In2006, the rebuilding Iraqi police recognized their need for a software systemto serve a wide range of functions, including providing a “back office”infrastructure. In Iraq, unlike in the United States, the Ministry of theInterior (MoI) hires and manages the police throughout the country, so thesystem deployment would be on a vast scale.

Thesoftware would address basic human resources (HR) issues, such as tracking andrecording who was hired, and how much pay they received. Additionally, thesystem would handle equipment inventory, and the collection and reporting ofcrime statistics for the entire country.

IdealInnovations, Inc (I-3) received the request to develop this software system tosupport the Iraqi Police. I-3 had already designed and developed severalsoftware systems for the Iraqi government. Several earlier projects in Iraqfailed due to inadequate user training and support. I-3 was determined not tomake those mistakes, so training was an important element from the beginning ofthe project.

I-3utilized its Texas-based software development and training teams in conjunctionwith project management located in Washington, D.C., and a “forward” groupsituated in Baghdad’s Green Zone. The forward group hired local Iraqis to workin various positions, and to do translations.

“Thebiggest challenge was that we didn’t know what the system was going to looklike, and we knew it was going to change a lot,” said Dr. Alex Kilpatrick, VicePresident of OCONUS (Outside Continental U.S.) Operations for Ideal Innovations.Because of the imminent deadlines, the teams needed to develop both thesoftware and the training nearly simultaneously, even though the requirementswere vague. This meant there would be a fair amount of rework. It also made itdifficult to schedule the training development, because of lag time thatoccurred when the training team had to wait for the software development teamto finish designing different modules of the application.

Theforward team in Iraq worked to collect requirements for the system from theclient, and communicated with the entire team via weekly conference calls ande-mail. I-3 also created a Microsoft SharePoint portal to keep allproject-related documents and resources in one place. The portal was aninstrumental collaboration tool that permitted the teams in different locationsand countries to share files. It also served as a back-up archive of the entireproject.

Inthe earliest design stages of the software, the training team identified, andstarted to address, some of the issues that would be problematic for trainingdevelopment. There wasn’t good information about the computer skills of thetarget audience, and there was conflicting information about theinfrastructure, such as how readily available computers and the Internet are tousers.

Therefore,the team decided to create training materials in both a paper-based,instructor-led format, as well as a self-paced e-Learning format fordistribution via CD or the Internet. Out of necessity, the team would createthe training in English, the native language of the entire development team,before translating it into Arabic and Kurdish for distribution to the learneraudience.

Arabic basics

Thereare 18 basic letters, augmented by dots, in the 28-letter Arabic alphabet.Written Arabic mostly leaves out vowels, except in religious texts or books forchildren and learners. Most Arabic written for adults assumes that readers willunderstand vowels from context.

Thefirst thing most people notice about the Arabic alphabet is that it proceedsfrom right to left. Numbers, however, go from left to right.

Atthe beginning of the project, none of the instructional designers or trainingdevelopers had experience with Arabic, or with working with any right-to-leftlanguages.

“We didn’t expect language to be an issue, but ithas been,” said Dr. Kilpatrick, “Getting Arabic on the screen wasn’t thatdifficult. We originally tried to translate isolated text, but we discovered inthe QA (Quality Assurance) phase that subtlety and meaning were lost. This wastrue for both the software user interface and for the training modules. Wetranslated strings of text correctly, but once the testers started to use theintegrated application, we discovered that many of the error messages and instructionsdidn’t make sense in the context of the application. Also, the field validationwas different for English and Arabic, and the development team spentunanticipated amounts of time writing code for two different sets of validationrules. Having the translators working with both the application and thetraining for the application together made both the application and thetraining better.”

“Flipping” the interface

Theteam had experience in designing and developing e-Learning in multiplelanguages, including work with the most-common romance languages. In earlierprojects, an outsourced company usually provided the translations. Previousexperience taught the team that translating training content was never astraightforward process, and that it was important to include client memberswho spoke the target language in the selection of translation companies.

Inthe normal process, the teams developed training in English, and then extractedthe content into a table the translators could use. One column had the Englishtext, broken up as needed, and the translation company put the translated textinto a second column. A script automatically re-populated the content into anew instance of the interface to create the new version. (See Figure 1.)

Figure 1 The development team created the training in English first, for later translation.

Forthis project, we had to reverse the entire interface to display from right toleft. The menu bar started at the upper right corner of the window, and the“next” button was on the left side of the navigation bar.

Interface design and graphicselection

Becausethe English version of the training was for development purposes only, the teambuilt the interface in both languages with a right-to-left design. (See Figure2.) This was a bit awkward at first for the training team, but made developingthe Arabic version later on much easier.

Figure 2 The interface organized content from right to left, regardless of language.

Theteam created several interface prototypes for review by the target audience.From previous projects, I-3 had already learned about some Iraqi preferences;in general, Iraquis prefer interfaces and styles far more ornate than thosenormally seen in business applications. The interface went through severalrevisions, with minor adjustments made along the way. The design of thetraining interface influenced the design of the software interface; afterseeing early prototypes of the computer-based training, the developers wentback and put more effort into designing the look of the software.

Graphical elements

Inthe analysis phase, the team received conflicting information on the educationlevel of the learner audience. While the population in general is well educatedand computer-literate, this project was to be released across the entirecountry. (See Figure 3.)The team wasn’t certain of the education level andcomputer literacy levels in more remote areas. Under the assumption that thetranslations would not be perfect, they designed graphic elements to stronglysupport the content.

Figure 3 Uncertainty about the quality of translation led to creation of graphic elements that would strongly support the content.

Fora diverse, nationally-dispersed population, creating appropriate graphicsprovided new challenges. Generic blue featureless figures originallyrepresented people in all of the training graphics. This changed with the needto differentiate between types of users of the system; the system was for theIraqi Police, and I-3 needed to differentiate between police officers andrecruits. (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4 Graphics had to differentiate between different types of users of the system, for example, between police officers and recruits.

Later,the team changed the graphics again to reflect an appropriate representation ofaudience types. Even more so than in the United States, in Iraq it is importantto have both male and female police officers, because only men can search andinterview men, and only women can search and interview women. Clearly, thegraphics needed both male and female figures, and a later change included the additionof skirts and head scarves, or hijab, for some of the female figures. (SeeFigure 5.)

Figure 5 Graphics needed to represent individuals in culturally appropriate ways.

Photographsaugmented the drawings, and some portions used video. It was easy to obtainphotographs of the equipment, but for the video elements, it was important thatthe people in the video be consistent with our target audience.

Security considerations forgraphics

Traditionally,the biggest concern for training graphics was getting proper releases from thesubjects who were photographed or videotaped. In Iraq, this presented a newconcern. Iraqis working as policemen and policewomen, as well as theirfamilies, faced a significant danger if they were broadly identified as beingpart of the police force. Finding any Iraqis who were willing to serve asmodels for the training was impossible.

Notwanting to use American models, the team tried to use models from otherMiddle-Eastern countries, but test subjects immediately identified them as“non-Iraqi.” Furthermore, in Arabic culture, people generally consider it rudeto photograph any female.

Usingcaricature type representations of the Iraqi police that were sometimes staticand sometimes animated proved to be the best solution. We could use real modelsin cases where their faces did not show. This solution turned out to have someunexpected benefits.

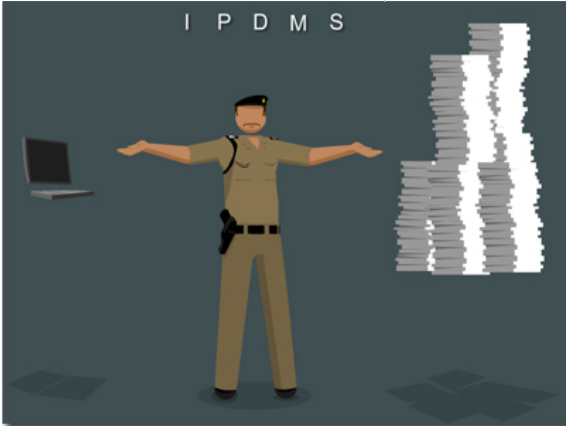

First,the Iraqi police uniform was undergoing rapid changes at the time the teamswere developing the training. By using cartoon-style graphics, the trainingdepicted a general uniform idea, not any specific uniform style. (See Figure6.) This eliminated any problems reconciling differences between BaghdadMinistry of Interior police uniforms and Kurdish Regional Government policeuniforms. Furthermore, because the cartoon figures had no real faces, therewere no issues related to representing females.

Figure 6 Cartoon style graphics solved a number of problems related to uniform details.

Thecartoon figures also provided more flexibility in presentation. Instead ofhaving to keep going back to Iraq to get a different pose for a model, we couldjust change the graphic.

Timing considerations for audio

Thecomputer-based training modules consisted of a mixture of video, flashanimation, and static images. By not relying entirely on video, the audiorecording process was much easier. With video, the timing of the video sequencelimits the length and timing of the audio. Because we relied mostly on Flashanimation, the Arabic speakers were not concerned with limiting theirtranslation and recordings to a specific time period. They could easily manipulatethe animation to match the timing of the Arabic audio. Moreover, the animatordid not need to understand the Arabic audio files because their segmentationmatched each scene in the training module. The e-Learning included Flashelements with embedded audio. In order to create the Flash with Arabic text andaudio, translation and recording of the content had to be in both English andArabic.

Thefirst audio recording was in English in a draft form, using neitherprofessional voice talent nor a recording studio. (See Figure 7.) It was onlyfor the working version of the program. The English audio helped the developerstime the Flash interactions.

Figure 7 Making the first recording in English helped developers time Flash interactions.

Thedevelopers broke the content into chunks based on the animation timing. The translatorsalso worked with the text. In this way, the team could redevelop the animationsusing Arabic text and audio while maintaining proper timing. The developmentteam could not read or understand spoken Arabic, so a sound QA process wascritical for project success.

I-3used a mix of male and female voices for audio. The team opted for a mixinstead of a single narrator because of uncertain availability of voice talent.They knew they would have to do a lot of re-work, and a single, originalnarrator might not always be available. By intentionally using a mix of voices,I-3 ensured that the audience would not be surprised or distracted when thevoice of a narrator changed.

Initially,developers received advice that both male and female Iraqis respond better to amale voice. However, after further investigation, it became clear that this wasfar from universally true. Using a mix of male and female voices increases thetraining’s appeal to different audiences, and keeps the learners engaged withdifferent voices as well.

Lost in translation

Onthe other side of the world, the translating team had varying degrees ofexperience in translating technical and training content. One team member wasfluent in both English and Arabic and was a skilled translator; others had lessexperience, but were more familiar with technical vocabulary. For example, inone early version, the team discovered that the word “training” had beentranslated using an Arabic word more appropriate to “training an animal” asopposed to “learning.” The team adjusted the translation process to include astep for having a second Arabic-speaking native double-check each translation.This turns out to be an essential and critical step, especially in the casewhere the training development team does not speak the language of the deployedtraining system. There is little reason to have an instructional designer takethe time to carefully craft learning interventions if the nuances of meaningare lost because of poor translations.

Anotheradded benefit from having a central QA person who reviews all the translationis that this person will experience the training module in its entirety, andwill look for consistency in wording and style in various sections that, due tothe time crunch, were translated separately or by multiple people.

Weused the same translators to translate the text, to translate the userinterfaces, and to review the audio, animation, and video in the final andcompleted training module.

Integration

Adobehinted that Flash would support bidirectional languages like Arabic in thelatest version, but the support wasn’t available in time for this project. As afirst approach, the development team searched the Internet to find some sort ofcode that a fellow Flash-user might have written that would parse through thetext and invert characters so that Arabic would display properly. This approachdidn’t cost any money, but it didn’t yield perfect results.

Thedevelopers didn’t know enough about Arabic to write such a function themselves,and the functions they found didn’t always display mixed strings (with Arabic,English, and punctuation marks) correctly. They adapted it to fix one obviousproblem, but the approach was still not bullet proof.

Anotherdrawback was that the team could not embed fonts in the Flash movie. They couldonly get the code to work properly by using the default sans-serif font on theend user’s computer, and this meant that they couldn’t apply special filters tothe text (e.g. drop shadows) or get text to fade in and out.

Morerecently, the team purchased a component that seems to be well coded and wellsupported: Flaraby (https://www.arabicode.com/flaraby/flash_arabic_support.php ).This component permits the embedding of eitherthe “Traditional Arabic” or “Andalus” fonts, and seems to handle the varioustext mixtures without error. It’s trickier to use (you must use scripting toimplement it), but it enables normal visual effects and doesn’t displayparentheses in the wrong places or facing the wrong direction (left to rightversus right to left).

Anotherintegration challenge is that Arabic fonts display at about two sizes smallerthan English fonts. When we increased the font size so that the Arabic usercould better read the text, we had to check for possible changes in line breaksand make sure all text was still visible.

Summary

Thelessons we learned from this interesting and challenging experience were:

- Keep an open mind about the culture, languageintricacies, the technological challenges and advances for the language, designpreferences, talent pool available and expectations of your target audience.Working with a new culture or language will be a learning experience, and it isimportant to set up your team so that it can adapt to the cultural variations –some of which you may discover while the project is in progress.

- If you don’t already do this, use a portal or afile sharing mechanism that allows you to collaborate with all teams in theirvarious locations, and include the client if required. We used a SharePointportal because some of our government clients did not have FTP access, whereaseveryone has access to the Internet via a Web browser. We also found regular conferencecalls instrumental in collaboration.

- Use varying training media (CD, Internet, paper,instructor-led courses, etc.), and base you choice on the technologiesavailable to the end-users. The infrastructure in other countries is not alwaysthe same as in the US. Some countries have a better infrastructure, but in mostcases the infrastructure is either similar to the U.S., or worse.

- One of our advantages is that our softwaredevelopers had worked with the Arabic language before, even though the trainingteam had not. It’s good to have technical persons accessible who understand thetechnical challenges of working with the language. It may also be useful toprovide the team with a brief understanding of the cultural and languagedifferences. Such information is available online, but a linguist or native ofthe language who is working with your team will be able to provide a betterexplanation.

- Assign a primary translation QA person who willoversee all of the work. This person’s role is to understand the full trainingmodule, and make sure the translations are in context. This person will alsohelp unify the terminology and style of the training course. Repetition is oneimportant learning technique, and the translations will not have the sameeffect if different synonyms are used to relay any deliberately-repeatedinformation.

- If your development team does not speak thelanguage, if possible use a dynamic training solution that allows them to flipback and forth between English and the target language.

- Show your work at different milestones to thetranslation team, and to the client if that is possible. It’s important toobtain feedback about critical issues early on.

- Research technical issues that arise with thelanguage you are working with. Others out there may have encountered the sameissues and have found useful work -arounds.

Developing trainingmodules for a client in a foreign culture, who speaks a language different fromyour own, can be very challenging. However, in our global economy, where theworld is constantly shrinking due to the advances in technology, it can be arewarding experience, expanding the expertise of the team and expanding thehorizons of each individual team member.