Developing a highdegree of problem-solving skill appropriate to each career stage is animportant function of military training from the recruit level onward. Theultimate goal of this training is agile, adaptive military professionals,particularly the leaders. This is more critical now than ever before.

The US Air Force AirUniversity’s Squadron Officer College (SOC) develops company-grade officers(CGO) into effective leaders (CGOs are second lieutenants through captains).“The Air University uses technology innovations to transform learningenvironments in an effort to keep them efficient, effective, relevant, andadaptable to tomorrow’s challenges,” according to Lt. Gen David S. Fadok, commanderand president of Air University.

In keeping withthe commander’s vision, SOC must continually search for available technologyconducive to the learning management system now in use. After exploring severalvirtual world platforms (Second Life,OpenSim, and Unity), it became evident to SOC staff that Second Life was the right one for our needs. Working with outsideresources, and using Second Life asthe primary virtual-world platform, SOC has designed several multi-playereducational role playing games (MPERPGs) that support their basic curriculum. Inthis article, we will describe how these MPERPGs evolved, their relevancy tothe SOC curriculum, and their importance to future development.

While peopledefine the term virtual world differentlyin various settings in the professional literature, for our purposes virtual world refers to a learningplatform in a computer-based environment. In these platforms, a third-person avatarrepresents the individual learner. (Nelson & Erlandson, in the Referencesat the end of this article, provide additional discussion of the virtual worldas learning platform.)

The virtual trek

In today’s leantimes of dwindling resources, all Air Force organizations must seek creativesolutions to meet mission requirements.Over the last fewyears, the Squadron Officer College has been exploring alternatives to costlystate-of-the-art technology to support their curricula.

SOC embarked on aquest to acquire affordable multimedia in 2008. Initial efforts used Flash-basedavatar vignettes (scenarios) developed by Carley Corporation to support professionalmilitary education (PME) requirements.

Those first avatarvignettes were comprised of short scenes depicting typical situations in an AirForce environment (flight line, hangar, clinic, administrative, etc.). Thescenes highlighted various subjects within SOC’s PME lessons. The vignettes (Figure1) typically run two to five minutes and culminate with a multiple-choice slideto elicit student responses at the comprehension level. For self-directeddistant learners, the vignettes also provide short textual feedback.

Figure 1: Early avatar vignette (2009)

Later vignettes arelonger, with more content, and their design makes them useful for distance learningas well as for resident environments. Beginningin early 2009, the primary use of the avatar vignettes was in a self-directeddistant learning course; nearly 14,000 students to date have used this material.In 2011, SOC delivered these Flash-based vignettes via Blackboard Learn.

Although the overallresponses to the avatar vignettes were positive, global students complained of issueswith connectivity; many students were deployed in locations with limitedInternet access. After producing more than 30 vignettes, staff felt that SOCwas ready to engage their learners in a more immersive learning experience.What was the next level?

Second Life

Underthe guidance of analysts from the Air University Innovations and IntegrationsDivision (A4/6I), our research revealed that as the learning environmentbecomes more complex, educators face many choices of medium delivery. One ofthese choices was the use of virtual worlds (VWs), sometimes referred to as 3-Dimmersive learning environments. Activeworlds,OLIVE, Teleplace, Second Life, and Opensimare examples of the most popular immersive platforms available to educatorstoday (see References, Cheney & Sanders). Most VWs began their evolution inthe early 2000s and continue to develop their technological infrastructures.There were over 200 million registered avatars across nine VW platforms in Juneof 2008. (Wankley and Kingsley, 2009).

Movinginto the virtual world setting would allow SOC to provide more studentengagement and interaction while reducing or eliminating connectivity andaccess limitations. It was clear that going beyondthe depiction of vignettes in 2-D media by providing an immersive learningenvironment and making use of avatars within a 3-D world would advance theeffectiveness of SOC’s curriculum.

Afterthe A4/6I analysts introduced us to the SecondLife virtual world platform, SOC purchased a region for use as a virtualcampus. The A4/6I Division was instrumental in developing a prototype campus (Figure2) to foster learning for 3-D possibilities and promote future research and developmentopportunities that could enhance curricula.

Figure 2:The SOC virtual campus

Why Second Life?

Althoughthere are dozens of virtual world platforms to choose from, Second Life offers organizations flexibilityand a fairly low investment. For a one-time fee of $1,000 per region andmonthly maintenance fees of $295, an organization can purchase private regionsof approximately 16 virtual acres. Comparisons to massive multi-user onlinegames (MMOGs) or massive multi-player online role-playing games (MMORPGs), suchas World of Warcraft and Eve Online, describe common socialattributes such as community building, storylines, and codes of conduct (Kelly& Rhind, 2007).

However,unlike World of Warcraft, Second Life isnot a game, but an open society without gaming rules or levels of achievement.Moreover, unlike Forterra’s Oliveplatform, anyone can enter Second Lifefor free, and spending real money for virtual goods is totally optional forusers (residents), making it a cost-effective virtual world platform (Wankel& Kingsley, 2009).

Bythe end of 2010, SOC had nearly eight months of participation in bi-monthlyA4/6I-sponsored “Lunch and Learn” educational technology sessions, semi-annualGlobal Learning Forums, and periodic VW workshops. Second Life was the chosen platform for two main reasons: It wasinexpensive, and it was server-supported by Linden Labs.

SOC’s learner-engagement goal

Traditionalteaching and learning methods focus on teachers who communicate new knowledge ina classroom setting, where students listen and take notes as required. In sucha setting, students are typically in a passive learning state and often haveminimal participation in the learning process as a whole.

Bycontrast, a constructivist learning approach places emphasis on studentinvolvement, requiring learners to become more self-directed, to be engaged intheir learning process, and to find their own solutions to problems based ontheir prior knowledge and experiences (Cheney and Sanders, 2011). Thefoundations of the constructivist learning approach originate from thecognitive approach to the psychology of learning (Jonassen et al., 1999); these theories were derived fromPiaget (1952), Dewey (1966), Vygotsky (1978), Papert (1980), and Bruner (1985).

SOC’sgoal was to explore methodologies to engage learners, while providing more interactiveopportunities that would further enhance their educational experiences. Throughtechnology, opportunities to apply the constructivist approach to the teachingand learning process provide endless possibilities. Allowing company-gradeofficers to sharetheir military knowledge and experiences with other students while attendingSOC courses has proven invaluable.

The relevancy challenge

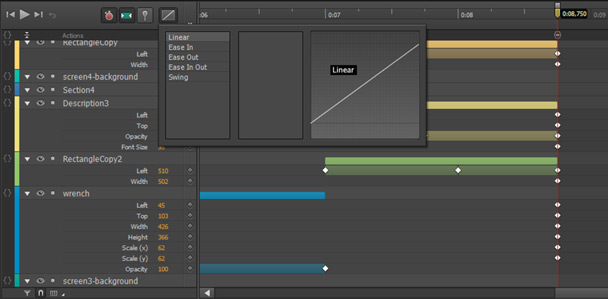

2011brought a new virtual worlds activities project to SOC, using outsidedevelopers from H2 IT Solutions Inc., based in Orlando, Florida. Their task wasto help create single and multi-player educational role playing games(S/MPERPGs), incorporating Squadron Officer School (SOS) lesson materials.Research revealed that gaming and simulation environments support alearner-centered education, whereby learners may actively work through problemswhile gaining knowledge through participation (Annetta et al, 2006). Thecombination of gaming and simulation offers compelling learning benefits whilesupporting immersive experiential learning.

The integratedlearning environment (ILE): Learning in 3-D

Learningin 3-D offers an advantage over 2-D learning environments by providing meansfor learners to experience a sense of immersion in the learning activityitself. The immersion of the learner, through an embodied avatar, makes itpossible to engage with others (in support of peer-to-peer informal learning),while also participating in facilitator-guided experiential learning activities.This promotes comprehension and application of formal learning objectives (Kapp& Driscoll, 2010). The technology behind learning in 3-D helps to createthe spatial and temporal conditions for immersion and interactivity with othersand with content in the performance of tasks requiring the application of newknowledge and skills.

A team of subject matter experts andmedia specialists collaboratively used instructional systems design (ISD) andrapid prototyping to develop eight immersive 3-D learning activities. These interactiveteam-building challenges engage SOC students in experiential problem solving learning.The challenge design also promotes cognitive strategies for problemidentification, analyzing options, and self-regulation of performance forsuccessful outcomes. With the use of imagery and soundeffects, the activity provides a challenge scenario that mimics and convertslive-action problems, ensuring a sense of stress and urgency. Figure 3 depictsone of the challenges that requires a team of SOC students (using avatars) toeffectively problem-solve together and rescue a set of team members from asimulated prison compound within a limited time.

Conclusion

Evaluationof the learning activities offered in an ILE for learning in 3-D suggests that SOCstudents value the immersive features of the environment and the opportunity toapply new knowledge and skills in collaborative, context-based problem-solvingchallenges. The eight interactive team-building challenges allowed SOC studentsto experience operational adaptability involving cognitive strategiesassociated with critical thinking, prudent risk acceptance, and rapidadjustments informed by continuous assessment of unfolding events.

Overall,offering learning activities in immersive 3-D ILE environments provides themilitary learner with valuable experience to process information intoknowledge, then share that knowledge and act on it to solve challenges todevelop agile and adaptive leaders with the skills necessary for the professionof arms in the 21st century.

References

Almanac 2012-13, Chronicleof Higher Education, vol. LIX, no. 1, (2012), 53.

Annetta, L., Murray, M., Laird, S., Bohr, S., andPark, J. “Serious Games: Incorporating Video Games in the Classroom.” EDUCAUSE Quarterly Magazine, 29(3),16-22. In S. Hai-Jew, Virtual Immersiveand 3D Learning Spaces: Emerging Technologies and Trends (p.273). Hershey,PA: Information Science Reference, 2010.

Cheney, A., & Sanders, R.L. Teaching and Learning in 3D Immersive Worlds:Pedagogical Models and Constructivist Approaches. Hershey, PA: InformationScience Reference, 2011.

Dewey, J. Democracy in Education, An Introductionto the Philosophy of Education. New York: Free Press, 1966. In A. Cheney & R.LSanders (Eds), Teaching and Learning in3D Immersive Worlds (p.186). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Jonassen, D.H., Peck, K.L., & Wilson, B.G. Learning with Technology: A Constructivist Perspective. Upper Saddle River, NJ:Merrill, 1999. In A. Cheney & R.L Sanders (Eds), Teaching and Learning in 3D Immersive Worlds (p.186). Hershey, PA:Information Science Reference.

Kapp, K. M., & O’Driscoll, T. Learning in 3D: Adding a New Dimension to EnterpriseLearning and Collaboration. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley and Sons, 2010.

Kelly, T.S., & Rhind, A. Marketing in Second Life and Other VirtualWorlds. Media Contacts: Havas Digital, 2007.

Nelson, B.C. & Erlandson, B.E. Design for Learning in Virtual Worlds. NY:Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2012.

Papert S. Mindstorms: Children, Computers, andPowerful Ideas. New York: Basic Books, 1980.In A. Cheney & R.L Sanders (Eds), Teachingand Learning in 3D Immersive Worlds (p.186). Hershey, PA: InformationScience Reference.

Piaget, J. The Origins of Intelligence in Children.New York: International Universities Press, 1952. Doi: 10.1037/1149-000. In A. Cheney& R.L Sanders (Eds), Teaching and Learningin 3D Immersive Worlds (p.186). Hershey, PA: Information Science Reference.

Secondlife.com, PrivateRegion Pricing, https://secondlife.com/land/privatepricing.php (accessed 22 Oct. 2012).

Vygotsky, L. Mind in Society: The Development ofHigher Psychological Processes.Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1978.

Wankel, C., & Kingsley,J. Higher Education in VirtualWorlds: Teaching and Learning in Second Life. UK: Emerald Group PublishingLimited, 2009.