If the sticker on the box says theproduct is, “Engaging,” is it?

The word “engaging” is probably the mostoverused word in the ever-evolving world of e-Learning. Vendors like to saythat their courseware is “engaging.” But is clicking on a button labeled “Next”after reading through an onscreen passage engaging? Is answering a simplemultiple-choice quiz engaging? What about listening to a narrator read words ona screen? Is that engaging? Do any of these things capture the attention of ouraudience and sustain it? Do the typical interactions found in most e-Learningcourses pull learners into an experience and entertain them? In most cases, doour learners even remember the experience after they’ve clicked the “Exit” button? Sadly,many probably don’t.

Of course, no one ever sets out tocreate a “bad” course. But, faced with corporate constraints of time, budget,and the occasional pesky manager, we often fall into our comfort zone — andcreate what we know will get the project off our plates. That usually meanscreating a course that follows the traditional, linear instructional model oftelling and then testing.

This is too bad, because there’s anothermodel out there that truly is engaging. It’s a model that immerses its participantsinto experiences that demand purposeful interactions. It’s a model that givesparticipants concrete, real-world goals to strive towards. And it’s a modelthat its participants willingly embrace. So much so that many of them will waitin long lines at big electronic gadget stores and pay serious money to embraceit.

Of course the model I’m referring tohere is the modern video game model. So, are your eyes rolling yet? I hope not,but some people seem to hold the belief that learning can’t take place if funand games are involved.

I’m one who happens to disagree withthat position. This isn’t to say that I think our learners should be shootingaliens while learning about Sexual Harassment or chasing cute, multicoloredghosts while learning about something like Workplace Violence. “Fun” in my minddoesn’t mean cute characters or abstract animations. Fun, to me, is the absenceof boredom. Adopting a modern video-game model does not mean alienating learnerswho are turned off by games. It means adopting a model that incorporates someof the most compelling elements of today’s immersive, simulation-based videogame experiences.

Playing the policy game

In a lot of today’s video games,players do battle with ogres, or aliens or other incarnations of evil. Well,the incarnation of evil that we had to deal with at Allstate was something muchworse. It was the dreaded Human Resource Policy Guide!

Our team needed to develop acurriculum of required courses based on these infamous, yet vitally important,HR policies. The courses in the curriculum (eventually called the AllstatePolicy and Compliance Curriculum or APCC) include: Information TechnologyUsage, Ethics and Integrity, Sexual Harassment/Non- Discrimination, andWorkplace Violence.

To create the APCC, our teamdesigned and implemented a courseware approach we dubbed “Digital Experiential Learning”or

During this article, I’ll use the“F” word a few more times, while explaining the approach we took at Allstate todeliver online human resource policy training. I’ll get into the instructionalelements we used to help enable retention, the gaming elements we used tosustain motivation, and the simple in-house technology we used to build thesecourses. I’ll also talk about the reactions our audience had to the

Why the new approach?

There were four facts driving thedevelopment of this curriculum. The first fact has to do with the way thepolicies are written. They’re written in the preferred language of most policydocuments — “legalese.” And for those of you who can read legalese —congratulations! But for the rest of us, me included, legalese is moredifficult to wade through than a passage from a high school Latin book. So thecourses needed to be easy to understand. The second and most important reasonwe were looking for a new approach to delivering this content was that wewanted to be sure employees “got it.” This was especially important in light ofthe fact that they could be terminated if they didn’t “get it.” The third driverin our overall development was we wanted to be sure that our audience retainedwhat they learned.

But there was also a fourth fact,and it had to do with motivation. If someone tunes out of our course after thefirst few screens because they’re bored, then nothing else really matters.We’ve lost them. We often assume that adult learners can find a way to“self-motivate” when they feel that the content benefits them in some directway. But in this situation, the content really tested that assumption. In ouropinion, traditional e-Learning wasn’t going to cut it. We needed somethingmore.

We needed something “engaging.” Moreimportantly, we needed an approach that kept learners motivated while alsoenabling content retention. We needed something that was FUN. But it alsoneeded to be something that would be taken seriously, as the subject matter demanded.It needed to be an approach that was grounded in the real world, not just avideo-game fantasy.

The recommended approach, and the oneagreed to by our internal clients, was the proposed “Digital Experiential Learning”approach. I’ll describe some of the key elements of the

Instructional elements of a approach

The most important outcome of any e-Learningcourse is for people to remember what they learned. That’s a “no-brainer.” TheAPCC plays an integral role in ensuring that employees are aware of and incompliance with important company policies. Due to the nature of these policies,and the fact that employees could be terminated if they were not in compliancewith the policies, content retention was an imperative. We couldn’t just dumpthis content into one of our traditional e-Learning templates and assumeretention would magically take place. Learners needed to retain corporate policyknowledge, comprehend its meaning and be able to apply it back on the job. Tohelp ensure that all of this takes place, the courses have several instructionalelements at their core:

- Simulation-based

- Levels, not lessons

- Cognitive apprenticeship

- Conversational writing style

- Driving learners to the tools

Simulation-based

Many e-Learning courses follow the traditional“tell” and then “test” model, meaning that learners go through a few screens ofcontent and are then tested over it. If they’ve transferred the content to theirshort-term memories, they’ll do well.

Our approach effectively reversedthis, arguing that transferring facts to your short-term memory may be justfine if your goal is to get your learners to pass a multiple choice quiz. Butif you want your learners to be able to apply what they’ve learned six monthsdown the line, performance, not rote memorization, is what your goal reallyought to be. In the design of the APCC courses, we took an approach that was,essentially, “test” then “tell.” Learners are immersed into situations wherethey’re forced to perform. This is the “test” part. They’re free to makemistakes, in a safe, online environment. The “tell” part comes later, in theform of immediate feedback from a “guide” character who is the learner’s mentorthroughout the course. It is in these situations where “teachable moments” arelikely to occur.

What, exactly, is a teachablemoment? Well, to me, a teachable moment is the ultimate attention grabber. It’swhat happens to you the moment after you’ve gotten your hands caught in thecookie jar — or opened up a virus that crashes your hard drive. Essentially, ateachable moment is an uncomfortable situation that urgently focuses yourenergies, and attention, on making sure that the uncomfortable situation is neverrepeated.

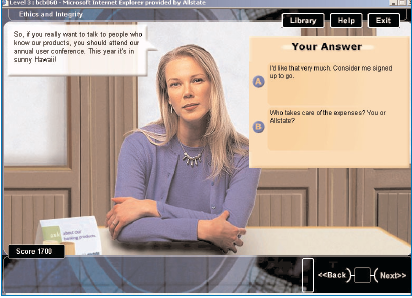

One such “teachable moment” becameclear to us during a user group debrief session we conducted. During thatsession, we had a group of about twenty people go through our course on Ethicsand Integrity. After they completed the course, we talked to them about theirexperiences. One user went on at length about how she got “Sue” into troublebecause she was unsure of Allstate policy on accepting gifts from vendors.“Sue,” was a character in the course. But she learned from her experience with“Sue,” and later on was able to deal appropriately with another character inthe course in a similar situation (see Figure 1). Simulations allow us toset the student up into uncomfortable situations that can lead to the teachablemoments.

Figure 1 An example of a “teachable moment.” A simulation from Level 3 of our course, Ethics and Integrity.

Levels, not lessons

In a traditional e-Learning course,content is often modular, or “lesson-based.” Learners start out in the firstlesson, and progress through various topics until all have been completed. Eachlesson covers a new piece of content.

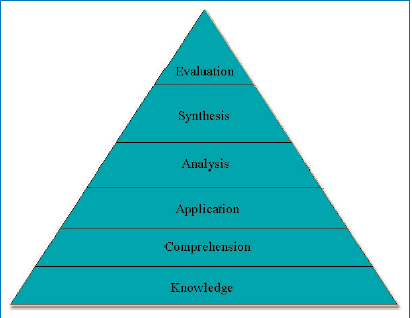

Our courses approach learning quite differently.The APCC courses are “level based,” not “lesson based.” Each course is made upof three levels. For each “level,” learners experienced all of thecontent. In succeeding levels they are exposed to the same material, but at aslightly higher level of difficulty. This idea of levels, while fitting innicely with the entire video-game feel, actually had to do entirely withBloom’s Taxonomy (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 The six major categories in Bloom’s Taxonomy. Here they are listed in order starting from the simplest behavior (Knowledge) to the most complex, (Evaluation). Our courses progress through only the first three.

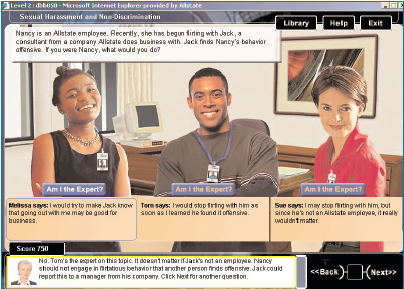

In Level 1 of a course, learnersprogressed through all of the content, but at a knowledge level. For example,Level 1 of the Ethics and Integrity course covered basic facts and terminology(see Figure 3). In Level 2, learners moved through the same content, butat a comprehension level. We were looking to see if they grasped the conceptsand could predict consequences. Finally, in Level 3, learners engaged insimulations to see if they could apply the content in real world situations.(See Figure 4.) The end result of a level-based design is that learnersgo through the same content, but see it in varying contexts.

Figure 3 An example of a Level 1 interaction from the Ethics and Integrity course.

Figure 4 An example of a Level 3 interaction. In this example, the learner needs to apply what was learned in Levels 1 and 2.

The level-design approach was key tolearner retention in the APCC courses because our audience was able to practicetheir skills in varied and increasingly more complex contexts. Brenda Sugrue, inher 2002 article, Practice Makes Performance, states that a key element toknowledge transfer includes opportunities to practice skills in variedcontexts, with monitoring and feedback that identifies and correctsmisconceptions and faulty reasoning.

Cognitive apprenticeship

So we incorporated Bloom’s taxonomy intothe overall instructional design of our courses and let them apply their new skillsin real-world simulations. Another element of our instructional approach wasthe idea of a cognitive apprenticeship — a term defined by Kevin Oliver in his1999 article, Situated Cognition and Cognitive Apprenticeships.

As Oliver explains it, a cognitiveapprenticeship is designed to build expertise through online, guided discovery.Just as it’s often easier to learn a foreign language through immersion, wefelt that the best way for our audience to fully grasp mundane policy knowledgewas to immerse them into realistic situations. In our courses, learning oftentook place just beyond what our audience knew, but not at a level ofimpossibility.

For example, there was one situationin a course where learners had to help a colleague who is constantly being passedover for promotions. This colleague happens to be gay. While the learner maynot yet know how to solve this complex issue on their own, they had the chanceto ask for a hint, or search for help in the course library. If they wereunable to find the answer, or answered incorrectly, they would either see thescenario resolved properly, modeled by the course mentor character, or proceeddown an alternate path where consequences are shown. In either case, acognitive apprenticeship helps learners transfer these new skills over into thereal world.

Conversational writing style

While there may be some very sound reasonsfor using a “legalese” writing style, employees tend to cringe when they haveto read through the policies. Working in tandem with our legal and HR compliancedepartments, we were able to capture the meaning of the policies and translatethem into something that everyone could understand. Let me give you an example.

Here are two passages. One is taken fromthe Human Resource Policy Guide. The other is a passage taken from our course.See if you can guess which one is which.

Passage One:“You should not accept any money, property, gift, benefit, service, loan,credit, special discount, favor, entertainment or other items of value from anyperson with whom Allstate does business, with whom the company is seeking to dobusiness, or from any person seeking to do business with the company. The term“person” includes, but is not limited to, policyholders, claimants, financialinstitutions, or any business or professional firm or corporation.”

Passage Two:“The rule of thumb here is simple. Don’t accept gifts from a person/ supplierAllstate does business with or from someone who wants to do business withAllstate. An example of a situation you’d want to avoid would be to attend asporting event paid for by a potential supplier.”

If you haven’t guessed, the second passageis from our course. The tone of these courses needed to be conversational. Wewanted the tone to be conversational not only because the content needed to beeasier to understand, but also because we wanted our learners to feel immersedin the situations. We wanted them to feel as if they were being talked to, asif the characters in the course were their colleagues. By doing this we madethe experience more compelling, because the learner has been directly involvedin the action — and the outcomes.

Driving them to the tools

As much as we may not appreciate thestyle in which corporate policies are written, we felt that, once the learners understoodtheir meaning, that they would be excellent tools. A “Library” section was includedin each course that contained links to the actual policies and other resources.Learners were reminded that, as they ran into challenges or scenarios withinthe course, they should refer to the online guides.

The Library was an importantinstructional component. First, it helped learners to find success within thecourse — always a good thing when you’re doing simulations. Just as a gamedesigner would never throw players into a dangerous situation without a sword(or at least a way to get one), we didn’t want to frustrate our learners bythrowing them into simulations without some help. The Library also served toreinforce behavior that we hoped would transfer over after the course wascompleted. Simply put, we wanted employees to know they could go to the HRpolicies on our Intranet if and when they should run into future similarreal-life situations.

Gaming elements of a DEL approach

While the instructional elementswould lead learners to content retention, it was the gaming elements that wouldkeep learners tuned into the course. Briefly, here are the four gaming elementsincluded in the courses.

Scoring: Perhaps the greatest gaming elementof a

Figure 5 A learner (Melissa) loses 50 points for picking the wrong “Expert” in Level 2 of our Sexual Harassment/Non-Discrimination course.

Simplicity: Learners should be focused on thecontent, not the games. Games that seemed familiar and were easy to learn wereincluded in the design. One game, which was set in the employee cafeteria, was basedon the trivia games popular in many bars and restaurants. In those games,players compete against each other in answering timed, trivia style questions.The longer they take to answer a question, the less the question’s point valuebecomes. Our game is similar. Learners encounter various people in thecafeteria who would ask them multiple-choice style questions. But instead of atimed response, learners encounter a person on the screen who, in effect,“sells” them hints. For every hint the learner uses, the total possible pointvalue for that question goes down.

Relevancy: This wasn’t “Sexual Harassment SpaceInvaders” or “Ethics and Integrity Pac-Man.” Instead, games and gaming elementswere woven into the experience without our learners being overtly aware thatthey were engaging in a true game. Beyond the trivia-style games that tookplace in the cafeteria we also had match-game style games that took place in avideoconference room and “To Tell the Truth”-style games that took place in amanager’s office. The attempt here was to use games as a tool to keep learnersmotivated. Again, the focus was on learning, NOT on the game.

Higher Production Values: To engage our audience, a

Technology elements

Every effort was made to keep thingssimple in regards to development. We may have been going for a video game-like experience,but we absolutely did not have a video-game-like budget. Resources were limitedand we could not keep the client waiting. There was some upfront developmenttime as the interface and graphics for the first course were created. Buteverything was templated and designed to be repurposed. The development timefor other courses in the curriculum was then cut substantially. Not countingthe reviews and user tests, it took about two months to develop each courseutilizing (or not utilizing) three selected technology elements.

HTML-based: The programmer used Dreamweaver, anHTML editing tool, along with some small amount of java scripting, to designthis course. No plug-ins were needed to run these courses.

Impactful Graphics: Images and backgrounds were selectedthat pulled the learner into the experience. The images had a modern video-gamefeel to them, but did not include any animation. Basically, our graphic artistsimply took digital pictures of various locations around Allstate, and thendoctored them up in Photoshop to give them a video game “edge.” We just aseasily could have used the digital images in their original, un-doctored state.The goal, regardless of how we did it, was to give learners the impression thatthey were part of the scene. As far as hecharacters we had in the courses, they were just people from a clip-artlibrary. Our graphic artist simply found ones that had a range of expressionsand plopped them onto our digital backgrounds.

No Audio: In order to lower the bandwidthrequirements; no audio was used in these courses. This always seems to be anissue with many learners. For some people, they miss it when it’s not there.For others, it’s just a distraction. Surprisingly, as learner focus groups revealed,audio in our courses wasn’t missed.

From our user group sessions, we learnedthat users enjoyed the conversational tone of the courses, and found them easyto follow. What also seems to work in our courses is that per-screen wordcounts are kept to a minimum. If a block of text can’t fit into an on-screen speechbubble, it means we need to cut it down. By doing these simple things, theexperience becomes more enjoyable, and the audio isn’t missed.

Learner reactions to digital experientiallearning

Thorough user tests were included aspart of the design process since this curriculum contained several newelements. In total, about 60 learners actually took the courses while beingobserved. Afterwards, the HR Education team met with the participants and hadhour-long debrief sessions to collect their feedback.

The general reaction of the learnersto the

- Learners did not require elaborate“video game-quality” 3D animations. Static backgrounds seemed to capture theirattention and hold their interest.

- Learners didn’t require audio. Oneof our biggest worries was the trade-off we made in our decision to use high qualitygraphics over audio. Nearly all of the people in our tests stated that audiooften just “gets in the way” and that they didn’t miss it. They enjoyed theconversational tone of the text and liked the fact that reading, for each screen,was kept to a minimum.

- Scoring was a motivator. Justabout all of the participants expressed the opinion that it gave the courses amore competitive feel. Many people said that it made them want to re-read materialor look at the actual policy guides (which were accessible to learners througha “Library” section in the course) in order to get the answer “right” andreceive more points.

- Learners made connections that enabledretention. One of the most interesting things that I observed with ourparticipants was that many of them remembered the content because theyassociated it with a particular character in the course. One person said that acharacter that appeared in a cafeteria scene reminded her of a conversation shehad recently about a situation involving receiving gifts from vendors. Andbecause of what “Sue” (the character in the course) told her, she’d know how tohandle that situation in the future. Another user stated that she thought we“taped her lunchroom conversations because content matched up so well to manyof the concerns she was familiar with.

Conclusion

The time invested up front todevelop the

While a

References

Janz, Brian & Wetherbe James(1999). Motivating, Enhancing and Accelerating Organizational Learning:Improved Performance Through User-Engaging Systems. The

Oliver, Kevin (1999). Situated Cognition and Cognitive Apprenticeships. Retrieved September 12, 2002, from Virginia Tech, Educational Technologies Web site: https://www.edtech.vt.edu/edtech/id/models/powerpoint/cog.pdf

Postman, Neil (1995). The End of Education.

Sugrue, Brenda (2002). Practice Makes Performance. Retrieved September 13, 2002, from the American Society for Training and Development Web site: https://www.learningcircuits.org/2001/oct2001/sugrue.html (Editor’s Note: As of February 8, 2010, this article appears to have been removed from the Web.)