For over a hundred years, human resource management (HR), as well as training (or learning and development (L&D) as we call it now), has been more of an art than a science. Today, with better systems for measurement and computation, we are learning that those organizations that pay attention to “big data” and act on it compete more successfully. The same is true for HR and L&D: groups that can apply the science provide strategic contributions to business success. This goes far beyond ROI measurements.

How can you measure the impact of L&D investments? How can you increase the results from the investments that succeed?

I interviewed Gene Pease, founder and CEO of Vestrics, about these questions.

The evolution of human resources management

Bill Brandon: How does human capital management relate to human resources management? Are they the same thing, or has something new been added?

Gene Pease: Human capital management and human resources management are really the same thing. The profession has evolved to be more sophisticated than what we used to call just “human resources” or “HR.”

HR historically grew out of the support functions for payroll and keeping employees employed. Human capital management implies more sophistication, based on the body of work that’s been done over time in different fields in HR. That would include leadership development, recruitment, employee engagement, and so on. Now analytics is adding to that body of work, by using the power of computers and applying the decades of study that have gone into figuring out how to answer some complicated questions.

It seems to me that human resources management is now evolving into human capital management because it is getting more strategic and has a say in, hopefully, analyzing strategic decisions. The change is driven by our knowledge of things working and not working, and technology, and analytics. I think it’s all part and parcel.

BB: Are there other drivers besides technology and analytics?

GP: Well, I think there’s a lot of factors driving change. Market conditions are forcing change. The Boomers are retiring, the Millennials are coming up, and different approaches to learning, along with the use of technology, particularly wireless and mobile-delivery mechanisms, can provide content at the point of need. It’s economic conditions, with demographic changes, at least within US organizations—although the world is not that much different to us, at least to what I understand from a demographic point of view. So I think there’s a lot of factors driving change.

Talent development and learning and development

BB: What’s the relationship between talent development and learning and development? Is there some kind of intersection or is there an area of overlap?

GP: There are multiple definitions of these terms, and they absolutely overlap. Some people believe leadership development would be under the umbrella of learning and development, which could be under the umbrella of the chief learning officer or a corporate university. At the same time, other organizations say leadership development is under talent development, not L&D and the corporate university. Now, it seems to me we’re trying to develop our talent, our human resources, both to make them happy, be more productive, and stay longer, and to be more productive for the organization and to get a return on the investment in people.

In my opinion, you’ve got to ask, “What investments are we making in the life cycles of our employees to develop them and how do we get something from the investment for the organization.” I think it’s both. When we do analytics, we always look at the people impact. Does it help the groups of people and the individuals on the job? Are they more engaged? Are we progressing people in the organization? Then we always look at the impact of the investment on the organization’s strategic goals or on the optimization of that investment.

BB: The half-life of knowledge these days is said to be about two years, meaning that an engineer coming out of school with a bachelor’s or even a master’s degree, by the time that engineer has found a job, half of what the engineer learned is outdated. Isn’t that the reason for learning and development?

GP: We’re getting smarter at knowing that every person doesn’t respond the same way as everybody else to different things. To me, the whole idea is segmentation. When I speak about this stuff, I talk about HR, or talent, or whatever group you want to assign this work to, often pretty much spreading the peanut butter equally so they give everybody the same onboarding program. Now we know that a single program probably doesn’t work as well for everybody. Today we can begin to talk about segmenting, so that, for example, different populations of people probably should get different flavors of the peanut butter in an onboarding program. And you can go down the line with all the investments we make in people throughout their life cycle and you can begin to segment or optimize those investments by being able to fine-tune them. That’s the power of what we know how to do today.

The continuum of analytics

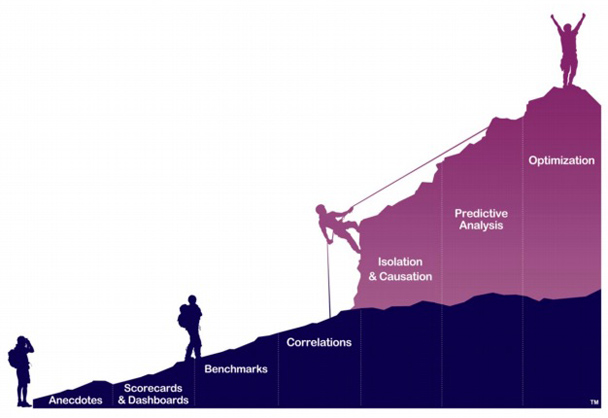

BB: So let’s move to the big question: What is human capital analytics? Is it related to return on investment (ROI)? Do we still need to calculate ROI? I’m looking at the Continuum of Analytics in Developing Human Capital (Figure 1), and I also note that you and Jack Phillips were speaking together at a recent conference. I wonder how your points of view compare and contrast?

Figure 1: The Continuum of Analytics

(Source: Developing Human Capital.

Used with permission.)

GP: Well, Jack and Patti and we at Vestrics are working on a series of initiatives and partnerships. They believe (as I believe) that our work is complementary and adding onto the body of work that Jack has done. I’ve given up arguing that the information you see on dashboards is analytics. I don’t believe it is, but I’m not going to argue with the industry any more.

The data that comes out of dashboards, the activity metrics of those departments, is the beginnings of analytics work. How many people took courses out of the LMS is important and is background information to data-mine. That’s where we start with data.

Getting to a business impact is part of that work. We must try to identify the impact these investments have on the outcomes that we’re trying to change, from a business point of view. What value can we put on that financially?

ROI is just a calculation of the cost of an investment versus the benefit. In other words, ROI is part of the continuum of doing this work. The exciting stuff, the stuff that we’re doing, is getting beyond that and getting to really isolated business impact and ROI. This means you can then understand where the investments are working and where they’re not. When you’ve done that, you can get into the world we live in, which is the predictable: we understand the relationship of all the different variables and the investments we made, and then we can, with high predictability, model the optimum ways to make that investment, both from the people point of view and the organization’s point of view.

As you move up the continuum, the work gets more sophisticated. We built the graphic of our continuum with a mountain because the analogy is, the higher you get, the harder the climbing is, but the better the view. And that’s really what is true with this work. That’s how we define analytics: it starts with the data coming out of the dashboards and you get more sophisticated as you pull in data from other sources, and you do some sophisticated statistical analysis with that data.

BB: I have heard people say you no longer need to bother with ROI.

GP: You may not. Let me tell you why. Let’s say that you have an investment and you get all of the anecdotal and survey-based information back and it’s positive. You’ve calculated ROI a year ago on the same program—if it continues to show the same kind of evidence, then I wouldn’t calculate ROI again. I would say, okay, how do we know, what have we learned to improve it? We’ve already proven the investment pays for itself, now let’s focus energy on making those improvements. In that instance I would say you don’t have to recalculate ROI. But if a learning person says you don’t have to calculate ROI, then they’re still talking in HR-speak and they’re not talking the business of business. That’s part of HR’s problem. Historically, they haven’t spoken in the financial vocabulary often enough, so that the chief financial officer doesn’t give them as much credence as they should in understanding their business.

The measurement plan

BB: If a chief learning officer or a director of training decided that he wanted to go this route, what should he or she include in the measurement plan for learning and development?

GP: First, you would create a series of “filters.” That is, a series of criteria for the importance of certain investments. They could be defined as “our largest investments” in training programs, from the largest on down. Or they could be according to corporate strategic importance. For example, sometimes leadership development is not the most expensive investment an organization makes, but it might be the most critical. So you set up a series of criteria, or filters, for making decisions about how sophisticated you want to be and how much time you want to spend in understanding the impact of these programs.

When you begin to rank those criteria according to requirements for your personal bandwidth and time investment, all of those variables, you then begin to have a strategy for measurement.

Maybe some things are okay not to measure. For some training programs, levels 1 and 2 survey data might be fine, because you have evidence they’ve worked in the past. For the ones we’re going to allow using levels 1 and 2 surveys on, we’ve already got some system in place that seems to work and the data seems pretty accurate so we’ll leave them alone.

Then you want to move up, according to the way you defined the continuum. We always recommend getting into some really sophisticated measures, gaining real understanding, and making real improvements—those are the most important for the largest investments or for the most strategically important. That sets the framework, what we call the “framework for measurement.”

Depending on where you are in the framework, depending on the tools you use, and the sophistication used for the measurement, you’ll have a very specific plan on where to measure and where not to, and on when to and when not to.

For the sophisticated work, we’ll have to figure out some things. Do we have the internal resources, do we bring a consultant or technology in to help and to help teach us, or do we self-fund—build our own internal analytic department? That becomes the investment decision.

A lot of the work we did in our early days, before we built a technology solution, involved coming in and doing initial process for companies. Now clients ask us to teach them how to do the work as they build internal departments to be able to do the sophisticated work. It’s a kind of an evolution once companies get started in this.

Analytics

BB: At what point does predictive analytics come in? How does that work?

GP: Predictive analytics can involve determining strategy, and it can be used to improve the investments you’re making. When you’re making investments such as sales training, in a large organization you may be training thousands of people. We’ve measured programs that trained thirty thousand, fifty thousand people. You know you’re going to be investing in that sales organization, because the sales people drive revenue and gross margin. How can we make sure, number one, that the training is working, but more importantly, how can you figure out how to improve it? That’s where you do the really advanced stuff.

That’s not predicting a program, that’s optimizing the program you’re currently doing. It’s using the predictive capabilities of analytics to optimize your investments. That’s how I would refine predictive analytics versus optimization of an investment. One is the tool to get to the other.

BB: Can you give some examples of organizations that have done this?

GP: I think we have fourteen published case studies that are on our web site or in the books. (BB: See References at the end of this article.) Most of them are with organizations you would know: ConAgra, Sun Microsystems, USBank, Chrysler. A lot of stuff in L&D and leadership training—quite a few of them.

Alignment and optimization

Let’s go back to predictive analytics for a minute.

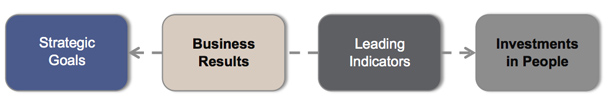

This is how we do alignment. [Figure 2] is how we view the world, based on our framework and methodology. After eight or nine years of consulting, we’ve changed our vocabulary and you’ll notice we don’t use the word “KPI” [key performance indicator].

Figure 2: Measurement map

(Source: Developing Human Capital.

Used with permission.)

We think about an investment in people and that could be any of the things we’ve talked about—it could be a program, it could be an individual curriculum, an individual course; it could be a process change like performance management; or it could be anything in L&D. We then identify the leading indicators, and those are the things you cannot put a financial value on but that show proof you’re on the right path. You hypothesize by thinking about these. And then we get to what business results we think we want to change or impact, and does that tie into the strategic goals of the organization? And the strategic part, a lot of HR or L&D people don’t have a clue what their corporate strategic goals are. So we kind of force them to find out.

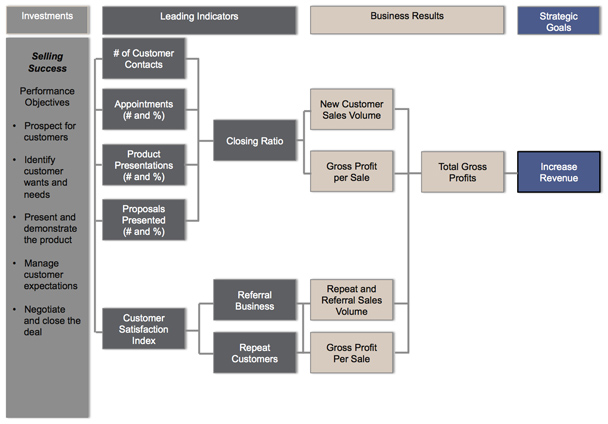

Figure 3 is a specific example of what we call “building the alignment.”

Figure 3: Alignment example for “Selling Success” course

(Source: Developing Human Capital. Used with permission.)

Suppose we have a program called “Selling Success.” You see in the bullet points the goals of the program. We believe that if we successfully deploy that program we might increase customer contacts, might increase appointments and presentations, and so on. If we increase any of those (which we define as leading indicators), the closing ratio may go up. I’m hypothesizing this is what this course is going to change. If my closing ratio goes up, I will increase new-customer sales volume, gross profit per sale, and so on, and this increases gross profit, and that ties into strategic goals.

When we have organizations build these maps, just thinking about the alignment and having a framework that’s visual gives people much more clarity. We have instructional designers who are using the lower end of our software to build these maps. You can do it virtually, and then you can share it. The beauty of doing it this way is that these boxes then define the study. They tell you what data you need to start doing the statistics to identify which variables are affecting other variables.

This is what we call alignment. We give workshops in very small companies to teach people to think this way. In large companies you can do the advanced statistics and the predictive analytics. Now you really don’t need to do the predictive analytics in order to get to alignment. The analytics are just a very advanced statistical tool if you have a lot of data and you want to get sophisticated and fine-tune your investments.

We think about this whole world of alignment in two different chunks. We think about it first as setting up the alignment—how do you build the map, what’s behind the map, what data I might need—and second, how do we use alignment in order to support either simple or very advanced analysis of the data. We do the analysis to answer the following business questions: are my investments working, where are they working, and where are they not working. Is my curriculum delivering—is that curriculum we designed to hopefully increase the closing ratio and so on, is it really doing that, or is it only affecting a few of those indicators and the people taking the course aren’t getting the other three things the course was intended to deliver. That’s what you can measure with this approach.

What next?

BB: Gene, is there anything particularly important that you think the readers really should know?

GP: We know through at least a couple of different surveys that less than 7% of US organizations of mid-size or larger have a dedicated analytics department within L&D or talent, whichever term you use to define that broad umbrella. L&D and talent groups have a huge opportunity to move quickly if they choose to. It’s that other 93% that we have to encourage to do more advanced measurement of the activity of the departments, beyond just pulling numbers and assumptions from dashboards.

Get going! Start small and get going! Start building an expertise! There’s a lot of information from studies on those enterprises that are really, truly data driven that show they are out-performing their competitors. We know human capital is the most important asset a company has today, driving innovation and everything else.

We’ve got to get better at making those investments in people count. We can do more advanced work now. Ten years ago, when we started doing this work, it hadn’t been done before. Now the industry has a decade of experience. Some of us believe L&D (or talent) is where marketing was 10 years ago. Think back 10 years ago, and then think what marketing is doing now with data. Unbelievable things. We could be doing the same thing in HR. That to me is the opportunity we all have.

References

Pease, Gene, Boyce Byerly, and Jac Fitz-enz. Human Capital Analytics: How to Harness the Potential of Your Organization’s Greatest Asset. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

Pease, Gene, Bonnie Beresford, and Lew Walker. Developing Human Capital: Using Analytics to Plan and Optimize Your Learning and Development Investments. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2014.