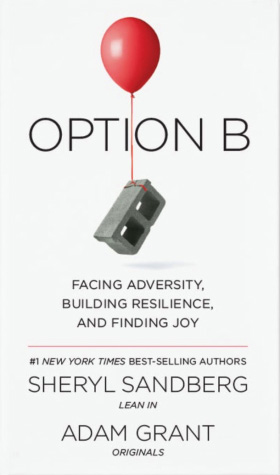

Business leaders can glean several important executive takeaways from Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s new best-seller, Option B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy. The book by Sandberg and co-author Adam Grant focuses on Sandberg’s reaction to the unexpected loss of her beloved husband, SurveyMonkey CEO Dave Goldberg, who died in 2015 at age 47 while the couple was vacationing in Mexico. However, there are several bona fide business lessons to be found within Sandberg’s heart-wrenching tale. These include:

- Building resilience

- The value of failure

- Supporting employees coping with loss

- Interacting with more sensitivity around a grieving co-worker

Book background

Much of the content in Option B comes directly from Sandberg’s journal. It candidly chronicles the young widow’s overwhelming grief in the blurry aftermath of the tragedy; her anguish for her children, who were age 7 and 10 at the time; and her thoughts on becoming a member of a club that no one wants to belong to.

Yet the book is not simply a teary personal memoir. It was co-written with Grant, a noted psychologist, author, and professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business. Grant helps contextualize Sandberg’s personal plight, contributing academic research and psychological insight about adversity, hardship, and resilience. Interspersed throughout the work are brave and inspiring tales of individuals around the world who managed to triumph over a wide variety of tragedies.

Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg (photo by Matt Albiani)

The book’s title is derived from an incident that occurred shortly after her husband died. Sandberg was lamenting that Goldberg would not be present at an upcoming father-child activity. Comforting Sandberg, her friend Phil said, “Option A is not available. So let’s just kick the shit out of Option B.”

Four executive takeaways from Option B

Business leaders can leverage some valuable lessons from Option B. Here are four executive takeaways:

Building resilience

Illness and death are inevitable setbacks in life. Yet businesses also suffer setbacks. Some, such as 9/11 or the recent financial crisis, might even be catastrophic. However, in life as well as business, resilience is the characteristic that makes it possible to recover and rebound. The importance of building resilience is a key thread running through Option B.

Sandberg defines resilience as the strength and speed of our response to adversity. “Tragedy does not have to be personal, pervasive, or permanent,” three Ps she repeatedly refers to in the book, “but resilience can be,” she writes.

“We all face challenges,” Sandberg notes in a video clip posted on Business Insider. “Some of them are big and huge and traumatic, and some of them are daily challenges. But we need resilience for all of it.” Grant expands on this concept, remarking, “We can’t control what happens to us. But we do have some influence over how we respond to the events and hardships in our lives.”

According to the authors, resilient organizations share some common traits. They place a high premium on personal responsibility, and they actively encourage employees to confront one another about problems that arise in the workplace. They value honest and open communication and are willing to engage in conversations that may be difficult.

As a Harvard-trained businesswoman who has also worked at Google, the US Treasury Department, and McKinsey & Company, Sandberg knows hard conversations can be uncomfortable. This is especially true when they concern employees who are not performing at their peak.

“A single sentence can make people more open to negative feedback,” Sandberg writes. She advises using positive phrasing such as: “I’m giving you these comments because I have very high expectations, and I know that you can reach them.”

The value of failure

The second executive takeaway from Option B concerns failure. Successful companies accept, acknowledge, and carefully scrutinize failure because they regard it as an important learning tool.

“At Facebook we recognize that to encourage people to take risks, we have to embrace and learn from failure,” Sandberg writes. She credits the military for teaching her the importance of creating a culture where failure is viewed as a learning opportunity. She shares an anecdote about a company field trip to a Marine base. She explains how Marines systematically debrief after every mission, publicly calling out mistakes made by individuals. At first, Sandberg found this practice harsh and even demoralizing, but she has come to realize its value.

“When done insensitively, debriefs feel like public flagellation, but when expected and required, they no longer feel personal,” she writes. She points out that the practice has become common in other verticals. “In hospitals, where decisions have life and death consequences, healthcare professionals hold morbidity and mortality conferences,” she writes, noting that this often leads to improvements in patient care.

According to the authors, resilient organizations create open cultures that actively encourage individuals to admit, and ultimately own, their missteps. “When it’s safe to talk about mistakes, people are more likely to report errors and less likely to make them,” they note.

Sandberg acknowledges that getting employees to embrace failure can be challenging. She shares a story about a co-worker at Google who used to bring a stuffed monkey named Whoops to her team’s weekly meetings.

“She would ask colleagues to share mistakes from that week, and then they’d all vote for the biggest screw-up,” she writes. “The winner got to keep the stuffed monkey on their desk where everyone could see it until the next week, when someone else earned the honor.”

Supporting employees coping with loss

Sandberg started a revolution with her 2013 book, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead. The landmark work shed a light on the plight of working women and sparked profound shifts in how modern companies view and value their female employees.

Her new book may have a similar impact on corporate America in terms of how it supports employees dealing with adversity. Option B is bound to initiate conversations that challenge, and ultimately change, the way companies help employees coping with loss.

“After the death of a loved one, only 60 percent of private sector workers get paid time off, and usually just a few days,” Sandberg writes. According to the authors, the corporate standard for paid leave is three days. Although Facebook actually had a more generous bereavement leave policy, Sandberg advocated to extend the policy following Goldberg’s death. Today, the Silicon Valley firm provides up to 20 paid bereavement days—twice what was previously offered.

The authors believe that increasing corporate bereavement support is not just a moral or compassionate imperative. There are bottom-line benefits to the practice. According to Grant’s statistics, grief-related losses in productivity in the United States alone may cost companies as much as $75 billion annually. The authors urge employers to re-evaluate their policies surrounding time off, flexible and reduced hours, and financial assistance for employees who are grieving.

“We need stronger social insurance policies and more family-friendly business practices to prevent tragedy from leading to more hardship,” Sandberg writes. She points out that compassionate firms will benefit by increasing loyalty among employees.

Interacting with more sensitivity around a grieving co-worker

While Sandberg advocates that companies offer longer bereavement policies, she notes that getting back to work is often beneficial for those who have suffered great losses. She recommends that co-workers treat them with care.

“Don’t automatically assume that the grieving individual wants to be coddled or relieved of their responsibilities. In doing so, you may contribute to them feeling totally useless, or may be denying them a much-needed process,” Sandberg writes. That said, she notes that a bereaved coworker may appreciate the support of colleagues who pick up the slack on an assignment, or demonstrate patience in the face of distracted or erratic behavior.

Tragedy often creates a paralyzing sense of awkwardness in the workplace. Although grief-stricken individuals require a lot of support and understanding, co-workers tend to either avoid them or politely ignore the elephant in the room. This can isolate the grieving employee, making them feel uncomfortable and increasing their suffering.

“As hard as it was to bring up Dave with friends, it seemed even more inappropriate at work. So I did not. And they did not. Most of my interactions felt cold, distant, stilted,” Sandberg recalls. Her boss, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, explained that co-workers did not know what to say to her.

Sandberg provides some suggestions. Instead of mundanely asking a work colleague who is dealing with emotional pain the banal question “How are you doing?,” Sandberg suggests saying instead, “How are you doing today?” This subtle change acknowledges the fact that they may be making incremental progress in their recovery. Additionally, it opens the door to a potential conversation if the grieving colleague wants to reach out.

Sandberg also encourages grieving employees to be honest about how they are feeling. “If someone asks, ‘How are you doing?,’ you don’t have to say ‘just fine’ if that’s not true,” Sandberg says. “Tell them you’re doing about as well as can be expected, or that you’re having a rough day.”

In conclusion

Despite its somewhat depressing subject matter, Option B is actually an optimistic book. It is a quick read, with interesting insights into how individuals and companies can cope more effectively with the inevitable pitfalls of life. There are valuable lessons that apply to everyone.

“In some way, we’re all living Option B,” Sandberg says. “The idea is how do we make the very most of it.”