“If

there is no struggle, there is no progress.”

—Frederick Douglass

You’ve all heard this old joke: A lost and beleaguered tourist in New York City stops a local pedestrian on the street and asks, “How do I get to Carnegie Hall?” “Easy,” replies the local. “Practice.”

Let’s ask a similar question, “How do you get to high performance?” Again, practice is an essential part of the answer. We can point to proven instructional design principles, but sometimes our best intent gets lost in the weeds of complex learning strategies that we have no time, resources, or understanding to apply or test fully. In our efforts to improve performance in a verifiable and sustainable way, many of us would benefit by some simple rules and techniques for using practice to make learning stick.

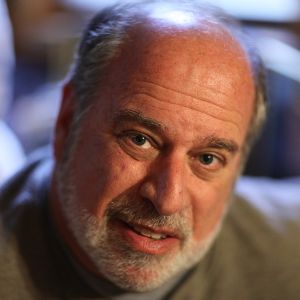

Enter Daniel Coyle, a keynote speaker at last month’s eLearning Guild’s Learning Solutions Conference. Coyle, a sportswriter by profession, has been studying what it takes to be an outstanding performer. He draws from research and observation in a number of fields beyond sports, including business and the arts, to make these principles come to life.

Three habits

Coyle’s sports orientation yields some keen insight into one of the most important aspects of learning in any endeavor—practice. To do this, Coyle suggests focusing on what he calls the three habits.

Habit 1: Maximize “reachfulness”

Coyle recommends that practice should be difficult; it should stretch the performer. Combined with repetition, a high level of engagement, actions that have purpose, and swift feedback, practice can be an intensely powerful learning tool. Forget passive learning, Coyle says; make it all-involving and just a tad out of reach.

Habit 2: Fill the windshield

People who aspire to great performance, says Coyle, need to see “stars,” the high-performing role models they want to emulate. They should be encouraged to “steal” the techniques of masters and make them their own. Finally, it is important to focus on mistakes, not to penalize, but to celebrate and learn from. A “mistake club” can be a fabulous learning experience.

Habit 3: Communicate like a coach

Finally, when teaching new skills, communicate like a coach. Coyle notes the criticality of trust between learner and instructor and that trusting connections establish themselves early. Speeches (or, in our world, lectures) are far less effective than sending what he calls VCIs—vivid, concise images—to individuals. Finally, like all great coaches do, praise for effort, not ability. Continuous progress and support helps one obtain mastery far better than grades.

Coyle’s books

Coyle’s book The Talent Code provides the basis for understanding how typical performers become great performers. Sure, there is the obligatory (yet interesting) chapter on how the brain works, but, for the most part, the focus is on real, practical ideas and suggestions.

His other book, The Little Book of Talent, should sit right next to everyone who seeks to develop learning solutions that work. This book, and it is little, has 52 tips for improving skills. Each is brief, to the point, practice-focused, and eminently useful. The tips are divided into three groups: 1) Getting Started: Share, steal, and be willing to be stupid; 2) Improving Skills: Find the sweet spot, then reach; and 3) Sustaining Progress: Embrace repetition, cultivate grit, and keep big goals secret. Some examples include be willing to be stupid (tip #5), embrace struggle (tip #17), pay attention immediately after you make a mistake (tip #22), embrace repetition (tip #43), and, to learn more deeply, teach it (tip #47).

Implications for our work

What should be clear to us is that Coyle’s three habits really are nothing new. Rather, they are similar to what top thinkers in the learning and performance field have been saying for decades (think Gagne’s “Events of Instruction,” or Gilbert’s “Performance Engineering,” for example). But Coyle showcases principles of practice and mastery in a real and simpler way.

Intrigued? I certainly was. The more I read these tips, the more I came to the realization of how much obvious sense they all made. There are important lessons here about the art and science of practice and the ways people actually reach mastery. If you look at Coyle’s work and feel the same way, then all you have to do is plant these ideas into your programs and watch your learners grow.

Early in my career, we built a course that began with an intense simulation, designed so that most participants would initially fail. From this, a critical learning moment would emerge and then, through practice not unlike what Daniel Coyle is suggesting, the road to mastery would be clear and achievable. But to those in charge, this was unacceptable. “We have a culture in this company of success, not failure,” they told me. “Fix the simulation so that everyone succeeds.” I tried to dissuade them, but to no avail. You can imagine the result. Don’t go down the same road.

Learn more about Daniel Coyle and his books here and here.