I recently completed a project with a local government body that was combining the roles of two separate groups of employees into one. In their new role, the learners needed to know new methods as well as form new teams. Initially the job seemed straightforward, but things quickly became interesting.

It was a fascinating journey to take this local body and 60 of its employees through a project that resulted in the learners’ increased self-awareness and more consistent customer service. My original plan was to implement an eLearning solution; as you will see, the result was quite different: a blended program of learning that combined classroom instruction, field trips, a functioning knowledge base, and online communities of practice. You might even consider that some “social engineering” helped facilitate things.

What was unique about it was how we achieved this. Here is the story.

“Once upon a time …”

The organization saw learning as a discrete activity, separate from day-to-day work. Perhaps you’re working in one of those organizations, too. After the local authorities scoped and approved the project, they wanted to hire a trainer to do one-to-one training. The learners were the front-counter staff and the librarians in a rural government agency. All six of their service centers were in communities of 8,000 or fewer citizens. The combined front-counter staffs were to provide the contact point for citizens seeking to obtain services or other access to the local government.

Counter staff represented 18 diverse internal departments whose functions ranged from registering burials, dogs, and committee submissions to fixing roads and parks.

A recently completed survey indicated many managers didn’t think they had customers. This meant front-counter staff members struggled to get some of the departments to respond to customer requests and were sometimes unable to help customer resolution. Therefore, there was often a “them-and-us” attitude between departments and the counter staff members, which meant solutions for the customer could be fragmented, ambiguous, and slow.

I deduced a need for a substantial shift in service and the team culture. I considered that more interdependent relationships inside the organization would mean better customer care. It was a challenging task in an organization of many independent parts.

To achieve this, the methodology needed rigor to sustain not only new learning but also the subsequent supporting cultural changes.

The first plan and a reality check

The organization’s concept of learning was mostly traditional: classroom-based and single event. I wanted to change this paradigm and bring in eLearning, which I saw as an efficient solution for small isolated communities, since a key project deliverable was consistent service across all the centers. Fortunately, the project team was flexible enough to listen to my recommendations when they hired me. The project changed its learning approach from one-to-one knowledge transfer to a more rigorous methodology.

Isolated communities with online connectivity seemed a perfect solution. Unfortunately, this did not pass the idea stage, since the technology (IS) department wasn’t ready to support learning, saying “No” to privately accessing YouTube; even using Wordle was out. New technology was off-limits. This big disappointment at that early stage turned out to be a useful reality check.

Finding alternative solutions was frustrating but necessary.

The alternative: multiple methods

Research conducted by Michael Lombardo and Michael Eichinger for the Center for Creative Leadership (see References at the end of this article) suggest that the strongest learning comes from informal learning (70 percent), the next strongest from peer learning (20 percent), and then from formal courses (10 percent). I had wanted to use this 70-20-10 model, emphasizing the 70 percent on-the-job experiences, enhanced by web-enabled learning projects. Jay Cross has publicized how this model works in his writings on informal learning (again, see the References).

(Editor’s Note: Readers should take note of the caution advised by Don Clark regarding application of the 70-20-10 model, originally suggested by Lombardo and Eichinger and by the Center for Creative Leadership as a prescriptive guideline for developing managers. While the author made a carefully nuanced and successful application of the concept in this case, Clark’s comments are worth considering: “[S]ince [70-20-10] is a prescriptive remedy for developing managers to senior and executive positions, it does not mean that it is a useful model for developing skills in the daily learning and work flows that takes place within organizations, because it is being applied in an entirely different context than what it was designed for. Parts, or perhaps all, of 70-20-10 may be useful for developing professionals other than senior managers, but since the learning ratios vary greatly between various groups of learners [and even individual learners within a group], one has to be very careful about taking this approach.” See http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/media/70-20-10.html)

Howard Gardner’s “Multiple Intelligences” was also an influence. He outlines how learners need tools to use and material to interact with in many ways. Instead of using one way of learning, I thought using multiple methods to engage our semi-skilled, largely kinesthetic learners would mean deeper learning.

The project takes shape

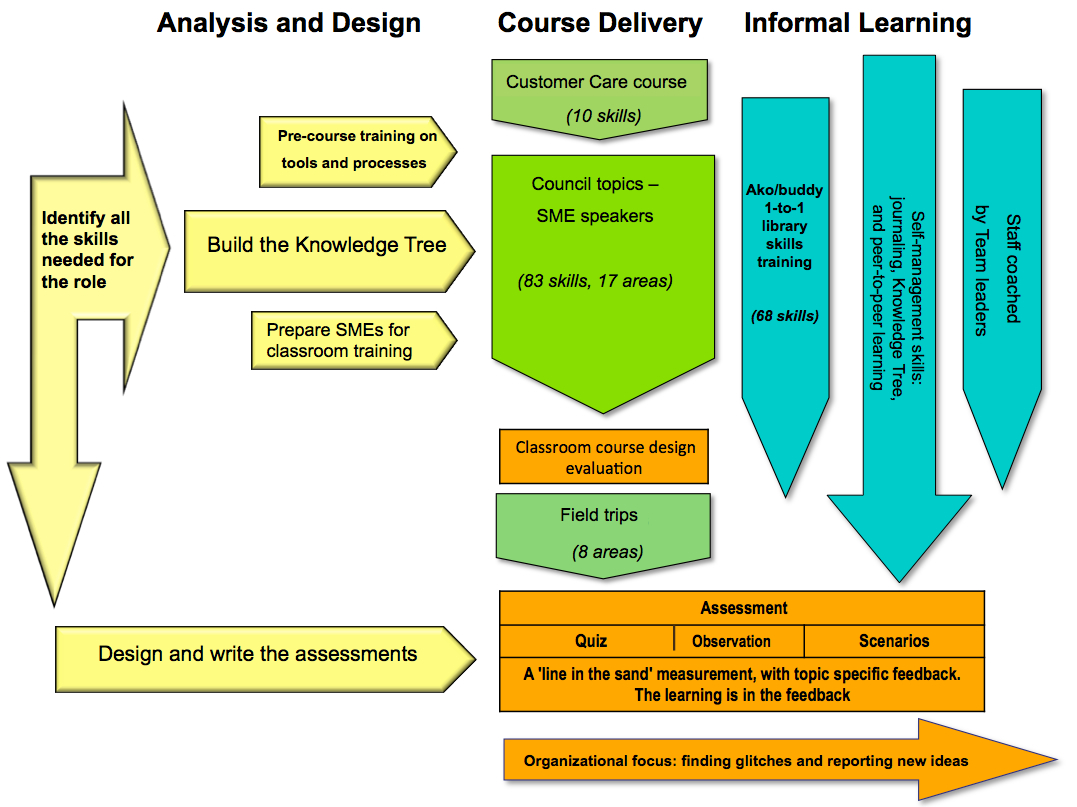

I outlined four stages for the learning part of the project: (a) analysis and design, (b) formal classroom delivery, (c) informal learning, and (d) return on investment (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Project stages

Analysis and design (the “yellow stage”)

I decided that forming new teams from geographically isolated centers in a multi-discipline organization would benefit from a consensus approach. DACUM works well for this purpose, so the team leaders were members of the focus group and I facilitated this analysis process. (Editor’s Note: DACUM is an acronym for developing a curriculum. It is an occupational analysis process for clearly defining the duties and tasks that expert workers perform.)

This process produced a basic skills list, containing 124 skills covering 18 distinct departmental roles and library functions. This list became a valuable learning tool and assessment guide.

Traditionally, a web-based information repository helps staff give correct information to customers. Since adapting existing tools was the only technology option, my first focus was the existing knowledge base, which was a pretty rudimentary and underwhelming resource. I thought this knowledge base, once it functioned properly, could be accessible technology, ensuring that the isolated service centers could give customers consistent quality service. It was the beginning of our diversified strategy.

While collecting the information the departments wanted in the knowledge base, two separate groups said to me, “Those girls (the counter staff) should know what they’re doing by now. Why do they still make mistakes?” This seemed an indicator of less-than-positive departmental relationships with counter staff

With one delegated staff member and an affable webmaster, in four months we re-built the skeleton of the existing knowledge base, called the Knowledge Tree. There were 200 pages. Nine months later, there are over 400. At the height of the project rollout, the top learners used it, on average, more than 64 times a day. This pragmatic multi-purpose tool worked well because it’s a business tool as well as a place to learn. It was the introduction to making learning an everyday activity.

Once the Knowledge Tree was functional and complete, we could see the impossibility of counter staff knowing everything; how could anyone retain all that? Each department saw only their own isolated knowledge components. Functioning in isolation, they had no reason to have a collective view of the organization.

The next task was to design assessments. (See Jane Bozarth’s article “Design Assessments First,” in the References.) I also wanted to show the client organization, which was new to L&D, that you could have a practical return on investment. At the same time, assessments would give the learners (the counter staff) a vehicle to show their competence to the department managers.

The three means of assessment were:

- Online quizzes

- Observational assessments

- Scenarios

The foundation of all of these elements was the basic-skills list developed earlier in the analysis stage.

All of the departments eventually signed off on their relevant skills on the basic skills list, the Knowledge Tree pages, and the assessment questions.

Course delivery (the “green stage”)

Two factors drove this learning stage: constraints on new technology, and the strained interdepartmental relationships. In the outlying areas away from the head office, few frontline staff members had contact with the departments. By running old-fashioned classroom courses, with departmental subject matter experts (SMEs) as speakers, the departments would have constructive conversations with our learners. Conversely, learners would get direct answers and build trust with the department SMEs.

We identified each department’s key staff members and asked them to present the skills our learners needed in order to represent them on a course that addressed the skills from the signed-off basic list.

These key staff speakers were crucial, and every organization I have been in has had them. You have them, too. They are the problem-solving “go-to” people. If you ask them an atypical question, most of the time they will know the answer. If they don’t, they’ll quickly find out and get back to you. They are pleasant to deal with. This modeled how we wanted staff to work with customers.

With great logistical difficulty—we had to keep the front counters operating—most learners completed the 18 courses. Counting all the times a learner was on a course, there were over 1,100 attendances. There were also field trips available to learners in this stage, building knowledge and solidarity across eight different areas.

Informal learning (the “blue stage”)

In the next learning stage, I introduced informal systems to support the traditional classroom events.

As the learning progressed through each of the centers, it was apparent that responsibility for learning was in the wrong place. Historically, in the dependent, top-down culture, counter staff could not show initiative. Shifting learners to change and take responsibility for both their learning and their actions was critical to project success. The needs analysis had not articulated this cultural factor. Changing this component became imperative before any future online communities of practice would work between the isolated communities.

I introduced the concept of self-management in a soft-skills course I designed and ran on customer service. The small section on self-awareness, where counter staff learned about their personal communication style, was usually the favorite part. Most had never learned about their preferences, or even realized they had communication preferences. This new self-awareness began scaffolding their self-management; now they knew their preferences and those of their team members, and had some understanding of adapting to other styles.

I also mentioned that, as a core part of the project, they were now in charge of their own learning. As a practical matter, this meant finding an average of 15 minutes daily learning time. They would each decide when and learn a topic they didn’t yet know, or work on an emergent skill.

They also received a package of support materials that included the basic skills list from the needs analysis. They were to use this list for self-assessing their individual skills for each upcoming course—both before and after the event. It was another tool for self-management.

I then described their key learning resources:

- The knowledge base—to learn new/less familiar topics

- A training database—for practicing the software system

- Departmental course speakers—to clarify or request more details

- Fifteen minutes learning time—to build learning habits and write about them

- The basic skills list—to find and narrow any skill gaps

- Their peers, ako/buddy and team leader/coach—to give and consolidate learning (Editor’s Note: “ako” is a Maori term that refers to a reciprocal teaching/learning relationship; there is not an exact equivalent term in English)

There were two journals in the package. One of them was for recording what they learned. The learning journal became a pivotal tool.

They would write up in the journal what they’d learned in their 15 minutes. The informal learning now built on the formal courses and field trips. My early preference was for them to write online as a shared formative learning tool, but instead this handwritten journal was the nexus to reflective practice.

Some curious learners began writing immediately. Styles vary—from works of art through three-word bullet points to daily streams of consciousness. The journals are as unique as each learner.

Journaling was the most difficult learning component. Work is not a place where they previously had time to pause and consider how they worked or learned—or its implications.

Some learners struggled, needing more support. Using headings in the journal such as “What I learned today” helped. Motivational emails, sending examples of bloggers’ self-reflective practice, putting up posters, and plain old talking face-to-face were ways I inspired—and dealt with resistance.

Only three staff members refused to journal, complaining to senior managers, the HR advisor, and union representatives. This greatly influenced staff negativity.

It would have been easy to ignore these few. However, as a project team we kept backing each other, sticking to our agreed processes, and, while supporting staff, stayed focused on future results. Although extraordinarily difficult at times, this worked.

Simultaneously, I taught and coached the team leaders in basic coaching skills. Each learner had personal coaching time with their team leader, bringing their journals. The writing helped begin meaningful, regular coaching conversations.

Coaching and journaling together have been successful. Staff members now use reflective processes, telling me journaling builds confidence—they write independently simply because it is useful.

Visible ROI: The assessments (the “orange stage”)

Learners contact me when they’re ready to do assessments. The online quizzes, designed to be fun and take only 10 to 15 minutes, boost their confidence. Quirky answers in multiple-choice questions have them smiling. Quizzes also bring personal accountability. Although few staff members achieve 100 percent, they enjoy learning through the feedback conversation because I ensure it’s positive.

On an organizational level, quizzes have highlighted mistakes in areas where we had assumed competence. These would have gone undetected without this formative measure.

The behavioral and scenario assessments take place before final commendation.

Using Peter Senge’s version of the learning organization and interpreting his systems thinking into this environment has meant learners now document new ideas and glitches. The learners’ naïve enquiry brings fresh perspectives to existing systems. By documenting these, learners win movie tickets, and the organization wins with better processes.

Conclusion

Despite meeting obstacles that are typical in complex change projects such as this, I was pleased with the outcome, namely that staff members are now able to:

- Perform front counter and library skills competently

- Use online tools and reflective practices

- Self-manage learning

- Work more cohesively as positive teams

- Contribute ideas and fix glitches, benefiting the whole organization

With limited access to technology, the learning model changed to multiple learning modes, becoming prerequisite skills for technology-enabled learning. Learners first needed to have self-management skills before they reached the stage Harold Jarche describes, where “Work is the learning, and learning is the work.” Staff members now have more options and learning methods they can use.

Significantly, internal customer conversations have better problem-solving outcomes, and external customers report service has improved.

References

Bozarth, Jane. “Nuts and Bolts: Design Assessments First.” Learning Solutions Magazine. 3 April 2013. http://www.learningsolutionsmag.com/articles/1146/nuts-and-bolts-design-assessments-first

Center for Creative Leadership. “The 70-20-10 Rule.” Leading

Effectively e-Newsletter. 2011.

http://www.ccl.org/leadership/enewsletter/2011/NOVrule.aspx

Cross, Jay. Informal Learning: Rediscovering the Natural Pathways That Inspire Innovation and Performance. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer, 2007.

Cross, Jay. “What’s informal

learning? (in under 3 minutes).” Jay Cross blog. 22 June 2012.

http://www.jaycross.com/wp/2012/06/whats-informal-learning-in-under-3-minutes/

Gardner, H. Multiple Intelligences: The Theory In Practice. New York: BasicBooks, 1993.

Jarche, Harold. “Work is learning and learning is the work.” Life in perpetual Beta (blog). 17 June 2012.

http://www.jarche.com/2012/06/work-is-learning-and-learning-is-the-work/

Lombardo, Michael M. and Robert W. Eichinger. The Career Architect Development Planner, 1st ed. Minneapolis: Lominger, 1996.

Senge, Peter. The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization. New York: Crown Business, 1994.

Smith, Mark K. (2001). “Peter Senge and the Learning

Organization.” infed. 2001.

http://infed.org/mobi/peter-senge-and-the-learning-organization/.