When jets take off from aircraft carriers, catapults throw them into the air so fast that they can fly the moment they leave the flight deck. We often think of training the same way. Let me explain.

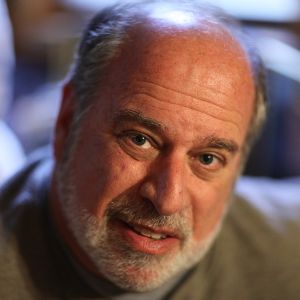

What we imagine happens vs. what actually happens

Figure 1: What we imagine vs. what is

real

Figure 1: What we imagine vs. what is

real

As illustrated in Figure 1, there is an assumption that training is the catapult that provides enough learning and support to launch someone right to proficiency and competence the moment they leave the classroom (line 1). If the training is great and the learners learn, we are told, they ought to be able to “fly” back at work and perform competently from day one. This is hardly ever the case.

Line 2 illustrates a more likely scenario. It’s easy and comforting to suggest that training leads directly to competence, but more likely, and only if done well, training leads to readiness. Competence, not to mention mastery, comes with time and experience. This important distinction goes to the heart of what happens after training. The realities of building competence are much more complex than just putting together a training program. Training can do a great job of getting people ready to be successful, but achieving and sustaining that success requires action beyond the course.

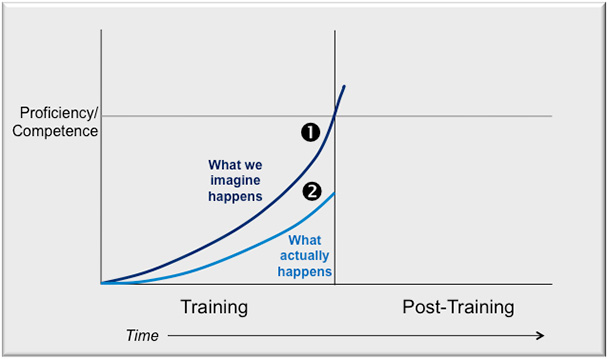

The easy way out

Figure 2: The easy way out: lower

the standards

Figure 2: The easy way out: lower

the standards

Some people might suggest that if we can’t get the learners to competence through training, our standards may be too high. In Figure 2, above, the proficiency/competence level was lowered so that it would seem that training accomplished its goal. Now there is likely a disparity between the training standards and the work standards, which is clearly not good! This is certainly the wrong way to go.

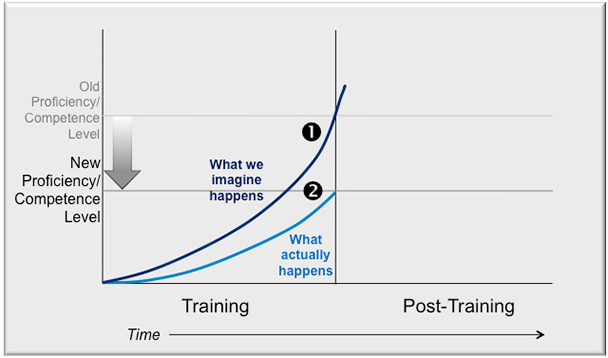

The risk of doing nothing

Figure 3: Why support after training

is important

Figure 3: Why support after training

is important

Line 3 represents the danger of abandoning learning support once the course has ended. Sure, some participants may get to competence under their own power, but many won’t. Without adequate learning support back on the job, the chance that performance will decline and the performer will crash, rather than improve, is too great. Furthermore, there is likely a tipping point where the decline in performance may become so pronounced and irreversible that you may have to start over. A very costly outcome, for sure.

The value of post-training support

Finally, line 4 in Figure 3 illustrates the tremendous leverage training gets when what is learned in the classroom (or online) is reinforced and supported in the workplace. This can include, but is not limited to:

- Getting front-line managers and supervisors involved in pro-active post training coaching.

- Enabling training participants to collaborate with each other through social networking and other means.

- Providing access to knowledge bases that contain valuable, accurate, rich, easy-to-find and easy-to-use information that supports workplace performance. This includes print and online documentation, presentations, best practices, and much, much more.

- Equipping workers with performance support tools (perhaps introduced in training) to make jobs easier and more productive.

- Redesigning the work itself to be more aligned with the processes and practices taught in training (or, redesigning the training to match the work; you’d be surprised how often this is overlooked), reducing any disconnect between the way things are taught and the way things are actually done.

Training no longer works in isolation. The transition from classroom (or an online experience) to the workplace must be seamless. This adds design decisions that transcend instruction. What will learners do after training? How will their new knowledge and skill be supported on the job? How should managers and supervisors be prepared to help their people after training? Do workers have the tools, resources and help they need to apply what they learned and be successful? No training program should be developed without also answering questions like these.

Achieving launch speed

The jet on the aircraft carrier has only a set amount of distance to travel on the flight deck before launch speed must be reached. The technology and costs behind this are extraordinarily high, primarily because the risks are even higher. Sure, we can launch everyone to assured and sustainable competence through training, but the cost and time is almost always prohibitive, and the efficacy of using training alone to accomplish this task is risky. So we need to rely on greater and better post-training support in the workplace. If we don’t, crashes are inevitable.