Blended learning is the thing — training’s big talking point for the mid-noughties. Like sensitivity training, action learning, interactive video, accelerated learning, coaching and mentoring, and e-Learning before it, it has become a bit of a bandwagon.

Yet blended learning is more than just a fad. It’s a recognition that other approaches to training are simply not strong enough to work for all audiences, all of the time. Sometimes only a combination of learning media will do the job.

I’d like to suggest that blended learning is evolving into a new role, as our understanding of learning itself — and the applications of technology to learning — is also evolving. For in addition to previous uses of computers for learning, we now have informal learning. E-Learning producers (designers, developers, managers) may regard informal learning as a threat, but that would be a mistake, as I hope to show. One of the keys to understanding how informal learning changes our work is the realization that blended learning, whatever practitioners may have thought of it in the past, is actually a bridge between formal learning and informal learning.

Bridging that gap is not easy, and requires several steps and adjustments. It is up to e-Learning producers to take these steps. In this article, I will give you my thoughts on four challenges that confront us, and ways to meet them:

- Dealing with the various existing objections to blended learning;

- Incorporating non-formal learning into blended learning, as a transitional step;

- Coming to terms with informal learning; and

- Handling resistance issues.

Objections to blended learning

Because blended learning has become such a commonly used term, some who think of themselves as training cognoscenti regard it with scorn and cynicism. They may speak of it as another panacea to delude the masses, and one that is bound to fade into the background when we eventually realize it doesn’t work. This sounds harsh, and perhaps you doubt that anyone would hold such an opinion. Yet, I once went to a seminar during which the chairperson referred to blended learning as “the ‘B’ word,” something not to be mentioned in polite company.

Since blending is a concept that can arouse such strong passions in some of our colleagues, I’d like to take some time to consider the particular objections that you may hear.

“It’s nothing new”

One of the most common objections to the razzmatazz about blended learning is that it’s nothing new — blending is something we have always done. There is obviously some truth in this, because we can probably all think of some examples of training interventions that have successfully combined a variety of media. But to maintain that this has been in any way the norm is clearly wide of the mark. Most learning, of course, is informal — we don’t even know that it is happening. When it is structured and formalized, it’s most likely to be wholly on-the-job, if not wholly in the classroom, if not wholly online. Blending has been (and still is) very much the exception, not the rule. That’s not surprising because blending is a hassle — it takes more planning and more co-ordination.

“It’s just marketing”

Cynics may also claim that blended learning is just a rebranding exercise, carried out by e-Learning vendors who have hit upon hard times after the bursting of the dot-com bubble. Again, there is something to say for this view. Most companies that claim to be in the blended learning business used to be — you guessed it — e-Learning companies, not classroom trainers. They even tried to make the term blended learning their own, referring to it as a mix of “e-Learning and traditional methods.” This definition still dominates, even though it is unhelpfully restrictive, not to say condescending about the so-called “traditional” methods.

“It keeps the classroom instructors happy”

The e-Learning community may retaliate by claiming that blended learning is in fact a sop to the classroom community, allowing them a piece of the action in a world of learning that is already dominated by the computer. (See Sidebar 1.) This view is hard to justify. Computers are playing an increasing role in learning, but have major limitations as anyone can see. Even the most optimistic forecasts for e-Learning don’t see it replacing the classroom as a mechanism for delivering formal training.

According to my calculations, e-Learning is now bigger than the classroom. Much bigger. Now that got your attention. Let me explain how.

The American Society for Training and Development’s State of the Industry Report 2004 showed e-Learning as 29% of all formal training (up from 8% five years earlier) and the classroom at 63% (down from 80%). Then, it has long been known, and proven by a number of major studies, that most of what people learn at work is not as a consequence of any formally planned interventions. A typical estimate is just 20%. The rest occurs quite naturally as we do our best to cope with the demands of our jobs by hunting down information, asking opinions, comparing alternative solutions, trying things out, and learning from what happens. I’m sure you’ll agree that a fair proportion of this comes through communication with peers and with experts, both within and beyond our immediate working environment.

|

|

Formal |

Informal |

Total |

|

E-Learning |

4% |

24% |

28% |

|

Classroom |

14% |

0% |

14% |

|

Other |

2% |

56% |

58% |

|

|

20% |

80% |

100% |

Now, here’s where we need to make a judgement call, because I’m not aware of any up-todate research. What proportion of this communication would you think is online, through email, instant messaging, Web conferencing, and forums; or through browsing the intranet and searching with Google? How much higher could this rise when blogging extends its reach into the world of work? I’d say a conservative 30%, perhaps even 50%. The remainder is likely to be a mix of face-to-face communication, print and telephone, perhaps even TV and radio. None of this is going to be in a classroom.

Time to total the figures: Let’s say, conservatively, that e-Learning represents 20% of all formal learning (or 4% of the total) and 30% of informal learning (another 24% of the total). That’s 28% overall. If classroom training is 70% of formal training (being generous), then its total contribution is 14%. I know it’s a long time since I passed my Math exams, but I believethe e-Learning contribution is double that of the classroom. (See Table 1.)

So, what does this jiggery pokery tell us? Perhaps it just confirms that there are “Lies, damned lies, and statistics.” More importantly, I believe, it emphasises the contribution that networked computers are making to all aspects of our lives, and that includes how we learn. Even without the interventions made by trainers and e-Learning suppliers, we have become empowered by the phenomenal improvements that have occurred in our access to information and expertise. We are becoming ever-more-independent learners, less and less reliant on the formal inventions of learning professionals. That’s what all good teachers and trainers have always wanted, so I believe there’s cause for a modest celebration.

“It’s about control”

Blended learning has also been harshly criticized, if not completely written off, by advocates of new, less formal approaches to learning (you know, those that take advantage of new technologies such as blogs, wikis, and Podcasts) as just another attempt to impose highly-structured and formalized instruction on employees who would prefer to be in much greater control of what they learn, and when and how. They see blended learning as being yet another repackaging of the same tired old ingredients, typically classroom instruction and what used to be called CBT (computer-based training, i.e. interactive, self-study lessons).

Worse than that, perhaps, is the accusation that, where e-Learning is used in the blend, it is restricted to covering the boring knowledge material which trainers hate training and learners hate learning. In his book Lessons in Learning, e-Learning, and Training, Roger Schank laments that, “The part that is assigned to e-Learning is the rote learning part — the facts followed by the answers. That stuff doesn’t stick, and for the most part trainees hate it. When you hear the word ‘blended,’ run.”

This viewpoint of blended learning, while appealingly cynical and superficially fashionable, is off the mark in at least two respects. First, I believe that there remains a place for formalized instruction — and a very valuable one at that. Structure in learning is important when you don’t know what you don’t know, nor (once you realise what you don’t know) do you know how to go about rectifying the situation. You are a dependent learner — dependent on an expert, who has done all this before, to guide you from ignorance to mastery. The more dependent you are, the more you appreciate the structure that goes with formalized instruction, whether that’s in the classroom or online.

Structure is also helpful if you’re an employer and you need to be absolutely sure what knowledge and skills your employees have been exposed to and what they have learned as a result. As valuable as informal learning may be (and at least 75% of all learning is informal by all accounts), it doesn’t show up as a pass or fail on your learning management system. That matters when you’re responsible for training pilots, ensuring compliance to key legislation, or a thousand other critical training challenges.

Bridging the gap

The criticism of blended learning by informal learning enthusiasts falls down in one other important respect — it assumes that blended learning cannot make use of new, relatively informal, methods and media. Now strictly speaking, no learning activity that is set up with an explicit learning objective can be accurately called “informal.” However loosely it may be structured, however discretionary, however unsupervised — if the learning activity is deliberately included in a program to facilitate learning, then educators would like us to call it “non-formal.” That’s fine, this distinction can be conceded — blended learning can be as non-formal as you like. Here’s for non-formality!

It’s true that most blended learning is a combination of formal, you might say traditional, elements — a bit of classroom, a bit of CBT, perhaps some on-job instruction. But there is no reason whatsoever why this should always be the case. By including non-formal elements, blended learning not only becomes more relevant, more embedded in real-work behaviour and therefore more powerful, it also acts as an important bridge from formal to informal learning. (See Figure 1.) It demonstrates the potential for learning in everyday work activity. It encourages independent learning.

Figure 1 By making use of non-formal methods and media, blended learning fills the gap between formal instruction and informal learning

Coming to terms with informal learning

E-Learning has been consolidating — which is what you do when you’re worn out from too much change and need a breather. We’ve been honing our skills, listening to feedback, refining our strategies and making pacts with our enemies, if you will (a development also known as blended learning). I am writing this article in the midst of the World Cup, so I hope you will forgive me for using soccer as a metaphor. It seems to me that the e-Learning industry, used to being on the defensive and doubled up trying to recover its breath, has completely taken its eye off the ball; it has failed to anticipate an attack from an unexpected direction and ended up deflecting the ball off its backside and into the net for a spectacular own goal.

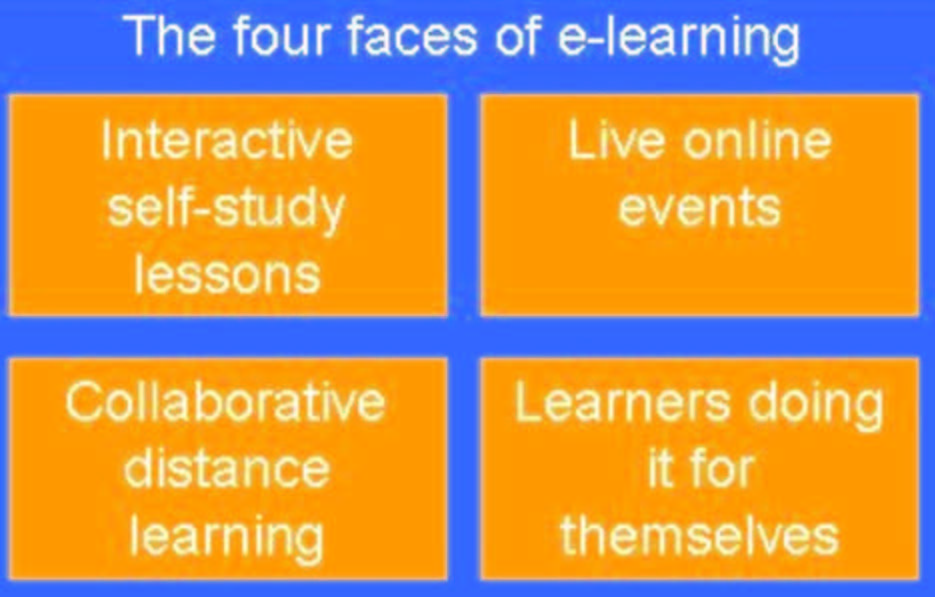

Until recently, I was complacent in the view that there were three primary applications for computers in learning. The first, and the most dominant, is the use of computers to deliver interactive, selfstudy lessons (you know, CBT in a Web browser). The second is the use of the Internet as a channel for the delivery of longer distance learning courses incorporating a wide range of activities, supported by tutors and encouraging collaboration between learners. And the third is the delivery of short, live online events using virtual classroom software.

Well, it never pays to become too smug about a model because the real world pays models no respect. My complacency was rudely interrupted by what appears already to be the most exciting new development of them all. This fourth big idea for e-Learning has evolved as a natural function of improved tools for online collaboration and the increasing self-confidence of Internet users. It can be effectively summarized as Learners doing it for themselves. (See Figure 2.)

Figure 2 The four primary applications of computers to learning

I say “learners,” but it’s hard to identify them as such — they don’t wear school uniforms or sit behind a desk. Learners in this context are just people looking to get things done and using their initiative to overcome any obstacles in the way (like being short of information or not knowing how to go about doing something). They can do this because they are now empowered by software tools that are incredibly easy to use yet awe-inspiring in their potential.

Search engines and forums

First port of call is of course Google — not a new phenomenon, but one that plays an increasingly important role in everyday life. If you still have more questions than answers, then simply Ask Yahoo! or submit a query to one of the thousands of forums addressing every topic imaginable. You will buy books, watch TV documentaries, consult with experts, even go on training courses, but only if you can’t find what you need online.

Weblogs

But Google’s not enough and Yahoo! is not enough, because with Google and Yahoo! you’re still essentially a passive recipient. You are not in a position to challenge or debate. More importantly, you don’t have the opportunity to publish your own thoughts and opinions, to become a provider as well as a recipient.

With the new tools, everyone’s a publisher, everyone’s a teacher. It’s midway through 2006 and there are something like 30 million Weblogs (online journals, more familiarly called “blogs”), with more than 30 thousand being discovered daily. Blogs allow people like you and me to publish our thoughts and experiences to whoever will take notice. They allow us to make contact with others who are facing similar challenges and who may be able to help us. They provide us with the broadest possible range of views and perspectives, often in stark contrast to the “official view” or the hysterical outpourings of the mass media.

Wikis

If you can’t find the reference information that you’re looking for online, why not publish your own? “Wikis” are websites created by their own users, in collaboration with each other. You want to add or edit an article, just go ahead and type it in. You want to challenge the accuracy or authenticity of a contribution, go right ahead and say so.

Wikis are succeeding where complex knowledge management systems have failed so spectacularly. Perhaps this is because volunteers drive them; perhaps because they’re so easy to use; perhaps because, like so much of Internet culture, they have emerged as a solution that people have worked out for themselves, rather than being imposed on them by remote software “architects” and the experts from head office.

For the finest example of how wikis allow learners to do it for themselves, visit the Wikipedia (http://www.wikipedia.org), where tens of thousands of “amateur” contributors are creating their own online encyclopaedia. The English language version of the Wikipedia already contains more than a million articles, with a completeness and accuracy that matches the Encyclopaedia Britannica (as evidenced by a recent study by Nature magazine (see http://www.nature.com/news/ 2005/051212/full/438900a.html).

Podcasts

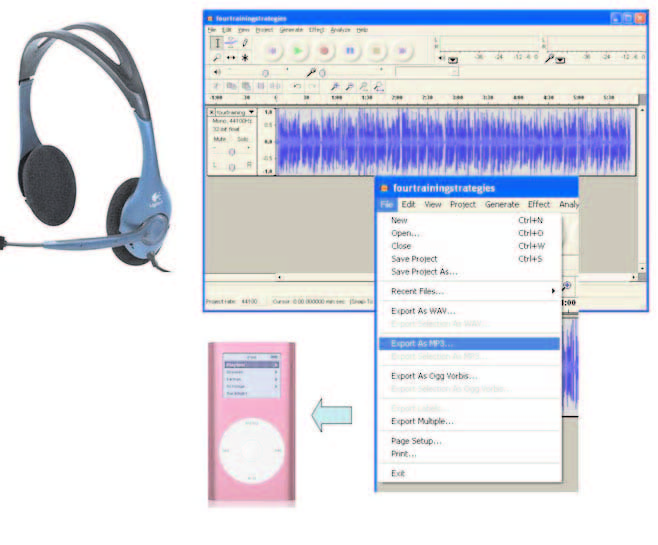

Podcasts are another interesting option. In case you’ve been away for rather a long time, let me explain what Podcasting is. (See Figure 3.) First, you need an iPod or some other form of MP3 player, and a computer with an Internet connection (actually a PC on its own is enough as long as it will play back audio, although this is nowhere near as cool). Then you subscribe to the Podcasts that you’re interested in. These are typically audio (although video Podcasting, or Vodcasting, is also a possibility) and composed primarily of speech rather than music. You could listen to your favourite radio programs as Podcasts, or the daily ramblings of an audio blogger recorded on her laptop, or fascinating little learning nuggets prepared by your training department.

Figure 3 The key elements required for podcasting are simple.

You’ll need some special “Podcatching” software, such as Apple’s own iTunes, to regularly check to see if new editions of the Podcasts to which you have subscribed are available. Download them to your PC and then transfer them to your portable player and all you have to do is listen, on the train, walking to work, in the gym, at your desk, or wherever you like.

Now Podcasts have a certain glamour, but let’s not forget that they are just sound recordings. When it comes to learning, sound recordings have never before had much of a role to play, and they are not going to change the world this time round. There are obvious limitations, not least the fact that listening to a Podcast is a passive experience — you can’t ask it questions and it can’t ask you any either. And recorded audio is not self-paced — it goes at the speed of the speaker, which may be much too slow or too fast for your taste. If you want to hunt down information, you’d be better off with a transcript. But listening to a podcast is not about hunting down anything; it’s what marketing people call a “lean back” experience. It’s reflective and low-stress. It’s enjoyable. Most of us do plenty of “leaning forward” in front of our PCs during the working day. Listening to a Podcast provides a welcome break from incessant messaging. Who knows, we might even learn something.

Learners on their own

This fourth big idea for e-Learning represents the ultimate learner-centered approach: learners identify their own needs, work out how best to meet them, implement their own training plan, and then evaluate their own results. What they don’t do is wait for teachers and trainers to do this for them. This approach is not completely learner-centered because teachers still play an important role— it’s just that those teachers are more often than not other learners, trading their expertise for yours.

What we’re seeing here is, of course, simply another manifestation of informal learning, the way that most learning has always been achieved. What’s different is the scale of the operation: the pool of over a billion potential teachers and learners, the literally uncountable Web pages, blog postings, and Podcasts. If, as professional teachers and trainers, we feel under threat then we are missing the point. We cannot hope to be everyone’s teacher — there simply isn’t the time. If we embrace the fourth big idea, we take a significant step in helping our organizations to establish a truly sustainable learning culture. And hasn’t that always been a strategic goal of the learning and development department?

Taking the plunge

So how can blended learning incorporate methods and media normally associated with informal learning? Well, perhaps the most obvious way is the use of Weblogs by learners to maintain an ongoing learning journal, starting before the course (or whatever it is you call the formal bit) and extending on well after, if not indefinitely. Blogs encourage reflection, allow learners to communicate their successes and their frustrations, and provide an opportunity for tutors and fellow learners to offer encouragement and assistance. They help to build communities of learners that persist long after a formal event is consigned to history.

Wikis provide a similar advantage. They allow learners to work together to build a body of knowledge from which they and all future learners can benefit. They remove the burden on trainers and subject experts to be the providers of all useful content. They encourage the notion that everybody’s a teacher as well as a learner.

So, what have Podcasts got to do with informal learning? Well, not much, if they contain instructional material created by trainers and subject experts. But imagine this scenario: you set your students off on a “Webquest” to hunt down information that’s relevant to the course. Their task is to summarise their findings by creating their own Podcast, which they then share with their fellow students. I have been using this technique for the past six months on a series of online courses. I anticipated all sorts of technical support problems and a requirement for a great deal of coaxing and cajoling on my part. My misgivings were completely misplaced, because the activity proved to be immensely popular, went without any sort of technical hitch, and made a great contribution to the learning of all concerned (including me).

Of course, the non-formal elements in a blended solution aren’t constrained to online technologies with strange names. There’s nothing to prevent you providing opportunities for face-to-face collaboration, teleconferencing, maybe even reading. There are no rules for blended learning, other than the requirement to be effective and efficient. Using your imagination to incorporate a wide range of non-formal methods and media is optional but highly desirable.

Handling resistance

Unfortunately, integrating non-formal learning elements into your blended solutions is not going to be as easy as turning on a tap. First of all, this is not going to be what learners are expecting, and they may need more than a little encouragement to believe that what they are being asked to do is not just formal learning in disguise, perhaps a trendy new training game — or worse still, a new form of assessment. Secondly, there may well be a misalignment between the learner’s goals for completing the program and your own aspirations.

There are probably three main reasons why a learner is taking part in a training event: (1) it is compulsory, such as most compliance training, (2) it leads to a valued qualification that will positively enhance their career prospects, and (3) they have chosen to do it because they see it as an opportunity to develop their knowledge and skills. Let’s take these in turn and see how they may impact on your chances of making a success of non-formal learning.

With a compulsory program, you may experience some resistance from participants to sharing their experiences and participating fully in collaborative activities. This may be because there is some resentment to having to do the training (perhaps they feel they don’t really need it). It may be because they fail to see what’s in it for them; it may also be that the experience is not of sufficient duration for participants to feel that the investment in establishing relationships with other learners is really worthwhile.

You have a number of choices if you want to persist with your strategy and make a success of the non-formal elements: you could make the activities themselves compulsory, which would ensure participation but may cause further resentment; alternatively, you could attempt to overcome the handicap that the training is compulsory by engaging learners fully. Do this by building on their past experiences, ensuring the content is relevant to their priorities and problems, and providing them with greater control over the learning process — in other words, treat them as adults.

You may experience a different kind of resistance to non-formal methods if you are responsible for a certificated course that leads to a valued qualification. Entry to the course may be voluntary, but more cynical (some may say pragmatic) participants may well have the goal to get into the program, get the qualification, and get out as soon as possible. They are not interested in the learning content, just the piece of paper. Even if the participants on this course are young, technology-literate, and, outside work, engage in online communities such as MySpace, they may be still be reluctant to go the extra mile and build collaborative relationships with their fellow students, particularly in a distance learning context.

Clearly, a great deal depends on the quality of the facilitation you provide. Again, you could make some participation mandatory, knowing that learners will be forced to comply if the qualification depends on it; but this compliance could be minimal and cursory, merely “going through the motions,” when what you are trying to establish is a genuine sense of community. As before, your best chance is to engage your learners with the subject so completely that they will really want to take advantage of all opportunities to develop their interests further.

The third category is much less of a problem. Here learners are participating in the course because they want to — they are genuinely interested in the subject and will take advantage of any opportunities that you are able to provide for learning from each other. In this situation, the non-formal learning elements mirror the informal most completely — there is a clear and relevant need for information and the learner is fully motivated to exploit all avenues to pursue it.

What happens after we cross the bridge?

If blended learning is a bridge, then we should devote some attention to what lies on the other side and whether the crossing is going to be beneficial, both for the learning and development community, and for those they seek to serve, the learners and the organizations for which they work. Well, in my opinion, the crossing is indeed worthwhile for all parties. Across the bridge lies a land where learning is truly informal and completely natural; what Jay Cross likes to call a learnscape (See Natural Learning by Jay Cross at http://metatime.blogspot.com/2005/10/natural-learning.html):

“Putting natural learning to work is more like landscape design and gardening than traditional instructional system design. All of life is interconnected. Organisms cannot live independent of their ecosystems. Self-service learners are connected to one another, to ongoing flows of information and work, to their teams and organizations, to their customers and markets, not to mention their families, friends, and friendship groups. We can improve their connections and nurture their growth but we cannot control them or force them to live.”

In a learnscape, perhaps the one word that would be used rather rarely is learning. The process of learning — so integrated in day-to-day work that it would be almost indistinguishable from other activities — would be completely taken for granted.

In this environment, all available communication media, including face-to-face interaction, print, the telephone, and text messaging, will facilitate learning. However, the primary catalyst for communication and collaboration will be online media, using the Internet and organizations’ own intranets. The online media that are most commonly employed in organizations now — email, instant messaging, and simple, one-way Web publishing — will continue to make an important contribution, but the key role will be played by social networking tools not unlike those found in sites such as MySpace.

These tools will replace the unwieldy and unworkable knowledge management systems that have failed so spectacularly to bring about the easy knowledge capture and exchange for which they have been expensively designed; they will also marginalize those learning management systems which have been designed only to plan, organize, and control the process of formal learning.

So what will these tools look like? Well, users will need to spend some time introducing themselves and explaining what they can contribute (in terms of their experience and expertise) and what they are seeking (in terms of their current and future work and career priorities). These user profiles will be vital because they will allow users to connect with others with similar interests and to form communities to serve their joint interests. We will not need to establish these communities from the top down; they will form naturally and spontaneously because members feel they will be valuable. They will close just as easily when their purpose has been served.

There will be some familiar mechanisms within these tools. Users will be able to upload and share documents and other files that are of common interest. They will maintain blogs in order to share their experiences and their opinions. They will use wikis as a way of capturing knowledge, which the community as a whole can utilize for reference into the future. They will often extend to include project management facilities such as task lists and schedules, so they become, in effect, shared workspaces. An interesting example of this sort of tool is Elgg (http://elgg.org), described on its Web site as a “learning landscape,” although there are probably others which will do the job well, many of which are likely to be open source.

Many, mainly younger, users will find it completely natural to use these tools because they so closely resemble the Web tools they use socially. They will take easily to knowledge sharing, because they have already learned that this is invariably of benefit to all parties. But older learners will discover the benefits as well. I’ve included a short story with this article (“Barbara’s Tennis Holiday”) to illustrate how this might happen in a place not so far from you, at a time not so far in the future.

Those without these insights may continue to hold to the old dictum of knowledge equals power; unless they have, of course, crossed the bridge, and learned how to learn through the non-formal collaborative activities they have experienced by participating in innovative blended learning solutions.

References

Lessons in Learning, e-Learning and Training. Roger Schank, published by Pfeiffer Wiley (2005).