In the Guild’s most recent research report, Making mLearning Usable: How We Use Mobile Devices,field investigators (Guild members and others interested in mobile learning) gathered observations on how people touch and interact with tablets such as the iPad, iPad mini, Galaxy Note, and Nexus 7. They sent in 651 observations on a mobile-friendly web form from 22 countries about how people use their tablets. We simply didn’t have this data before (even though we are developing learning for these devices)!

This is called crowdsourcing data, and it’s a very interesting process that I thought I’d explain in a bit more detail because it’s something that you might want to consider doing yourself when you need to gather data.

We could have simply asked people how they use their tablets, of course, but we know that “self-report” data about how people do things is not as reliable as anonymous observations are. For one thing, people don’t always know how they do things and, when asked, may unknowingly change their behavior. And, unfortunately, we also know that when asked, people tend to tell you what they think you want to hear. So we decided to ask for help getting a lot of observations because we could get more observations this way and the observations would be far more diverse than anything we could do ourselves. (Thank you, field investigators!)

I’d like to discuss some other differences between surveys and crowdsourced observations so you can decide whether you might like to use crowdsourced observations for gathering data in your organization.

Surveys for gathering data

We often gather data inside organizations by surveying people. But surveys, of course, have their problems. Two big problems are lack of response from some people and response bias.

Most surveys don’t use random samples (because random sampling requires knowing how to do one and is time consuming and expensive). Not using a random sample introduces response bias, which means that we don’t know whether the people who did respond answered the same way as a random sample would have answered. But we also don’t know how the people who didn’t respond would have responded. Surveys pretty much ignore response bias because correcting for it requires surveying non-responders and analyzing the differences in answers between them and the people who did respond. And getting non-responders to respond is hard. (Duh.)

Even with random samples, some people are more willing to answer than others. For example, women are usually more willing to answer than men. And we know that some subgroups are more willing to answer than other subgroups are. Good survey researchers know their “population,” and then sample and weight the data accordingly to compensate for what they know about the population they are surveying.

All this is complex, so we typically just look for a large enough sample and hope for the best. But it’s important to realize that some questions, especially self-reporting questions, are notoriously unreliable. So if you are asking questions that you could observe instead, observe! You’ll have much better data!

Crowdsourcing for gathering data

Crowdsourcing data gathering allows you to have a group of participants (workers, customers, etc.) observe what is happening and send observations back to you. Actually, you can use crowdsourcing in research in a variety of ways, but I’m pointing out one of the ways you might consider using it.

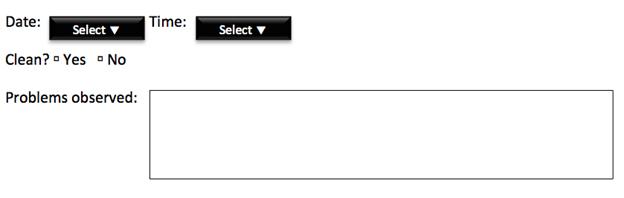

For example, let’s say you wanted to find out when the kitchens in your buildings most need cleaning. You could build a web form and ask people to fill it out whenever they use a kitchen. Or you could mount an iPad in each kitchen and post a form (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Survey Form: Is the kitchen clean?

This may be a silly example, but asking for real observations at the point of observation can be extremely valuable. (Having observers post observations later may force them to recall events, which suffers from some of the same problems as self-reporting does. People tend to miss things or embellish.) Many people have smartphones and tablets and if you post an easy-to-remember URL, people are often willing to post observations in a short form.

Using outside observers in research isn’t new. Citizen science (also known as crowdsourced science) is scientific research conducted with help from nonprofessional (avocational or public) scientists. For example, Cancer Research UK has recently launched an online interactive database of cancerous cell samples and is asking the public to help their lab researchers by looking at and spotting cancer cell cores in millions of images (www.clicktocure.net).

So consider crowdsourcing observations when you want to know what’s really going on. Make your observation form clear and concise. Consider how people will get those observations to you. Anonymous is best.

From the Editor: Want more?

At The eLearning Guild’s mLearnCon 2014 Mobile Learning Conference & Expo, Steven Hoober and Patti Shank will present Session 101, “How People Hold and Touch Their Mobile Devices.” In this session you will explore new research from The eLearning Guild that brings to light how people use all their different devices in all environments, from the street to the classroom. You will learn the research findings and synthesize them into actionable guidelines that you can use to immediately improve the design and development of your mLearning projects. You will leave this session with an understanding of how humans interface with touchscreen mobile devices, and how you can leverage this information in your mLearning design.