1988), people learn best when information is presented in manageable chunks that don’t overwhelm the brain’s limited capacity to process new material. His Cognitive Load Theory explains that too much information at once, especially if it’s poorly structured or unnecessarily complex, can hinder learning.

Effective instructional design, therefore, aims to reduce mental clutter so learners can focus on understanding the core message, leading to the conclusion that shorter cognitive bite-size content helps retention, and ultimately, improves the learning experience.

Lesson to learn from short-form content

From a marketing and advertising perspective, it has always been fundamental to factor in audience attention in content generation, sales pitch, poster designs, etc., mostly reflecting the importance of efficiency in marketing strategies. Translating this into a format that is applicable to learning, it’s become imperative to position learners under the same lens and begin to craft learning solutions that fundamentally consider the attention span and the psychology driving learners’ retention level.

Domestika, a creative-focused learning platform, has built a strong reputation through its short, high-quality video modules, often broken into 5-to-10-minute segments. While this does not completely represent the argument suggesting the future of learning is leaning toward even shorter forms of learning, it amplifies the importance of modeling learning solutions to adapt to ever-changing consumer behavior. This approach also highlights the points made by John Sweller in his Cognitive Load Theory about retention level and simplified structure in learning.

Duolingo was also quick to embrace changing learning dynamics and model a learning solution in response, taking cues from Snapchat. Huynh and Iida (2017) analyzed the Duolingo Streak’s effect, with focus on learners’ engagement and motivation, making a comparison between two groups of users. The research concluded that the Streak users are more motivated and attracted to learning than non-Streak- users, based on the differences observed in the measured game refinement values (GR value) of both groups. This further emphasizes that there are lessons to be learned from social media platforms, which can directly be modeled in improving learner’s experience.

Human behavior has continuously shaped platform design, and vice versa. A clear example of this is how TikTok is now championing and democratizing microlearning, especially around everyday skills and quick “how-to” content. We see bite-sized tutorials on topics ranging from gardening and cooking to more complex skills like embroidery, baking, and even financial literacy. More recently, independent creators have begun sharing insights on workplace dynamics, sales techniques, and presentation tips, all of which mirror the kinds of content traditionally found in corporate training, onboarding, or performance improvement programs.

Learning design in practice: Case study

To provide more context on how the reshaped approach to learning content design explored in this article could fundamentally change the way we craft solutions that address real-world problems, consider the following case study.

Imagine you’re a team leader at a food manufacturing company overseeing 50 factory-floor workers. A serious safety incident has occurred. Certain food items were contaminated due to improper handling. Upon investigation, it becomes clear that many workers failed to uphold basic food safety standards, particularly around cross-contamination protocols.

The consequences are steep:

- A product recall costing $500,000

- Production halts costing $10,000 per day

- A damaged reputation and potential regulatory scrutiny

In a crisis meeting, you reflect on the diverse makeup of your workforce, varying languages, education levels, and cultural assumptions around hygiene and food handling. Historically, your training was delivered in classroom-style, instructor-led sessions. You suspect key messages weren’t retained—not because of lack of effort, but perhaps because the format didn’t match the workers’ learning preferences or realities.

You propose a traditional intervention: a one-hour, expert-reviewed course with a final assessment and certificate. But in an environment where employees are time-poor and cognitively stretched, will that have any significant impact on behavior?

What if this learning was delivered in 2-minute bursts, with relatable, scenario-based storytelling, designed to mimic how content is shared on social platforms like Tiktok or YouTube Shorts? Imagine if it also had a live comments section where learners could relate to certain parts of the modules, fostering peer-to-peer interaction.

This raises an important question: Can meaningful knowledge truly be transferred through casual, social-style media? This is a question I’m increasingly curious about, and one that will likely define how learning evolves in the years to come.

Conclusion

Over the past two decades, the way we learn and how learning is delivered has undergone a dramatic transformation. The introduction of digital devices into classrooms marked a significant turning point, shifting learning from passive, instructor-led formats to more interactive, learner-centered experiences. The early 2010s saw wide adoption of digital learning devices and tablets in schools, which opened the door to a new format of learning delivery. While technology progressed over the years, formal curriculum development often lagged behind due to the process of designing and approving curriculum being rigorous and consensus-driven. Thanks to the autonomy to interpret situations fostered by technological advances, and the free will and power to make sense of trends and predict outcomes, both formal and non-formal education continues to evolve rapidly.

In many classrooms today, learners can set up interactive knowledge games, crowdsource facts, or engage in peer challenges in a matter of minutes, covering ground that once required multiple lessons. This isn’t to say depth has been lost, but to outline the key role technology continues to play in the evolution of modern education.

Being a professional in the design of learning experience, I have been at the forefront of how experiences are being shaped by innovative approaches, witness the delivery of novel ideas and their adoption, and measured their impact.

Lately, one question keeps surfacing: What is the future of learning?

It’s an open-ended question, one that invites exploration rather than certainty. But if we look closely at the trends unfolding around us, from short-form content to behavioral design, we may find that the future of learning is already beginning to take shape.

References

- Hollender, N., Hofmann, C., Deneke, M. and Schmitz, B. (2010) “Integrating cognitive load theory and concepts of human–computer interaction,” Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), pp. 1278–1288.

- Huynh, D. and Iida, H. (2017) “An analysis of winning streak’s effects in language course of ‘Duolingo,'” Asia-Pacific Journal of Information Technology and Multimedia, 6(2), pp. 23–29. doi:10.17576/apjitm-2017-0602-03.

- Maybin, D. (2017) “Busting the attention span myth,” BBC News, 6 March. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-38896790 (Accessed: 13 July 2025).

- McSpadden, K. (2015) “You now have a shorter attention span than a goldfish,” Time, 14 May. Available at: https://time.com/3858309/attention-spans-goldfish/ (Accessed: 11 July 2025).

- Microsoft (2015) Attention spans: Consumer insights – digital lifestyles and marketing. Available at: https://studylib.net/doc/8215996/attention-spans—microsoft-advertising (Accessed: 08 July 2025).

- Sweller, J. (1988) “Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning,” Cognitive Science, 12(2), pp. 257–285. doi:10.1016/0364-0213(88)90023-7.

Image credit: rizal999