Neuroscience has learned a lot about the way that the brainprocesses visual information. During the last twenty years, advertisers havelearned to exploit these insights to increase their appeal to the consumer. Youcan like or dislike these techniques. You can find them annoying or evenexploitive. And maybe they are. But they are also effective at grabbing ourattention and we in the learning community should be aware of them.

This is certainly my most biological article so far, but stickwith me. I think it will give you some cool insights into your visual world andinto the world of teaching and learning.

To get started, we need to explore our sensory system.Conventional wisdom tells us that we have five sensory systems: Vision,hearing, tactile (touch), olfaction (smell), and taste. In fact, however, wehave many more sensory systems, including heat, cold, proprioception (the senseof the relative position of parts of the body), the vestibular sense (anawareness of body balance and movement), among others. Furthermore, researchershave begun to realize that some senses consist of a combination of two or moresensory systems that get fused together by our experience. For example, ourexperience of vision is the result of two distinct systems that operateconcurrently but independently.

The “where system” vs. the “what system”

The two visual systems are known as the “where visual system”and the “what visual system.” These two sensory systems both operate on visualinputs, but they are located in different areas of the brain and they are asdifferent from each other as the sense of sound is different from the sense oftouch.

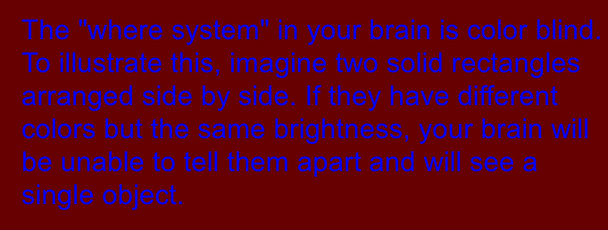

The “where” system was the first to evolve and it is presentin all mammals. The “where” system helps organisms with the everyday challengesof survival. This system processes low-acuity images (in computer language itworks with a low-resolution image) but it processes that information veryquickly. In turn, the “where” system provides animals with motion perception,depth perception, and spatial organization (i.e., the location of objectsrelative to each other). Interestingly, the “where” system is utterly colorblind; it sees the world only in black and white.

The “what” system, on the other hand, evolved much later andit exists as a second visual system but only in primates. The “what” systemhelps advanced organisms to critically analyze stimuli and make more sophisticateddecisions. The “what” system processes high-acuity images (that is, it workswith a high-resolution image) but it processes visual information very slowly.This “what” system is less reflexive and provides animals with advanced abilityto recognize objects. Hence it got its name, the “what system,” since it tellsus what things are. In contrast to the “where” system, the “what” system seesthe world in living color (Table 1).

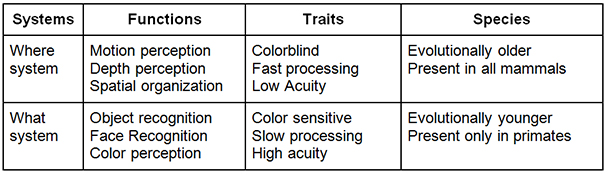

Table 1: The two visual systems compared

Table 1: The two visual systems compared

What and where in fine art

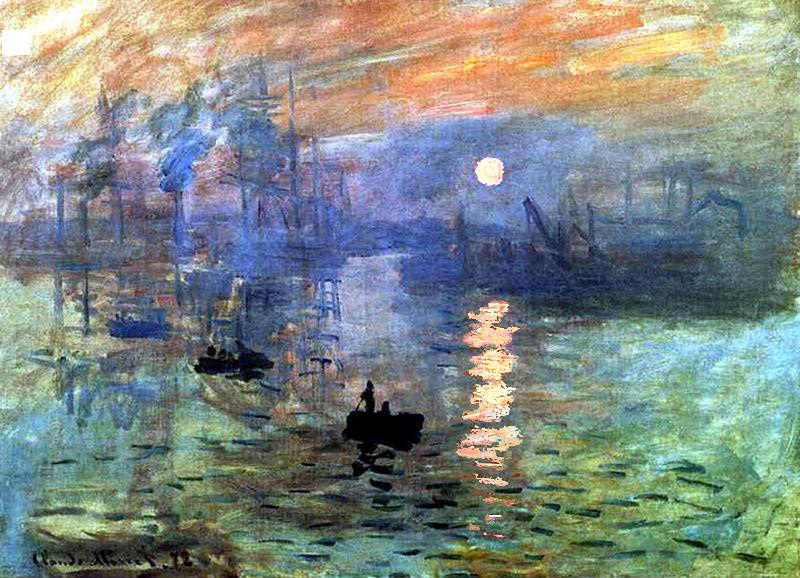

Let’s have a look at the two systems in action. Take a look atFigure 1, the painting Impression,Sunrise by Claude Monet (1872). In this original version, the setting sunand its reflection on the water somehow seem to vibrate against the background.They seem to move behind the clouds and to ripple along with the rise and fallof the water.

Figure 1: Impression, Sunrise, by Claude Monet

Figure 1: Impression, Sunrise, by Claude Monet

How does this happen? Why does it feel so dynamic? The answerhas to do with the way that the “where” and “what” systems are processing theinformation.

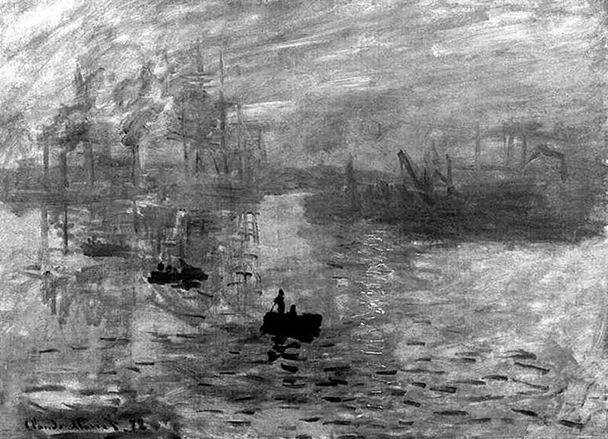

To most people, the sun seems brighter and more intense thananything around it. But in fact, the sun is exactly the same brightness as thesurrounding images. To prove it, I created this image in Photoshop using theimage>adjustments>desaturation tool (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Impression, Sunrisedesaturated.

Figure 2: Impression, Sunrisedesaturated.

In this black and white image, I removed the colors, butretained the differences in brightness. Note that the sun all but disappearsbecause it is exactly the same brightness as the surrounding objects. Importantly,this is exactly what the “where” system of your brain sees when it looks atthis picture. It is unable to see the sun as a distinct object because, fromits color-blind perception, the sun is exactly the same brightness as thesurrounding stimuli.

In contrast, the “what” system, which is sensitive to colors,immediately recognizes that there is a bright orange object in the picture, andit identifies what that object is,namely, the sun and its reflection on the water.

Why does the sun shimmer?

So why does the sun seem to shimmer? The answer is that your “what”system tells you that there is a sun within the painting. But your “where”system, the part of the brain responsible for position and movement, cannot seeit and therefore you have difficulty in determining exactly where the objectshould appear in the visual space. As you gaze at the image, your brain makes aseries of guesses about its position, and this creates the eerie sense ofmovement.

For those who desire a bit more proof, I offer one more image(Figure 3). In this I used Photoshop to brighten the sun and its reflection sothey are now brighter than the background. In this third image, the “where”system can easily see the brighter sun as a distinct object, and as a result itcan determine its exact location. The result: the eerie movement disappears.

Figure 3: Impression, Sunrisewith no motion

Figure 3: Impression, Sunrisewith no motion

I am not suggestingthat Monet understood the physiology of the brain in the way you do. Instead,he probably just did a series of trial and errors until he discovered theillusory movement. It was not until the amazing work of Margaret Livingston andNobel laureate David Hubel that that we understood the underlying biology ofthe phenomena.

Exploiting the “where” system

Now that we do understand how the where and what systems worktogether, some people are able to exploit this process for their own commercialgood. Consider the following text samples (Figures 4 and 5). Which is hardestto read?

Figure 4: Is this easy to read?

Figure 4: Is this easy to read?

Figure 5: Is this easy to read?

Figure 5: Is this easy to read?

Almost everyone finds the second image much harder to read. Thereason is that in the bottom image, the words and background are equallybright, so your colorblind “where” system does not see the words. As a result,your “what” system is forced to guess the exact location of the letters inspace, and hence the letters seem to jump around on the page.

Commercial artists routinely use images like this to draw ourattention to their advertisements. But these facts also have implications fortrainers and instructional designers as well. The fact that the second image isharder to read means that people have to take longer and work harder tocomprehend the words. And you know what? An abundance of evidence shows thatwhen people work harder and take longer studying material, they end upremembering it better. That’s right, forcing people to slow down and workharder will actually increase comprehension, retention, and transfer.

This deserves much more discussion and analysis. Next month wewill explore how you can apply this principle to your daily training.

Digging deeper

If you want to know more about this topic, the best textbookis Sensation and Perception, 8thedition published by Cengage Learning. It includes a CD-ROM with lots ofinsightful activities. If you want to explore the role of vision in the finearts, you must read Vision and Art, The Biologyof Seeing by Margaret Livingstone. Even if you do not understand her everypoint, it is a pleasure to read and after reading it, you will not see yourworld the same way again. I have never met Dr. Livingston, but I am a huge fanof her work!

If you would like to have your memory of this articleboosted, send an email to [email protected].You will automatically receive a series of boosters on this series of articles.The boosters take only seconds to complete, and they will profoundly increase your ability to recall thecontent of these articles.

References

Goldstein, E. Bruce. Sensationand Perception (with Virtual Lab Manual CD-ROM) (8th ed.). Independence,KY: Cengage Learning (Wadsworth Publishing), 2009.

Livingstone, Margaret and David Hubel. Vision and Art: The Biology of Seeing (updatedand expanded edition). New York: Abrams, 2014.

From the Editor: Want more?

JoinArt on Tuesday, October 28 at DevLearn in Las Vegas for hisPre-conference Certificate Program, “Applying Brain Science to Improve Training and Change Behavior.” Explore the core principles that will help youunderstand how the brain controls learning and behavior. Develop a newunderstanding of how the mind learns and retains new information. Examine thecore principles in detail and discover how to leverage neurological principlesto create sustainable behavior change both within the individual and yourentire organization. You will leave this workshop with a deep understanding ofcore principles of modern cognitive science, and you will be able to immediatelyutilize these ideas as you create eLearning that is tailored to the human mind.

You can register online for DevLearn and Art’s Pre-conference CertificateProgram. Do it today!