Jean Marrapodi, the chief learning architect at ApplestarProductions and senior eLearning designer at Illumina Interactive, has a wealthof experience as an educator. The eLearning Guild recognized her as a GuildMaster at Learning Solutions 2016 Conference & Expo. Jean has worked inspecial and elementary education at the primary level; adult education; highereducation; and adult education with a focus on working with low-literacyadults. She entered the eLearning arena at the very beginning of onlinetraining, working as a training marketing manager for CompUSA in the 1990s. Jeanhas excelled at bringing strategies and vision from primary and early childhoodeducation into her work with adult learners and corporate eLearning, and shelives by her motto: “It’s a great day for learning!”

I spoke with Jean recently about eLearning design for adultlearners who come into the training with a broad range of experience and knowledge.The interview has been trimmed for length and clarity; the first part of theinterview was published August 18.

Pamela S. Hogle: Youstarted out as a classroom educator and shifted to, not only not teaching kids,but online. What overlaps and what’s different with your current work, teachingadult learners online?

Jean Marrapodi: Myteaching background really did very little to prepare me for the change becauseit was all stand-up-and-deliver, pre-done curriculum. In the classroom, Itended to vary the curriculum that I was teaching and add a little bit moreenergy and creativity to it. I found myself in a very different world when Ibegan working in the corporate sector.

K-12 exposes children to a broad base of information, tokind of give them a foundation for life. Higher education continues thatexposure but takes a deep dive into a specialty area. Finally, we have earlychildhood, which is about discovery and exposure to the world. They want thekids to experience lots of things, and lots of it occurs through discovery. Itend to incorporate that early childhood thinking into the learning that Idevelop in the corporate world.

Corporate training is similar to education in that it has apredefined curriculum, but there is a need that is driving it, whethersomething is changing in the business, software, whatever, leadershipdevelopment—there is usually some driving force that says, “I need to providethis to my people.”

One of the other differences is the difference betweenandragogy and pedagogy. Pedagogy is the teaching of children, and andragogy isthe teaching of adults. Adults come to the classroom with a ton of backgroundexperiences that children don’t necessarily have, and so we have to expose [children]to things.

Adults, on the other hand, are more like Swiss cheese. Theyhave background, but there are definitely holes and gaps in their information.We work to provide remediation, in some cases, or, in the corporate setting, addingto the assumed foundation that they have.

PH: In a corporatesetting, or any setting with adults, you can’t assume that everyone has the samefoundation of knowledge, whether it is technical knowledge or knowledge in thespecific subject matter of the corporate environment.

JM: Exactly, andthat creates a challenge when you are teaching. We’d like to assume that theyknow certain elements of navigating a website, or saving a document, or cuttingand copying. But that’s not necessarily true. In the Millennial world inparticular, we have expectations that they know how to use the software—Wordand Excel and PowerPoint and all that—because they’re techno-literate intheory. In reality, they are mostly self-taught on those things; there’s a gap.

PH: So sometimesyou have to go back to the beginning, even with people who are digitallyliterate—in their own minds, anyway.

JM: Right. That’slooking for the hole in the Swiss cheese, and teaching to the hole rather thanteaching to the cheese.

PH: What advicewould you give to eLearning designers, particularly those who are relativenewcomers to eLearning and those who are designing for these diverse audiences?

JM: When you aredesigning a course, whatever it is, you need to be able to get it down to onesingle sentence: In the end, the learner needs to know ______ and be able to______.

If you can’t get to that point, you really haven’t definedthe point of the course well. And you should state that goal in the course. Atthe end of the course, you should say, “Hey, in this course, we learned how to ______.You should know how to ______. Do you think that you’ve gotten there?”

That question, that sentence, should solve a problem.Especially in the corporate world, there’s usually a need that they have fortraining, so your statement should be a solution to the problem. They don’tknow how to accurately do wire transfers? OK, in the end, they will know thelaws and steps to create a wire transfer and be able to effectively execute awire transfer.

And it may be with the aid of a job aid. There may be allsorts of conditions that we put around that, but you want to get to that onesingle sentence.

PH: Does thatsentence sometimes show you that a training course is not really the bestresponse?

JM: Yes. It suredoes. Because if there’s nothing that they are supposed to do in the end, howdo I measure that they’ve gotten what I’m trying to get across to them?

PH: Sometimesjust the job aid is the answer.

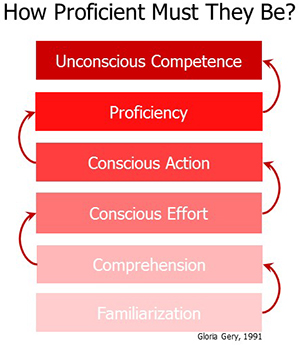

JM: Yes. And that’s OK. If that’sthe goal, then that’s OK. Gloria Gery had a wonderful chart [Figure 1] that sheused in her talks about how well you want the learner to know the knowledge. [Editor’s note: This chart began life as“The Four Stages for Learning Any New Skill.” It originated with Noel Burch, anemployee of Gordon Training International, in the 1970s. Gery and many otherspeakers and trainers have used it extensively over the years.] It startswith familiarity and goes up to unconscious competence. I need a person who’staking EMT training to be unconsciously competent with CPR. I need them to walkin and go. If I’m training an elementary school teacher on CPR, she might needto know it, but she can take action by thinking through the steps. She doesn’tneed to be unconsciously competent, so I don’t need to drive her to that point.I need her to know enough that, in the event something happens, she can take action.But the likelihood of her needing to take action doesn’t require her to beunconsciously competent. So we need to know how well we want them to learn.

Figure 1: Stages of learning (attributed to Noel Burch and Gordon TrainingInternational, c. 1970-1980)

When we’re doing new-hire training, we need them to have thebeginners’ level of stuff, where they’re going to need structure around whatthey’re doing. And that’s OK. A person who is an advanced learner, well, I’mexpecting them to know how to do some of this in their sleep. And some of thatcomes with practice, so at the end of training, it’s not always possible to beunconsciously competent.

PH: So not alltraining is going to get every learner to the same level. You really need toknow what’s appropriate for your situation, in addition to what the process isthat you’re teaching.

JM: Right. Andwhat’s the benchmark that makes it OK? In learning, we have this 80 percentmagic thing that allows learners to pass. They got 80 percent on the score, sonow they know business continuity. Really?

That’s not our goal. Our goal is that they know what to doin the event of an emergency, right? Not that they pass the test with 80percent. So we have to determine if what we have given them is actually gettingthem to the point we want them to be at.

PH: Is thereanything else you’d like to share with our readers?

JM:I’ve learned a lot; I have a master’s degree inonline learning and a PhD in adult education. But I learned a lot more in theyears I was in the trenches and connected with The eLearning Guild. It’s thebest place to learn practical nuts-and-bolts things. Leverage your personallearning community. Build a personal learning community, and the Guild isabsolutely the place to go.