Interesting, relevant multimedia elements are essential to creating engaging eLearning. Obtaining these can be a challenge for eLearning designers and developers with limited resources to create photos, graphics, audio, and video.

An often untapped resource, open-access media, offers a solution for the budget-strapped eLearning designer.

The best-known open-access licenses for photographic images are the range of Creative Commons licenses. According to Barbara Waxer, an author, trainer, and educator who teaches at Santa Fe Community College, it’s possible to find Creative Commons–licensed photos on a multitude of sites. These include:

- Free for Commercial Use

- WOCinTech Chat, which shows primarily women of color in technology roles

- MMT

- Flickr (search by Creative Commons license)

- FreeImages, which also offers vector graphics

Photographs and graphics are not the only media that instructional designers and other eLearning professionals can find with open-access licensing. Waxer lists sites offering music and other audio files, videos, and more; here’s a small sampling:

- Freesound offers Creative Commons–licensed audio

- DryIcons offers icons and vector graphics

- VidsPlay offers free video footage

In addition, federal government agencies, public libraries, and other organizations and institutions often make resources available on their websites. Waxer lists literally hundreds of resources, along with tips and advice, on her website (link above).

Credit where credit is due

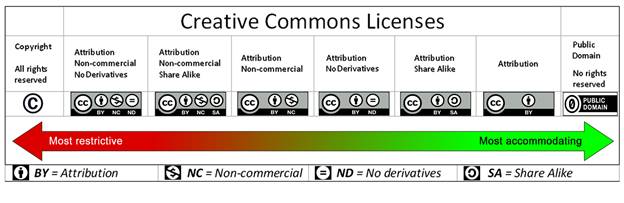

Figure 1: Creative Commons licenses vary. The best options for commercial eLearning are CCA (or CC By) and CC0. (Chart by Barbara Waxer)

“Creative Commons is not a magic unicorn,” Waxer said, cautioning that many designers and developers misunderstand key characteristics of open-access media. The biggest area where people run into trouble with Creative Commons–licensed material is that they think “it’s a magic pass to do whatever they want, and they don’t have to pay attention to the exact kind of license,” she said.

Figure 1 shows several Creative Commons license types. Copyright owners choose a license based on how much control they are willing to cede; they do still own the copyright, though. Waxer emphasizes that content creators must pay attention to the license type of the work they are using, since content with some license types, such as the “no derivatives” and “non-commercial,” is unlikely to be usable in commercial eLearning.

Most Creative Commons–licensed content and other open-access media require that the owner or creator be given credit. That attribution, or credit, has to be visible; putting it in metadata is insufficient. “You need to credit them in a place that someone can actually see it,” Waxer said.

Many of the resources Waxer lists on her website feature content from dozens or hundreds of creators; some are even from well-known photographers. Artists are sharing incredible work, often with CCA licenses—“What they’re saying is, ‘Use it, just give me credit,’” Waxer said.

It’s important to credit the actual copyright owner, not the site that distributed the image or another site where the content was republished. “It’s not just a rule,” Waxer said; it’s about respecting the artists whose work you are using.

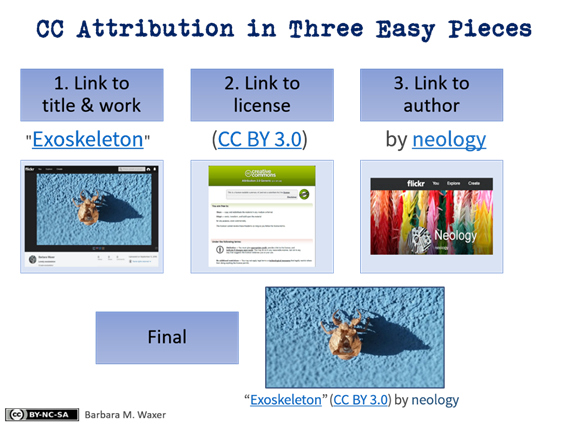

Creative Commons and other sites provide instructions for how to correctly credit or attribute a work. Waxer’s graphic explains a three-step process for accurate attribution (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Creative Commons attribution process by Barbara Waxer

It’s not only about copyright

A second area of confusion is the need for signed releases. Even though “the photo is in the public domain or the photo is saying I can do whatever I want with it as long as I give credit, the caveat—the exception—is if there’s a recognizable face, and you are using that face commercially. It’s not copyright law, but model release comes into play,” Waxer said.

While the person who takes a photo owns the copyright—and a Creative Commons license can resolve issues of use with the copyright holder—that does not translate into permission to use the image of a person or people in the photo. “Think of the photo as a container,” Waxer said. “You have a right to use that container, but you also have to be mindful of what’s in that container.”

A release is required even if the person’s face is not visible if the person can be recognized, Waxer said, citing the example of a photo of a large, unusual tattoo on a woman’s back. Even though the woman’s face was not in the photo, she successfully argued that she could be recognized. The solution is to avoid photos with recognizable people unless the licensing information mentions model releases.

Fair use and commercial projects

Finally, the question of fair use comes up often in Waxer’s workshops. Many eLearning creators believe that the fair use doctrine doesn’t apply to commercial use, but, Waxer said, that is not always true. “Transformative use is certainly acceptable for commercial use,” Waxer said, and de minimis use, “where I’m using so little that I’m not taking the market away from the original.”

A problem with the concept of de minimis use—the idea that the use of copyrighted material is so small or trivial that a court will not recognize it as an infringement—is that no clear definition stipulates how much of a work can be used safely. Many people believe that specific amounts, like seven words or four seconds, are permitted, but these amounts are not enshrined in the law. People are afraid of overstepping, Waxer said, and “that’s where they self-censor in ways that aren’t necessary.”

Determining fair use can be complicated, but knowing the basics can help.

- The so-called “fair use doctrine” is based on Section 107 of the US Copyright Act of 1976, which states, “The fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.”

- Section 107 also lists four factors that courts are to consider when determining whether a use is covered by “fair use.” These are:

- The purpose and character of the use; while commercial use is not explicitly excluded, courts might look more closely at commercial uses than educational uses, for example.

- The nature of the copyrighted work; courts have applied stronger protections to purely creative works than to nonfiction works.

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used is relevant. If you use an entire work, such as a photo, the court might be more strict than if you use a single sentence from a book or a single line of song lyrics; however, no firm guidelines exist as to what percentage of a work or number of words might cross the line.

- The effect of the use on the potential market for the copyrighted work or its value; courts consider whether the new product might harm sales of the original copyrighted product.

Finding the balance between too-restrictive self-censorship and crossing the line into a copyright violation can be tricky.