Theodore Roosevelt is oft quoted as saying that “Nothing worthhaving was ever achieved without effort.” This month I am going to extend lastmonth’s discussion of how difficulties and challenges enhance the learner’sability to retain information.

To get started, I have a question for you. True or false? “Thebest training programs are easy for the student and produce rapid learning.” Mosttrainers immediately agree with this statement. After all, if the training iseasy the learner is happy, and if it produces rapid results the organization ishappy. It must be great, right?

Maybe. But maybe not.

Researchers from neuroscience, psychology, education, and evenkinesiology have studied the question from many perspectives and have reachedthe surprising conclusion that infusing training with strategic difficultiesand challenges dramatically improves the learner’s long-term retention. I’dlike to illustrate this body of research by describing the creative work of mycolleague Dr. Kellie Green-Hall at the California Polytechnic State University.

Take me out to the ball game

Dr. Green-Hall is an avid baseball fan and she wanted todevelop a training methodology that would help her college baseball team to hitthe ball more effectively. Before I explain more, let me provide a bit ofbackground to those who know nothing about the sport. A college baseballpitcher throws a ball at about 80 miles an hour and, within less than half asecond, a batter has to judge its vector and attempt to hit the ball. It issaid to be one of the most difficult challenges in all of sports. The task isespecially difficult because in addition to throwing the ball fast, a skilledpitcher can also make the ball curve, rise, drop, slide, screw, or have an erratic,unpredictable motion.

Green-Hall watched her team and she noted that, during battingpractice sessions, the pitcher would routinely notify the batter that he wasgoing to throw a series of a particular sort of pitch, so that the batter coulddevelop his skills at hitting this sort of pitch. Green-Hall wondered about thewisdom of this. She wondered, “If I want to teach someone to become a betterhitter, should I train him with one type of pitch at a time or am I better offmixing it up, throwing some random series of fastballs, curves, and droppers?”

The consensus among coaches is that batters do better if youteach them to hit one type of pitch at a time. Green-Hall was skeptical,however, and she convinced the coach to put his beliefs to the test. As aresult, each day, the players were permitted 45 additional pitches of battingpractice. Half of the players received 45 pitches grouped into three blocks:fifteen fastballs, fifteen changeups, and fifteen curveballs. These playersquickly adapted to each type of pitch and hit them easily.

The other players received 45 pitches presented in a randomorder. They too received fifteen fastballs, fifteen changeups, and fifteencurveballs, but on any particular pitch, they did not know which one to expect.These players found this task more difficult, they learned more slowly, andthey hit the ball less consistently.

This initial result suggests that the coaches were right andit supports the more general notion that “the best training programs are easyfor the student and produce rapid learning.”

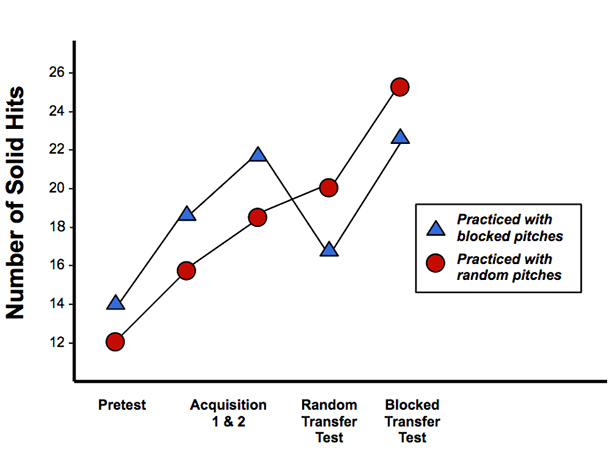

But there is the more to the Cal Poly study. After some days,the researchers did a follow up assessment and here the results were quitedifferent. During the follow up, the players who practiced with random pitchesactually did markedly better than the players who received the pitches groupedtogether. In fact, the random batters did better during the assessment phase,whether these pitches were delivered in blocks or randomly (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The playerswho practiced with the pitches delivered in blocks performed significantlybetter during the training periods. However, the players who practiced with themore difficult, randomly-delivered pitches did significantly better during thepost-training tests.

The finding is actually quite remarkable. The group of playerswho learned more slowly, and who hit the ball less consistently duringtraining, actually did better when it counted, during the assessment.

Why is difficult better?

The players in the block-training condition knew what toexpect on every pitch. As a result, they quickly adapted to the repetitivechallenge of hitting a curve ball and their performance during the trainingphase improved. But they were practicing a simple repetitive action (which is aform of massed practice); this relies only on retrieving information from short-termmemory. Such training does not require accessing long-term memory and, as aresult, little improvement occurs. In contrast, the players in the random-trainingcondition did not know what to expect on any pitch. Their task was more complex(it is a form of spaced training) and it required the hitter to constantly makereference to long-term memory. As a result, their performance during theacquisition phase was only mediocre. But in the background, this slow learningwas producing steady and long lasting learning. And in turn, they were able todemonstrate the long-term benefits of this learning during the assessmentphase.

These results illustrate a general phenomenon we seethroughout the learning literature: the training techniques that produce thebest long-term effects:

- Incorporate strategic difficulties,

- Require the learner to exert more effort, and

- Often slow down learning.

This lesson has clear implications when we are teachingemployees a physical skill in a manufacturing setting, but the same logicapplies when we are teaching soft skills like leadership. It is important tochallenge learners. Oblige them to process your material in a deep and personalway. And slow them down so that they need to spend more time interacting withyour material.

People may resist

Training that requires effortful processing produces betterlong-term learning, but this does not mean that learners are going to like it.In fact, many learners are likely to resist effortful processing. Bydefinition, effortful processing requires more hard work, and as Thomas Edisonused to say “A man will resort to almost any expedient to avoid the real laborof thinking.” As a result, implementing a more rigorous training program willrequire you to reassure your learners, and your supervisor, that the harderwork is justified because it will produce greater long-term benefits.

The illusion of mastery

Green-Hall’s experiment also makes the important point thattrainers are often misled when a learner appears to have mastered material. Atrainer may assume that, just because a learner is able to answer questionsfollowing training, they have somehow mastered the material. Their ability toanswer questions after training, however, demonstrates only that the learner isable to retrieve information out of their short-term memory and it tells usnothing about whether this information is being consolidated in their long-termmemory.

All of us want to provide training that is popular, easy, andthat produces immediate results. But keep in mind that people (such as baseballcoaches) often misunderstand how to produce real learning. Furthermore, ourultimate goal is to produce long-term retention and behavior change in theworkplace. When we want to determine “the best training method,” we should not be counting (a) whetherlearners like our training, (b) how easily they learn, or even (c) howquickly they master a task. Instead, your real measure of success needs to behow well your learners retain the knowledge and then apply it in the workplace.To maximize this retention and transfer, you need to add desirable difficultiesinto your training routines.

There are several ways to make training and retrieval morechallenging, and next month we will look at how to incorporate “desirabledifficulties” such as spacing, interleaving, and contextual variation. We willalso examine difficulties that are gratuitous and that can actually reduce long-termretention.

Digging deeper

If you would like to have your memory of this article boosted,send an email to [email protected].You will automatically receive a series of boosters on this series of articles.The boosters take only seconds to complete, and they will profoundly increase your ability to recall thecontent of these article.

The Thomas Edison quote has become part of the loresurrounding America’s greatest inventor. However, the quote actually has a longheritage and you should check out this fascinating article on the history of the quote.

I also encourage you to read the actual research article aboutthe Cal Poly baseball team. The entire article, “Contextual Interference Effects with Skilled Baseball Players,” is available online.

From the Editor: Much more Brain Science atDevLearn!

ProfessorArt Kohn will present a Pre-conference Certificate Program, “Applying Brain Science to Improve Training and Change Behavior,” on Tuesday, October 28, at DevLearn in Las Vegas. Explore thecore principles that will help you understand how the brain controls learningand behavior. Discover how to leverage neurological principles to createsustainable behavior change, both within the individual and your entireorganization!

In addition, Art willpresent “Building Online Training to Promote Learning Transfer and Behavior Change,” Session 602, on Thursdayafternoon, October 30. Learn how you can use eLearning technologies to maximizelearning transfer and positive behavior change. Discover the three myths ofeLearning and learn why overcoming these myths is critical in improvinglearning transfer. Discuss how interactive eLearning, simulations, andsocial-learning environments can work together to sustain learning transfer. Youwill leave this session with a concise and useful overview of eLearningstrategies that increase learning transfer.