If you are like us, you often have business managers approachthe training department with requests similar to these:

- “Weneed a two-hour workshop on team building.”

- “Ineed my employees to know XYZ so our [desired output] will get back on track.”

Nowadays, if you are the designated developer for ad hoconline training, such requests could not only presume the content, but alsoonline delivery.

Notice what’s being asked—and not asked—in both requests: theclient has already identified the solution, and that solution is based on whatthe client thinks the employees need to know.What’s not being addressed, at leastat this point, is the desired performance, or what employees need to do.

A typical request

Managers,executives, and other clients often come to the training department with the solution to a perceived problem alreadyin mind. This is not surprising, since such folks are action oriented. But thesepresuppositions can derail the instructional design process if a trulyeffective solution is what the client desires. Even if the request is not tosolve a problem, but rather to introduce a procedural or systems change, it istempting for such clients to build a laundry list that they believe the course shouldor must address. Further, these lists may include things that are already available atthe worksite in the form of written procedures, manuals, or today, inelectronic form as support systems.

While responding to the laundry-list approach may temporarilysatisfy the client, it may do little to solve the underlying performanceproblem or successfully introduce a change. And it becomes quite inefficient iftopics are added in a laundry-list style without describing the behavior neededfor successful performance or assessing the time it takes to address them intraining.

Early inour careers, we found ourselves trying to explain ISD to clients. We wanted toemphasize the importance of a needs assessment, explain some key designelements, and discuss the nuances of implementing and evaluating the training. Thiswas our mistake.

Managersand executives are action oriented. Solving problems is what they do—quickly. Theydon’t want to hear about the nuances of instructional design or why we need tospend the time parsing a task or job before designing the training for it. Typically,these clients will discuss their laundry list, the number of people they wanttrained, and the timeline or schedule. This excludes the wisdom of focusing onemployees’ performance. What is often missing in such conversations is thedialogue that seeks:

- Potential explanationsfor current performance

- The desired performanceoutcome(s)

- The level ofquality expected, compared to current performance

Knowing vs. doing

In our experience, most business managers don’treally understand how training and instructional design work, nor should theyat the level of an ISD (instructional systems design) professional. Althoughthey are adept at managing the business, some clients may not intuitivelyunderstand that by focusing on what they need their employees to do vs. what they think they should know, they will move much moreefficiently to the solution they’re after.

In the past, when we tried to explain why the focusshould be on performance and not “knowing” certain information, it was hard tohold the client’s attention long enough to get to the punch line.

According to J.E. Hunter, clients often make a very common assumption,that if employees know certain things, they can and will do them. Researchevidence as well as ISD practice demonstrates that knowing supports doing butas G.M. Alliger and E.A. Janak note, knowledge alone does not ensure thatemployees will do anything differently (see References).

Let’s talk about performance

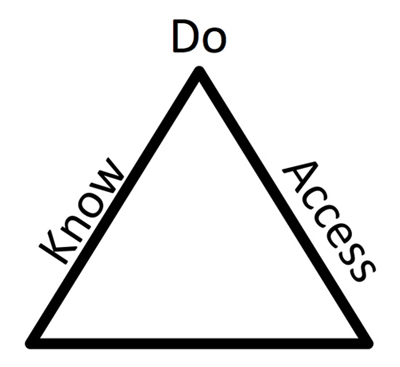

Sohow do we direct the conversation to performance and not knowledge? Enterthe Do—Know—Access triangle(Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Do—Know—AccessTriangle

Nearly 20 years ago Mark Teachout (one of the authors of thisarticle) was in a meeting with a senior executive, an open-minded new client, whowas requesting training. After listening intently to the client’s descriptionof his department and challenges (this also included the laundry list), Markdrew the Do—Know—Access triangle on a napkin to facilitate what became a veryproductive discussion. Importantly, this simple diagram helped to shift theconversation and differentiate these three concepts, ultimately leading to avery successful client relationship.

Teachout and Hall (see References) first described the use ofthis triangle as a means of focusing the conversation on these three concepts,away from the old conversations described above.

Firstwe focus clients on what employees need to be able to do to be successful onthe job. This avoids premature knowledge-only solutions that are not linked tothe specific performance changes desired. Once we gain agreement with theclient on what employees must do, we can then determine what they need to knowversus what they need to access through job aids or performance support systemsin order to do the job. These distinctions help to overcome the expectationthat a list of topics will be taught, independent of performance expectations. Again,there is often an expectation on the part of clients that simply impartingknowledge to the individual will change his or her on-the-job behavior andimprove performance. Usually, there is a need to focus and refocus theattention of others on the desired performance and business results expectedfrom the training program. This simple yet powerful approach helps to manageclient expectations and provide a sharper focus on the desired performanceexpected as a result of the training while avoiding a common pitfall offocusing on knowledge only. It also helps to avoid including knowledge-basedinstruction that is available in performance support systems.

Importantly,this shifts the conversation to what employees need to do, rather than what they need to know. Second, it highlights the potential availability ofinformation already available at the worksite and thus, perhaps not necessaryto teach. That is, it distinguishes support information that can be accessed on the job from actual trainingthat is necessary.

The key that opens the door (to more efficient needs assessment)

We have used this approachfor more than a decade in our roles as ISD professionals and consultants. Wehave found it to be like a key opening a door. Clients are unlikely to beinterested in the nuances of ISD, but we have seen them immediately grasp this diagramwith the action word DO at the apex. We have foundthat this simple approach fast-forwards conversations that were previouslydrawn out, and avoids some potential mistakes by both parties. When you showthe diagram and use the question, “What exactly is it your employees needto do?” it adds focus and helps you and your client to get to the point.Then when you explain that not everything needs to be trained or memorized orinternalized—that’s where the knowand access come in. Time after timewe have seen the light bulbs coming on just a few sentences into theconversation. When this happens, the ISD professional gains credibility andbuilds trust with the client.

Involve the managers in design

The Do—Know—Access triangle also engages managers in the designof the training. When they realize that the less costly and practical option isto trim unnecessary knowledge and to accessinformation at the worksite in the form of a job aid or electronic supportversus learning (knowing) during a training course, then they become fullyengaged. They quickly see that the combination of training and supportmechanisms can be a more efficient use of time and resources, while maintainingthe focus on doing the job correctly.

An investigative tool

In fact, the second author often uses the followingapproach to see what people are currently accessing. When he goes to a managerto begin a training intervention he likes to stroll through the corridor andsee what kind of sticky notes or crib sheets people have on their computer or cubiclewall, because these memory-joggers often indicateinformation to which they need ready access. This preview may or may not beuseful in the first meeting, but it will certainly come in handy when leadingthe manager through the Do—Know—Access conversation.

On-boarding struggle?

A final note: New employee orientation (NEO)is sometimes a good example of the laundry list- or wants-based approach. Inseveral companies where we have worked or consulted, executives often want tosolve current operational issues by addressing them in new employeeorientation. The conversation often goes something like this: “We need to makesure everyone knows about this—let’s be sure to add it to NEO.” And so the NEO agenda steadily grows untilsomeone finally feels that new employees are spending too much time in NEO whenthey’re needed on the job.

Focus on performance

What we suggest instead, and what we have seen donemarvelously in some organizations, is to—you guessed it—focus on performanceand not on a revolving door of guest speakers, each of whom gives a PowerPointpresentation on their topic of expertise. Assuming most new employees will bereceiving some level of training for their actual job, what do they really needto learn in NEO? (Keep in mind that if NEO is nothing but verbal presentationsthen the retention rate for that information is probably low, anyway.) That is,what will new employees need to dotheir first few days in this organization?

One thing is to help them confirm they made theright choice in coming to work here. Another is to indoctrinate them in thecorporate culture, hopefully by example rather than by telling them what it is.Each employee will be making judgments as they settle into their jobs. Youcan’t possibly predict all the situations they’ll encounter, so it is vitalthat they learn and buy into the overarching culture, which in turn will guidethem when they hit those gray areas. (And, of course, they will be told tocheck with their manager when in doubt.)

Useful and effective

So the Do—Know—Access triangle has been a useful tool fordesigning new employee orientation. We have seen some cases where, in light ofthe too-common fire-hose treatment in the first few days at work, employees geta brief personal indoctrination and then complete the rest of their NEO inshort, well-timed online modules that are spread over a few weeks or evenmonths. This way the new employees have some time to gain some context in orderto better assimilate some of the things they need to learn.

To summarize, we have found the simplicity of the Do—Know—Accesstriangle has a double benefit. First, it focuses on important distinctions thatbecome almost immediately intuitive for the client. We have seen the client’stendency to focus on a laundry list of topics evaporate. Second, because thattendency evaporates, it enables us to devise prudent solutions much morequickly and effectively, and with the client on board as a partner. Now whatcould be better than that?

References

Alliger, G.M., and E.A. Janak. “Kirkpatrick’s Levels of Criteria: Thirty YearsLater.”Personnel Psychology, Vol. 42, No. 2. 1989.

Hunter, J.E. “CognitiveAbility, Cognitive Aptitudes, Job Knowledge, and Job Performance.” Journal of Vocational Behavior, Vol. 29, No. 3.December 1986.

Teachout,M.S. and C. Hall. “Implementing Training: Some Practical Guidelines.”In J. W. Hedge and E.D. Pulakos (eds.),Implementing Organizational Interventions: Steps, Processes, and Best Practices.San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2002.