It’s always tempting to get excited about anew technology and design a learning program around it. This ignores the basicprinciples of collaborative learning. Instead, we should take alearner-centered approach and find the technologies that actually support thelearner. Online video is no exception to this rule.

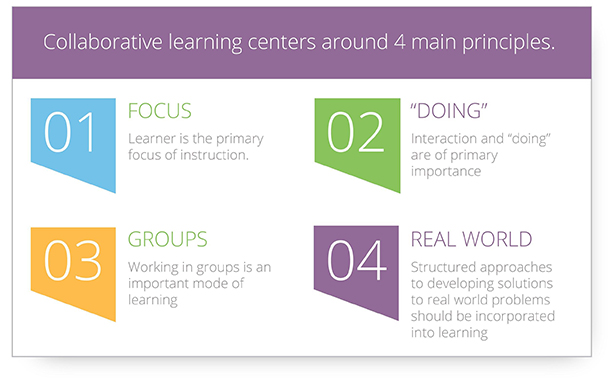

As you may be aware, collaborative learningcenters around four main principles (Figure 1):

- The learner is the primary focus ofinstruction

- Interaction and “doing” are of primaryimportance

- Working in groups is an important mode oflearning

- Structured approaches to developingsolutions for real-world problems should be incorporated into learning

Figure 1:The four principles of collaborative learning

When designing an eLearning solution, your motivationsoften involve cost savings, mass distribution of information, learning atscale, and convenience. The first pass at learning online often entailsuploading presentations that you would typically use in an in-person setting,adding some learner controls to advance from one content item to the next,adding some quiz questions, and maybe uploading a video recording of the in-personpresentation because online video makes the course more engaging. As we allknow, this method for eLearning falls flat.

Best practices

Fortunately, today’s technology offers somuch more. The interest in using online video for learning is well supported byRichard Mayer’s multimedia learning modality principle: Explaininggraphics with audio yields an 80 percent average learning improvement (seeReferences). However, even the highest-quality professionally produced video ispassive. Press play, sit back, and watch. Just adding video to an online coursedoesn’t make the course better. Follow these best practices to get the mostcollaborative-learning value from your online video use.

1. Record in the first person

At the recent FocusOn Learning 2016 Conference,Dr. Hans de Graaf pointed out that onlinevideo is a one-to-one medium (the link opens a recording of his presentation; scrubahead to about 42:12), giving you an opportunity to keep the learner central tothe experience. He advocated for “human” personalization of your recordingdevice. This concept is further supported by Mayer’s personalization principle, based on research by Byron Reeves and CliffordNass (see References). The research establishes that a personal, conversationalstyle is more effective for learning than formal language is. Research alsoindicates that using a character to provide instructional advice can improvelearning. Fear not! This user-agent character does not need to be a “talkinghead” to be effective—a human voice is sufficient.

2. Use an environment thatsupports video interactivity

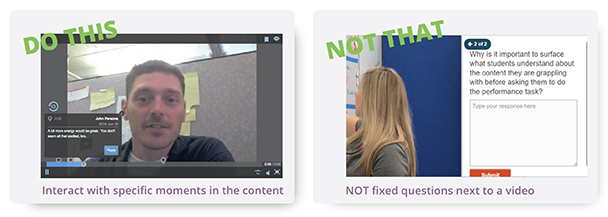

Standard online video isn’t typicallyoffered in an environment that supports or encourages general interactivity andthe other principles of collaborative learning. Developers often drop videointo otherwise effective eLearning systems without any connection betweenmoments in the content and the learners. As Mayer emphasizes with the spatial contiguity principle, make theconnection between the learner interaction and the content as close as possible(Figure 2).

Figure 2:Make the connection between the learner interaction and the content as close aspossible

Once this connection between the learnerand moments of video content is made, you can get your learners to interact andreact to the content in ways similar to an in-person interaction. For example:

- Start a discussion prior to the start of anexample in the video, asking learners to speculate on what will happen next

- Ask learners to choose from a list what theperson in the video should do next; jump the learner to a different part of thevideo depending on his or her response to see how each answer choice might playout

- Ask learners to find and mark a particularcontent item within a video—for instance, a speech course may request studentsto identify the main point or transition points, spot the error in a safetyvideo, identify the critical moment in a customer interaction, etc.

You get the idea. Connecting to moments inthe video allows you to create interactive engagements similar to those youwould normally have with an in-person setting.

3. Give the learner some control

Mayer’s segmentingprinciple advocates providing learners with some control over theirexperience. Segment your content into individual steps so that users can moveat their own pace. With online video content, segmenting techniques include:

- Making shorter videos to cover each stepand sequencing them in a playlist so that users can move at their own pace

- For longer videos, creating a table ofcontents or chapters to allow users to jump in right where they need to

- Adding questions between topics todetermine whether learners can skip over content they already know

4. Combat forgetting

With your active learning techniquesembedded in the video content and learner controls in place, you still need toaccount for getting your learners to retain their new knowledge. The Ebbinghaus forgetting curve indicates that as much as 70 percent of informationmay be lost after 24 hours. To combat this tendency, you must help yourlearners encode, store, and retrieve the information. For example:

- Provide online learners with the same toolsthey use offline to create bookmarks, make notes, and tag the video content

- Schedule video availability to prepare thelearner for a lesson, provide the core instruction, and then review materialsover multiple days rather than allow for continuous completion of the content

- Require learners to answer questions correctlyin order to complete watching content

- Provide printable downloads to post asreminders or use as an offline worksheet

5. Measure results

Collaborative online video learning maysound good in theory, but these days you are being asked to prove efficacy toyour management teams. Start by designing your online video training programswith specific learning outcomes in mind. Learners canpractice and demonstrate new skills through webcam or smartphone videorecordings. Using video-based assignments, you can rate those learnerrecordings from a common rubric and provide contextual feedback for any momentin a video response. Be sure to use a system that allows you to report out theresults of both video assignments and questions asked within the video content.

6. Allow teams to learn together

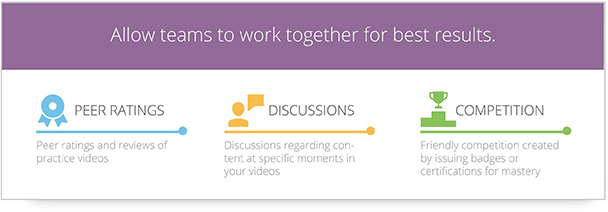

Working in groups is an important mode oflearning, but it’s difficult to do with many video solutions because thecontent isn’t aware of the learners (see Figure 3). Make sure your videosolution supports learner awareness so that you can offer:

- Peer ratings and reviews of practice videos

- Discussions regarding content at specificmoments in your videos

- Friendly competition created by issuingbadges or certifications for mastery

Figure 3:Your video solution should support learner awareness through these methods

Designa solution to meet your needs

Your real-world problems may be addressedin many different ways. Here are some ideas using collaborative video to getyou started. Do you need to:

- Answer questions and provide a forum for practiceand discussion of best practices following an in-person training?

Create a community of practice with review and/or reference videos. Elevate learners to leaders as they demonstratemastery of skills. Obtain certification through video-based demonstrations ofknowledge and skills.

- Minimize subject matter experts’ traveland time spent training so they can focus on what they do best instead?

Record SME presentations, assign to usergroups, enable Q&A with SMEs through in-video discussion, and add interaction to the videos as described above.

- Expose employees to rarely encounteredsituations to ensure they have seen these incidents before they encounter them andknow how to react?

Assign videos in peer groups or cohorts. Seed with in-video discussion questions. Assign response examples to ask people to practice their response to the situation. Require peer reviews and discussion.

- Capture organizational knowledge from a retiringpopulation?

Require video submissions of demonstrationsand presentations using tagging to facilitate curation. Complete expert reviewsof the content to pick the best examples in one group; then, publish thecontent to a library for the organization to explore. You can also combine thiswith a cohort-assignment approach for peer group learning.

- Level the knowledge base of participants in an on-sitetraining event so that people are getting the most benefit out of their face-to-facetime?

Provide videos of prerequisite contentseeded with questions to gauge knowledge, and direct people to the content theydon’t already know. Require them to complete this content before attending sothat the in-person portion of training can assume a level playing field. Youcan also require participants to add an introductory video about themselves andwhat they expect to get out of the training.

- Require practice and reinforcementafter training to improve retention?

Following a training event, assign reviewvideos with questions at key points to encourage the brain’s storage and retrievalmechanisms. If appropriate, require practice of skills that the employee’smanager or a peer group reviews. Make the reference content and review contentavailable in a library for “just-in-time” retrieval.

Excitement over online video certainly should not drive your learningprograms, but I hope these examples and best practices give you some ideas fortaking a learner-centered approach to collaborative video.

References

Clark, Ruth. “Six Principles ofEffective e-Learning: What Works and Why.” LearningSolutions Magazine. 10 September 2002.

https://www.learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/384/six-principles-of-effective-e-learning-what-works-and-why/?utm_campaign=lsmag&utm_medium=link&utm_source=lsmag

de Graaf, Hans.“Making Video Brain-friendly.” FocusOnLearning 2016 Conference & Expo. 10 June 2016.

https://www.elearningguild.com/conference-archive/index.cfm?id=7438&from=content&mode=filter&source=sessions&showpage=2&type=FocusOn+2016+Conference+%26+Expo&utm_campaign=fovideo1607&utm_medium=link&utm_source=lsmag

Mayer, Richard E. “CognitiveTheory of Multimedia Learning.” In TheCambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning, edited by Richard E. Mayer. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge UniversityPress, 2005.

Millis, Barbara J.“Student Learning Outcomes.” Cornell University Center for Teaching Excellence,2009.

https://www.cte.cornell.edu/documents/presentations/Student%20Learning%20Outcomes.pdf