Toaccomplish more with fewer resources, many organizations are turning fromcostly traditional face-to-face (F2F) training to alternate methods, such asself-paced eLearning and distance learning. Distance learning is beneficial forvarious learning events, such as semester-long academic courses, which areoften asynchronous, and shorter events, such as Webinars, which are typicallysynchronous. Although asynchronous methods, where learners interact withcontent and each other on individual timetables, can provide significantadvantages, some learning experiences warrant synchronous real-time humaninteraction. Engaging synchronous distance learning can provide theeconomy of distributed learning while retaining the human element of F2Fenvironments. In this article, we summarize the techniques we used to convert afour-day F2F course to a synchronous distance format, highlighting designconsiderations, successes, and best practices.

A casestudy in transitioning to distance learning

To reducecosts through economies of scale and minimizing travel, a learning academywithin a federal agency is expanding its current programs by leveraging learningtechnologies. Through distance learning, the diverse talent and expertise foundthroughout the agency can be available to a broader audience.

To kick offits distance-learning effort, the agency chose to pilot a new course deemed idealfor distance learning because the topic is in high demand by 500 employees frommultiple locations. The distance learning option, using Adobe Connect™, wouldexpedite the training to these employees.

Considerationsand challenges

The instructionaldesign goal was to develop a blended learning course that we could teach effectivelyin both F2F and distance learning environments. Both an expert-instructor-ledapproach and synchronicity between the two formats were highly desired because thecourse content is highly dynamic, requiring frequent updates and practicalworking knowledge. The agency chose a model based primarily on synchronousdistance learning, because not only could it meet these requirements, but itwould also ease the cultural transition from the traditional F2F lecture formatto a blended format that increases learner engagement, promotes application,and improves workplace performance. Using the blended learning approach, courseactivities should employ a variety of methods including group projectsmimicking typical work assignments, self-paced eLearning, and interactiveclassroom presentations. The desired ratio of activity to lecture was 60/40. Wereferred to course instructors as facilitators to encourage departure from a“talking head” approach to an approach that encourages a learner-drivenenvironment that fosters collaboration among class members.

Achieving the goal

Effective learning involves participation. Avoid usingsynchronous eLearning tools to simply “broadcast” from the instructor orteacher (Wenmoth 2008).

We designed the key activities of the course for both F2F anddistance formats. After conducting two F2F pilots, the goals of the two distancepilots was to ensure that the learners in the distance classes had similarexperiences to what the learners in the F2F classes did, and that they achievedthe 17 course-learning objectives. Pilot challenges included preparingparticipants for the distance learning experience, executing the activities inthe distance environment, and engaging the learners in a distributed situation.

Preparing participants

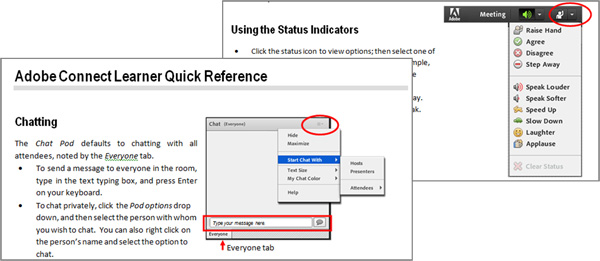

Participants in the distance pilots fell into threecategories: learners, facilitators, and observers. Learners were both experiencedand inexperienced in the course of study. Facilitators weresubject-matter-experts (SMEs) and technical staff, known as a producer or host.Observers of the pilot were course stakeholders and developers, whose purposewas to evaluate and refine the course based on the pilot results. Allparticipants received access to the environment and technical support beforeand during the class as needed, including live support. Participants had accessto Help resources that answered frequently asked questions and assisted withenvironment features, such as using status icons or chat. (Figure 1)

Figure 1: Help resources provided participant support forenvironment features.

Executing activities

Course activities included discussions, polls, knowledgechecks, and team presentations in the main room and team tasks in breakoutrooms. Prior to class, the hosts, facilitators, and technical staff reviewedand practiced the timing and execution of the activities in the environment.

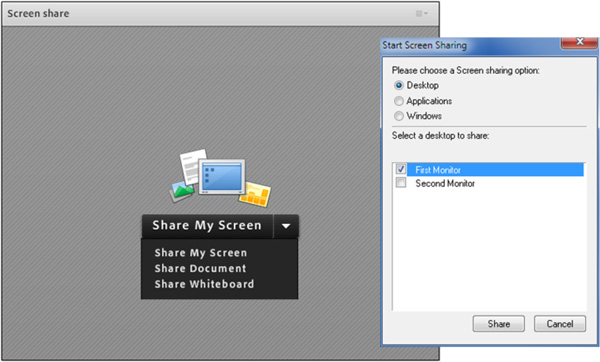

We modified some activities from how we executed them in theF2F pilots, enabling learners in the distance environment to focus on thecontent instead of the tools. For example, although the distance environmenthad drawing and text tools for team presentations, it was easier for thelearners to use familiar tools, such as Microsoft Word®and PowerPoint®, and share their screens rather than to use the toolswithin the online environment. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: It was easier for participants to share theirscreens than it was for them to use unfamiliar drawing and text tools in theonline environment.

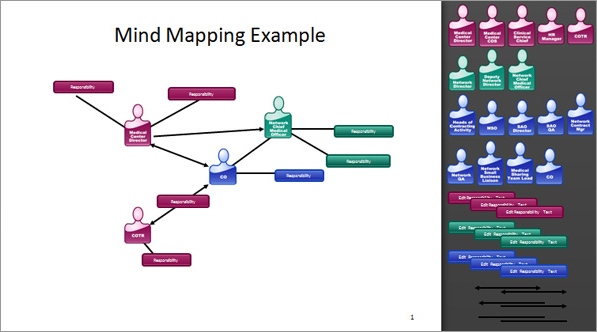

Another modified activity was to create a mind map connectingthe various roles and responsibilities in a process. In the F2F pilots, teamsused whiteboards to draw their mind maps, but in the distance environment,drawing and adding text boxes, even in PowerPoint, was time consuming anddistracted from the objective of the activity. We solved this problem bycreating a single-slide drag-and-drop activity with pre-made objects thatenabled the learners to focus on the content and achieve the objective. (Figure3)

Figure 3: A single-slide drag-and-drop activityfor the mind map, using pre-made objects, enabled the learners to focus on thecontent.

Engaging learners

Due to overarching requirements, the pilot classes consistedof four consecutive days of mostly synchronous training. During the F2F pilots,facilitators and learners seemed comfortable with lecture between activities. Inthat environment, facilitators interpreted learners’ body language to senselearner engagement. In the physical classroom, learners were able to focus withminimal job-related distractions, such as e-mail, and they appreciated theopportunity to network with others in the room.

In the distance environment, the design encouraged facilitatorsto use discussion as a tool for both learner participation and learnerengagement. Discussion areas promoted textual interaction in support of theaudio discussion. The distance environment influenced a beneficial shift incourse delivery from lecture to more discussion, which not only engaged thelearners, but helped with social interaction, a key benefit of F2F.

To help learners focus during the class, facilitatorsencouraged them to use chat and status icons and employ distance-learning bestpractices, such as using a headset, creating an out-of-office reply for e-mails,and posting a Do Not Disturb sign.

Host and facilitator preparation and practice in the distanceenvironment were critical in maintaining learner engagement. This preparationenabled the class to flow at an appropriate pace and allowed facilitators tofocus on content delivery and learner engagement.

Successes

The distance pilots were successful – a distributed group ofindividuals achieved learning objectives for critical course content. This wasdue to the employment of techniques fundamental to the successfulimplementation of synchronous distance learning, namely, creating a socialpresence, generating interaction, and providing technical support.

Creating social presence

Class discussions in DL [distributed learning] courses willrarely be able to provide the same visual and auditory clues to the instructorand the learners that they can receive in a classroom course. For that reason,it is important to develop social presence using other methods (Marcellas,Kurzweil, and Smith 2010).

As a pre-class assignment, we asked learners to add theirinformation to the class roster. The class roster provided contact and workinformation for networking, and an opportunity for learners to introduce theirpresence in the class and build a community. To further promote a socialpresence, best practices suggest a visual roster with each participant’s photoor a map where learners can mark their location.

Content teasers (short ice-breaker-type activities based oncourse content) throughout the length of the class supported team building, informalcontent reinforcement, and learner engagement and collaboration. Normally, acontent teaser in the morning served to draw in the learners. It also workedwell after lunch to help refocus energies. Through collaboration and a healthydose of competition, content teasers provided opportunities for socialinteraction and a little fun.

A chat window was always available, and it helped with formaland informal interaction. For example, the facilitator posed open-endedquestions to the class and multiple learners responded at the same time in thechat window. The facilitator could then incorporate the answers into thepresentation. Informally, when a learner had questions regarding a specifictopic, another learner could provide a link to an online resource. Chat helpedto maintain open communication among all participants.

Generating interaction

Virtual classrooms only work when instructors employfrequent, relevant (job-based) interactions (Kwinn 2007).

The facilitators asked learners to share their experiencewith a topic and used those comments (text and verbal) to reinforce content andrelevancy. Open-ended questions provided discussion points to customize thecontent to the learners’ needs. While a typical Webinar is mostly monologue,training should include dialog.

Team activities in breakout rooms served to achieve courseobjectives and provide opportunities for learners to interact in smallergroups. Each breakout room had its own conference line. Learners exchangedideas and shared accountability for the team task. Team members took turns asthe team captain, leading the task, and sharing his/her screen. Team activitiesin breakout rooms gave learners an opportunity to share their experience andcollaborate.

Knowledge checks employed diverse polling strategies, includingmultiple choice and multiple answer questions, chat/discussion (text andverbal), and use of status icons. This variety of interaction helped tomaintain learner engagement (Clay 2011).

A wiki served as a parkingboard, where learners could note questions for discussion at a more appropriatetime during the class. Best practices also suggest providing a wiki ordiscussion board prior to class where learners could note questions and/or anapplicable real-life situation usable as an example in class. Using currentwork challenges or examples from the learners enhances engagement, motivation,and relevancy.

Providing technical support

The Producer’s job is to be sure that the software, thecontent, the presenters, panelists, and speakers, as well as the participants,can get up and running and have a relevant, successful session (Hyder 2007).

For this project, numerous individuals, including agency trainingspecialists and instructional designers, filled the role of the producer.

Prior to the class, course facilitators attended preparationsessions that provided practice working with a producer to execute activitiesand engage learners. Practice in the online environment was vital to thesuccess of the project. Learning the facilitator’s resources, such as how topoll or view activities in breakout rooms, assisted with their preparation andexecution of the course in the online environment.

Prior to class, we asked learners to test their system andenter the online environment. Upon entering, learners accessed a brieforientation covering distance learning recommendations and features of theonline environment. We gave learners an opportunity to practice interacting inthe environment, and technical support was available before and during theclass.

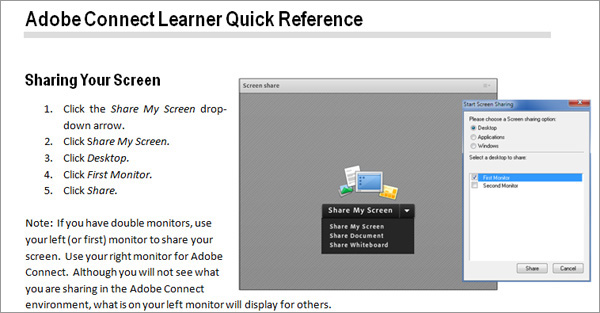

During the class, the producer/host assisted as needed andcoached all participants to perform tasks associated with course activities,such as sharing a screen for a team presentation. Quick references helped withthe use of technical features. (Figure 4)

Figure 4: Quick referenceshelped participants use technical features during class.

Best practices

Synchronous eLearning improves employee productivity byreducing travel strain, eliminating unnecessary time away from home, andconnecting with learners at their point of work (rather than in unfamiliarclassroom environments) (Murray 2007).

Organizationswishing to enhance their learning offerings through incorporation of distancelearning methods, and actively improve the distance learning experience, couldbenefit from the following best practices.

Weave with asynchronous

The asynchronous learning assets provide both the means andopportunity for creating a pre-existing knowledge base. This enablessynchronous event facilitators … to focus on higher-order learning objectives,within a limited timeframe, in ways in which they were not previously able todo. Adding asynchronous events after synchronous events also provides … a meansto more adequately assess learning… (Chrouser 2008).

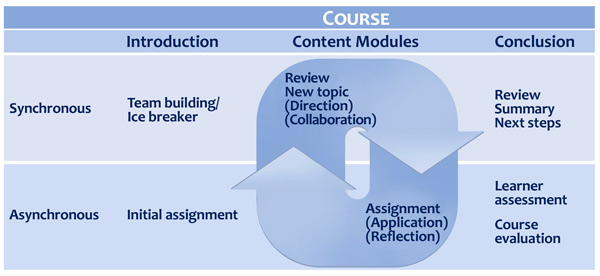

Best practices recommend dividing the class intonon-consecutive days with asynchronous activities between synchronous sessionsenabling learners to apply their learning and reflect on content. Figure 5shows how you can structure a course that blends synchronous and asynchronousactivities.

Figure 5: Blend synchronous and asynchronous activitieswithin a course.

Blending the modes of delivery requires learners to be moreaccountable and pull the content rather than having it pushed to them. Otherforms of asynchronous learning could include application activities such as:

- Collaborating with a small groupto create a mock work-product based on a case study

- Interviewing co-workers at theirlocation, and organizing feedback to share with classmates in a synchronoussession

- Researching answers to providedquestions using organizational resources

- Preparing a presentation on acourse concept to teach at the next synchronous session

- Performing a procedure taught in asynchronous session, and documenting the results and any clarifying questionsto discuss at the next synchronous session

Promote distance learning

Communication and promotion of the learning experience areamong the most effective pull strategies (Moshinskie 2001).

After defining their vision for distance learning,organizations should proactively help their customers, including stakeholders,subject matter experts (SMEs), facilitators, and learners, embrace that vision.Organizations can encourage customers to transition from lecture-basedclassroom training to distance learning that employs a blend of educationalmethods by:

- Continuing to offer effective distance learning options. As learners and supervisors see the results from practical training that provides opportunities for immediate practice and refinement in the workplace, the demand for distance learning should increase,

- Marketing the benefits of distance learning, including decreased costs associated with travel reductions and time away from the workplace, and

- Providing instructional design and technical support, such as the distance environment itself and producers to aid in the smooth execution of classes.

Emphasize preparation and practice

A myriad of tips and best practices stresses the importanceof technical support and practice. Learners lose their way easily whentechnical issues occur, or when a facilitator stumbles due to lack of adequatepreparation. Establish back-up plans for environment dysfunctions or a loss ofconnection. Record synchronous sessions for use of learners who encounterunplanned circumstances, such as loss of power or a personal emergency. Recordingscan also become learner resources, for review after the session.

Practice is critical for producer’s and presenter’s success. Successfulsynchronous distance programs employ a talk-radio type of delivery with a host,SME, and producer (host and producer are two different roles). The host focuseson energy, engagement, and collaboration. The SME focuses on content andprovides instruction. The producer facilitates the technical aspects of thelearning event. In distance learning, delivery is critical and requiressignificant practice.

Conclusion

We achieved the goal of the distance-learning pilots in thiscase study; learners in the distance classes had a similar experience to learnersin the F2F classes. We addressed challenges by preparing participants,designing activities for the environment, and using the environmental featuresto engage learners. Learners were able to establish a social presence,participate in team activities and other interactions, and access technicalsupport as needed. Organizations can providehigh-quality training programs in a distance environment by capitalizing on thetechnology and applying best practices.

References

Chrouser, Kelley, as quotedin 144 Tips on Synchronous eLearning Strategy andResearch (California: The eLearning Guild, 2008)

Clay, Cynthia, From Blah to Aha! Six Strategies to Engage Your Online Audience,(Webinar presented by NetSpeed Learning Solutions, July 2011)

Hyder, Karen et al., The eLearning Guild’s Handbook on Synchronous eLearning (California:The eLearning Guild, 2007)

Kwinn, Ann et al., The eLearning Guild’s Handbook on Synchronous eLearning (California:The eLearning Guild, 2007)

Lewis, Martyn, The Case for Live Virtual Training, (Webinar presented by 3gSelling, October 2011)

Lewis, Martyn, Moving to the Virtual Classroom, (Webinar presented by 3gSelling, October 2011)

Marcellas, Karen E.,Kurzweil, Dina M., and Smith, Dale C., “Transitioning Classroom Based Learningto a Distributed Learning (DL) Environment,” (paper presented at the Interservice/IndustryTraining, Simulation, and Education Conference (I/ITSEC), 2010)

Murray, Matthew et al., The eLearning Guild’s Handbook on Synchronous eLearning (California:The eLearning Guild, 2007)

Moshinskie, Jim, Ph.D., “Howto Keep E-Learners from E-Scaping,” Performance Improvement,Vol. 40 No. 6, July 2001

Piskurich, George, “PreparingInstructors for Synchronous ELearning Facilitation,” PerformanceImprovement, Vol. 43 No. 1, January 2004

Wenmoth, Derek, as quoted in144 Tips on Synchronous eLearning Strategy andResearch (California: The eLearning Guild, 2008)