“It is time again for the present generation of thinkers toinnovate our way out of the dilemmas of the day and build this nation’s toolsof national power that help us with these ideological threats where informationis used as aweapon.”—Lt. Gen. Kwast,Air University Commander (November 22, 2014).

In keeping with the commander’s vision, Air Universityhas continued its search for and development of innovative learning models conduciveto integrated learning environments (ILEs).

In a previous article, we highlighted our journey from Flash-basedvignettes to multi-player educational role-playing games (MPERPGs) in 3-D virtualenvironments to support professional military education at Air University (Arenas& Stricker, 2013). The Squadron Officer College (SOC) has expanded theirsearch for relevant learning models to include an array of the learning toolsnow available in various cloud-computing platforms.

Before we describe our introduction to cloud computing,it is imperative that we understand the relevance of continually addressing thelearner’s needs in the overall education process.

“Staying the course”

Why must educational leaders constantly seek other meansof student engagement? Kapp and O’Driscoll (2010) suggest that the “enterpriselearning function” develops the skills that inevitably direct the competitiveadvantage for an organization. Further, they assert that developing educationwithin a traditional classroom setting as the primary learning modality mayinhibit the abilities of an enterprise to meet the dynamic needs at a timewhen the ability to learn and adapt is becoming a core capability fororganizations. Additionally, they describe the typical learning organization’smain challenge today as the need to “think outside of the classroom.” Moreover,instead of educational leaders arbitrarily incorporating immersive Internetenvironments in classroom-based learning models, they should be considering what kindof learning these new virtual environments may provide.

Although SOC has utilized MPERPGs within the Second Life platform to supportleadership and team-building learning, they have continued their search forfuture virtual-world environments. This research has led to migrating prototypeMPERPGs and SPERPGs (single-player educational role-playing games) within theOpenSim platform utilizing a cloud-based environment. Over the last sevenyears, SOC’s quest to find other interactive methodologies that engage theirstudents at higher levels of learning have led to more interactive educationalexperiences. “It is incumbent upon all educational institutions to seekcreative solutions to meet student-learning challenges” (Arenas, 2015).

Expanding immersive learning models within other venuesnot only offers flexibility for the learning institution, but provides a senseof security in an unpredictable economy. There are several reasons foreducators to explore virtual environments for learning, but probably the mostcited justification is that they “are engaging, fun, and novel platforms forlearning…” (Lindgren, Moshell, and Hughes, 2015).

Research shows that students consistently rate learningexperiences in virtual worlds as more enjoyable compared with other educationalsettings with similar content. Educators should exploit this attribute, giventhe difficulties of keeping students engaged amid competing entertainment technologies.Further, an added bonus of virtual-learning environments is the ability tosimulate experiences that may be difficult to access in real-world situations.

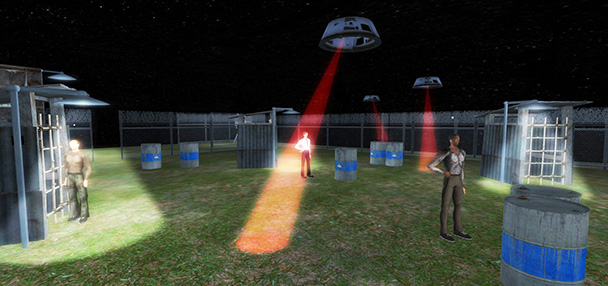

Vassar College, for instance, has replicated the SistineChapel within their Second Life campus enabling students and visitors to studyMichelangelo’s famous ceiling frescos using camera controls or by flying upwardwith your avatar for better viewing (Foster, 2007). In an Air Force setting,hazardous or high-stress scenarios may be replicated in a risk-free setting thatis conducive to active learning. Figure 1 depicts a virtual air operationscenter where Airmen may learn the basic concepts of a complex operationalsetting in a relaxed environment.

Figure 1:Virtual Air Operations Center in OpenSim

Theory relevance

Constructivistlearning theory supports Dewey’s (1966) notion that experiencedrives one’s education; Piaget (1997) described this concept using a cognitivefocus to describe how a child’s knowledge is constructed through exploratoryinteractions with the world.

Moreover, the influence of constructivism has receivedconsiderable attention in the last several decades resulting in inclusion in moreeducational designs. The use of virtual learning environments enables educatorsto create opportunities for learners to become participants in “goal-driven,authentic activities.” This fosters their interaction with objects, systems,and other people and allows them to construct new knowledge during theselearning experiences.

Situatedlearning theory and cognitive apprenticeship allows studentsto engage in expert practices through authentic activity and socialinteraction. Incorporating virtual-learning environments supports situated-learningactivities by simulating not only physical but social contexts as well.

According to Annetta and Holmes (2006), research hasshown that utilizing embodied avatars can lead to high degrees of socialpresence within virtual learning environments and that people interact sociallyas they would in real-world situations. Further, researchers suggest that therelationship between video games and learning utilizes situated learning theoryby requiring context-relevant action while immediately incorporating new knowledge (p.1047).

Virtual learning activities may leverage perceptual and embodied learning by centeringthe properties of participants as physically embodied with a perceptual systemthat closely resembles their capacities for thinking and learning. Gibson andGibson (1955) demonstrated that a participant’s ability to make visualdistinctions between stimuli improved with practice. This realization is ofparticular importance when utilizing a virtual environment, whereby suchstimuli and augmented presentation are controlled and simulated. Theapplications described have limitless boundaries for learners. These range fromembodied avatars to virtual-reality environments where participants mayinteract in immersive spaces while using head-mounted displays to interact withdigital simulation elements, all while moving around in a physical world.

The evolution of our immersive 3-D learning simulations hasintroduced us to the art-of-the-possible in our designs for creating highimpact learning experiences. For instance, we wanted:

- To make use of performance data obtained fromthe 3-D learning simulations and to support just-in-time pre-simulation whileadvancing organizers with follow-up learning-simulation performance reviews thatuse rubrics

- To support interoperability and data exchangebetween learning management systems, mobile applications, and learningsimulations

- To expand our early efforts by applyingconstructivist learning theory in our simulation designs to further extendlearner control by letting them select learning pathways through content andexercises

We turned to cloud computing for help with going beyondour local IT capabilities to implement the art-of-the-possible by creating high-impactlearning experiences that use our immersive 3-D learning simulations within thelarger context of an ILE. Figure 2 highlights one of our popular 3-D learningsimulations, “Compound,” in an OpenSim platform.

Figure 2:“Compound” MPERPG in OpenSim

Integrated Learning Environment architecture on the Cloud

Our integratedlearning environment architecture relies on cloud computing. The NationalInstitute of Standards and Technology (NIST) defines cloud computing as:

Cloud computing is a model for enablingubiquitous, convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool ofconfigurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage,applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released withminimal management effort or service-provider interaction (NIST, 2011).

TheUnited States Air Force recognizes the importance of training and educating theAirman warfighter on-demand, anywhere, at any time. Cloud computing offersversatility for on-demand and integrated computing resources across operatingsystems, databases, mobile applications, learning and content managementsystems, support services, and 2-D and 3-D educational technology applications.

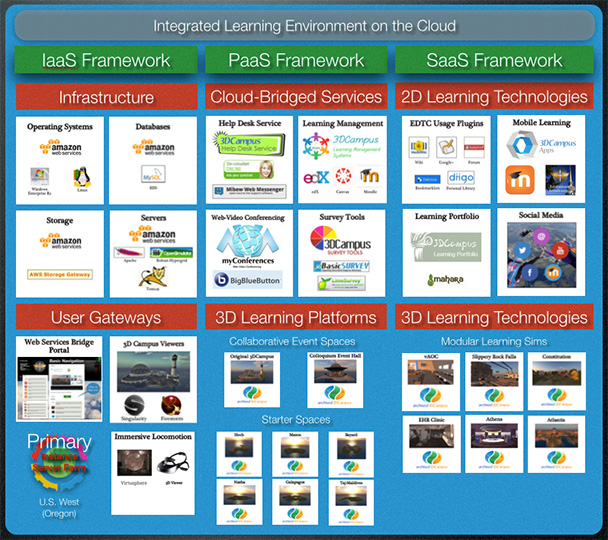

Figure3 illustrates the ILE architecture we employed on the cloud for prototypinghigh-impact learning experiences that use our SPERPG and MPERPG learningsimulations. The integrated learning environment architecture makes use of astandard cloud-stack model for employing interoperable capabilities that make integrativeuse of infrastructure as a service (IaaS), platform as a service (PaaS), and softwareas a service (SaaS).

Figure 3: Integratedlearning environment architecture on the cloud

Asdepicted in the above ILE architecture diagram, we provide access to ourlearning services and simulations using a web portal, immersive locomotionvirtuspheres, head-mounted displays, and client-based software 3-D viewers. Theweb portal, operating on the cloud, offers access to front-end services such aslearning management systems along with access to our 2-D and 3-D learningtechnology applications and simulations.

Cloudversatility features, at the level of courseware and instructional design,include support for integrative application of live, virtual, constructivesimulations as core enablers for the realistic scenario-based learningnecessary for developing successful war-fighting skills and outcomes (Remily,2014). Versatility features, at curricular-program levels, include the means tosupport modular courseware offering blended and connected mixtures of self-pacedand facilitated learning pathways across content using persistent access toshared services (Air University, 2010). We support reporting of interoperabilityand learning analytics across applications with a dedicated learning recordstore (LRS) service making use of xAPI calls across the ILE.

Wesupport self-paced pathways via personalized use of SPERPGs connected toinstructor-facilitated pathways offering cohort MPERPGs. Altogether, SPERPGsand MPERPGs are connected in the course design to support episode-basedlearning activities for tailored conceptual elaboration in authentic andsituated contexts (Reigeluth, et. al., 1999; Lave & Wenger,1991; Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989). We employ spiral instructionaldesign for supporting conceptual elaboration across a variety of instructionalmodules. This involves the application of real-world contexts in the use ofknowledge and skills, delivered in the form of episode- or project-based authenticlearning activities and scenarios sequenced with cascaded complexity and rangesuitable for each individual (Collins, Brown, & Newman, 1989; Schank &Jona, 1991).

SPERPGs andMPERPGs are specifically employed to support the integration, inter-relatedness,and synthesis of ideas or concepts offered thus far in the course. Further, theystimulate two key areas of learning using the learning models of collaborationand role-playing.

Collaborationand teamwork offer many benefits to simulated-learning while placingapprehensive members at ease, lowering stress levels, and fostering coalescenceor bonding in a strange new learning environment. While interacting in thissetting, members often begin to rely on each other for support and mutualcommiseration, leading to stronger teams and creating a “shared experience”factor; a powerful learning tool (Vaughn, 2006). These situations are sometimesreferred to as “CVEs” or collaborative virtual environments, providing similarcharacteristics for a constructivist environment in the form of a virtual setting(Cheney & Sanders, 2011). Students’ ability to practice real-worldscenarios in a risk-free environment is a potent learning modality.

Role-plays arewell-known as a genre of simulation and highly regarded by formal learningprofessionals (Aldrich, 2009). Moreover, concepts are chunked for instructionto help illustrate connected ideas. Chunked concepts are put in the form of instructionalunits and then sequenced as learning pathways. Initially, we offer shorterpathways with each successive path becoming more complex. The goal is tofacilitate greater interaction, deeper understanding, meaningfulness, and opportunityto apply new knowledge and skills. In essence, the SPERPGs and MPERPGs serve ascognitive-strategy activators to build upon present knowledge and skills.

Theelaboration design structure also places emphasis on the development ofself-regulation and reflection for professional-identity development of eachlearner as a reflective practitioner through the freedom to control theselection and use of cognitive strategies. The spiral elaboration of concepts,via learning pathways offering SPERPGs and MPERPGs, assists the learner indeveloping contextualized reasoning and skills to flexibly reframe aperspective to the demands of a situation requiring critical thinking (Schon,1987; Putnum 1991).

Overall, a keydesign goal for the use of learning pathways is to provide personalized andelaborated instruction to help each learner create a meaningful context for newconcepts, expand on them, assimilate them, blend them with personalexperiences, and then reflectively apply the concepts to other (or novel)situations.

Althoughour ILE on the cloud supports use of the Canvas and Moodle learning platforms,we have employed the elaboration design structure using Open edX to helpsupport the modularity of chunked epitomes sequenced and spiraled via learningpathways. Open edX, founded by Harvard and MIT, was launched to support openand massive online courseware.

Thecourseware design tool for edX, named Studio, provides a course designstructure suited for chunking and layering concepts for elaboration. Using edXStudio, you can structure a course to offer epitomes starting with simple andmoving to complex sequencing. edX Studio uses a three-tiered coursewareorganization structure:

- Sectionsare suitable for desired simple-to-complex layers

- Subsections workwell for overviews and advance organizers

- Units containingcomponents are applicable for offering activities that support knowledgeacquisition, discussion, application, interaction, syntheses of concepts, andassessment

SPERPGsand MPERPGs are ideally suited as component problem exercise activity within aunit. You can use subsections to help discern the presence of necessaryknowledge followed with learner control in the self-selection of follow-on unit-learningpathways. Each edX section can also provide for completion certificates used intracking progress, via dashboards and learning analytic tools, regardless ofthe unit-learning pathway taken to complete a section. We employ spiral designas a macro strategy in the integrative sequencing of sections to supportelaboration across the entire course experience for learners. Figure 4highlights an edX course-design structure for chunking and layering conceptsfor elaboration.

Figure 4: edX coursedesign

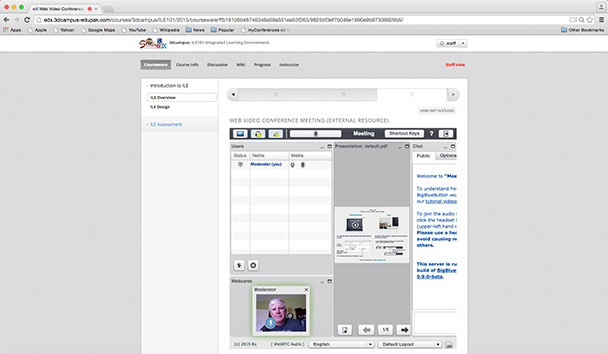

Thevision for creating learning pathways using integrative units provides forlearning content and skills in a meaningful, discrete experience. Each learningpathway offers a context for knowledge application by completing the componentactivities. Upon completing activities across all subsections, the learner isable to demonstrate competency at the level of elaboration the section addresses.Figure 5 displays a shared-component web-video conference meeting.

Figure 5: Web-videoconference

Werecognize there is considerable variety in possible configurations for how youcan structure a course using modular units and components. Our designconfiguration for achieving high-impact learning experiences is based on:

- Sequencing of units from simple to complexelaboration of concepts

- Learner control via learning pathways andincreasing interaction

- Utilizing SPERPGs and MPERPGs and otherimmersive 3-D simulations (allowing learners to apply and reflect on new levelsof understanding and skills through the use of innovative learning tools)

Conclusion

Traditional classroom learning models are not enough toengage, nor sustain active learning approaches for today’s fervent learners.How institutions of higher learning embrace these challenges may directlyaffect their effectiveness and overall future. It is imperative that alleducational leaders advocate for the active investigation and incorporation of integratedlearning environments to supplement their curricula. Changing technology dynamicshas resulted in affordable cloud-based educational opportunities, making itpossible for learning enterprises to access multiple virtual-learning tools theynormally couldn’t afford. It is time for educational leaders to seize such opportunitiesfor the next level of student engagement; immersive learning.

References

Air University. “Modular Distributed Learningand Portal Services via Cloud Computing.” In Horizons in Learning Innovationthrough Technology: Prospects for Air Force Education Benefits, Montgomery,AL: Maxwell-Gunter AFB, Air University A4/6I. 10 June 2010.

Aldrich, C. The Complete Guide to Simulations & Serious Games. SanFrancisco, CA: Pfeiffer, 2009.

Arenas, Fil. J. “Multiplayer Educational Role-playing Games.”In C. H. Major (Ed.), Teaching online: A Guideto Theory, Research, and Practice. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UniversityPress, 2015.

Arenas,Fil J., and Andrew Stricker. “Gamification Strategies for Developing Air Force Officers.” Learning Solutions Magazine. 17 June 2013.

Brown,J. S., Allan Collins, and Paul Duguid. “Situated Cognition and the Culture of Learning.”Educational Researcher 18 (1):32–42. 1989.https://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018001032(accessed 4 June 2011).

Cheney,A., and Robert L. Sanders. Teaching andLearning in 3D Immersive Worlds: Pedagogical Models and Constructivist Approaches.Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference, 2011.

Collins,A., John Seely Brown, and Susan E. Newman. Cognitive Apprenticeship: Teachingthe Craft of Reading, Writing, and Mathematics. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), Knowing,Learning, and Instruction: Essays in Honor of Robert Glaser. Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum, 1989.

Foster,A. The Sistine Chapel Reaches Second Life. TheChronicle of Higher Education. 28 June 2007. https://chronicle.com/wiredcampus/article/2186/the-sistine-chapel-reaches-second-life (accessed 10 April 2015).

Kapp,K.M., and Tony O’Driscoll. Learning in3D: Adding a New Dimension to Enterprise Learning and Collaboration. SanFrancisco, CA: Pfeiffer, 2012.

Lave, J., and Etienne Wenger. Situated Learning: Legitimate PeripheralParticipation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

Lindren, R., J.M. Moshell, and C.E. Hughes.Virtual Environments as a Tool for Conceptual Learning. In K.S. Hale and Kay M.Stanney (Eds.), Handbook of Virtual Environments:Design, Implementation, and Applications, Second Edition. Boca Raton, FL:CRC Press, 2015.

Mell, Peter and Timothy Grance. “The NIST Definitionof Cloud Computing.” National Institute of Standards and Technology. SpecialPublication 800-145, Gaithersburg, MD: NIST, 2011.

Putnum,R. W. “Recipes and Reflective Learning: What would prevent you from saying itthat way?” In Donald A. Schon (Ed.), The Reflective Turn: Case Studies inand on Reflective Practice. New York, NY: Teacher College Press, 1991.

Reigeluth, C.M. “The Elaboration Theory:Guidance for Scope and Sequence Decisions.” In C.M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional-Design Theories andModels: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory. (Volume II).Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1999.

Remily, H. A. TRADOC Cloud Computing.The Army Distributed Learning Program. 11 September 2014.

Schank,R. C., and Menachem Y. Jona. “Empowering the Student: New Perspectives on the Designof Teaching Systems.” The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 1(1).1991.

Schon,D. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching andLearning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

Vaughn, M.S. The End of Training: How Simulations areShaping Business. Golden, CO: Regis Learning Solutions, 2006.