The learning and development world has seen a much-needed focus on designing for marginalized populations in the past few years, both in terms of accessibility and in terms of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). But one area that hasn’t gotten much attention–and particularly not much from the perspective of the communities in question–is the topic of neurodivergence.

Understanding inclusion from a neurodiversity perspective has both a DEI component (addressed in this article), and an accessibility component (addressed in the two articles to come in this series). As learning and development professionals, applying both is not just about accommodating impairment or staying compliant with the ADA. It’s about unlocking the talents that diverse neurotypes bring.

Positives of neurodivergence

One of the best things you can do to lead to greater acceptance of neurodivergence in the workplace is to learn and reinforce to others that neurodivergent brains are often different in positive ways, despite broad negative sterotypes. Here are some examples, but remember, not all traits apply to all individuals; if you know one neurodivergent, you know one neurodivergent.

Autistics often have an increased capacity for lateral and creative thinking. We may have great attention to detail and can absorb ourselves deeply in our work. Our special interests can lead to great expertise in our chosen topics. We tend to have excellent memories. We’re often tenacious and resilient. We tend to be excellent at direct communication. And we’re usually extremely fair-minded and fierce advocates of equality.

ADHD-ers have a great potential for in-depth study and work when hyperfocused. We’re often witty, creative, and social. We have gifts of spontaneity and generosity, and like our autistic neurokin, we can be extremely resilient. We tend to be deeply compassionate and fair, and excel at motivating others with our high energy.

You might have already encountered some new words and phrases, so before we go too deep, let’s establish some fundamental knowledge about neurodiversity.

The basics

The concepts of neurodiversity and neurodivergence aren’t clinical ones. They arose from the autistic advocacy community in the late nineties, and they didn’t even appear in the Oxford English Dictionary until a few years ago.

Here they are, on the June 2019 New Words List, nestled snugly between meeple and noob. (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: The Basics

There is no “official” list of divergent neurotypes; the most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) doesn’t recognize the term. However, other than autism and ADHD, neurodivergence includes some learning disorders (dyslexia, dyscalculia, and dyspraxia); neurotypes caused by trauma including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), complex post-traumatic stress disorder (c-PTSD, which is not recognized by the DSM-5), and traumatic brain injury (TBI); as well as some that are related to personality. Neurotypes are separate from mental illnesses, such as anxiety, depression, and eating disorders.

These articles will primarily cover autism and ADHD, for a few reasons:

- First, the concept of neurodivergence is most closely associated with autism and ADHD.

- Second, covering all divergent neurotypes is a huge task requiring an incredible amount of expertise, particularly in the realm of learning disabilities, and it would be a disservice for me to try to cover those topics without that expertise… although I’d love to learn from an expert who’s willing to pick up the task!

- Finally, and of tremendous importance to me: There is a phrase in the disability advocacy community: “Nothing about us, without us.” It represents a belief that the best people to educate about disabilities are the people from those communities, and autism and ADHD are neurotypes I can represent from my own experience.

And as this article focuses on DEI, and autism is the neurotype that has more stigma attached to it, this article necessarily focuses more on autism than ADHD.

Language

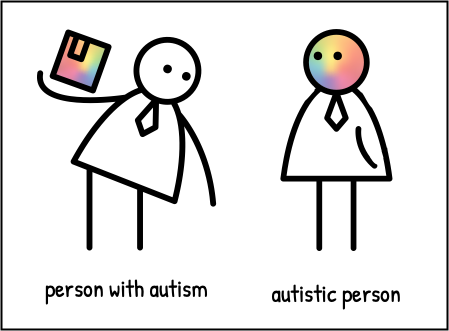

While many disability communities embrace person-first language, autistics generally prefer identity-first language instead. This preference isn’t universal, so always defer to someone’s expressed preference; however, when speaking or writing for a general audience, it’s helpful to know that most surveys have indicated about an 80% preference for identity-first language among autistics.

Here are the two approaches in action (Figure 2):

Person-first language (non-preferred):

- This course is designed to accommodate learners with autism.

- Workers who have autism may have hidden needs that are easy to accommodate when you know about them.

Identity-first language (preferred):

- This course is designed to accommodate autistic learners.

- Autistics generally prefer identity-first language.

- As an autist, I believe that my neurotype cannot be separated from my identity. (Autist isn’t fundamentally different from autistic; it’s just a preference.)

Figure 2: Person-first language vs Identity-first language

If it seems jarring to refer to someone as an autistic, please consider the following:

- That feeling may be because society associates negative traits with autism. However, many autistics reject these associations and view our neurotype with pride.

- That feeling may be because many consider person-first language to be more humane and respectful. Autistics who prefer identity-first language would counter that the first step in acknowledging someone’s humanity is to respect our language preferences.

Here are some other phrases to avoid.

“a little bit autistic”

This phrase is problematic for many reasons, including that it often represents an improper understanding of the autism spectrum, that it’s similar to the functioning labels that many autistics consider inadequate and harmful, and that it’s often used euphemistically to reinforce harmful stereotypes.

If you do see yourself in descriptions of autism, it might be helpful to know that autism and ADHD have a wide range of overlapping traits… as do autism and trauma. And, of course, it is possible to have traits in common with autistics without being neurodivergent at all, particularly if those traits don’t disrupt your quality of life or work.

The other possibility, of course, is that someone is not “a little bit” autistic… they’re autistic. Due to dramatic changes in the understanding of autism over the past three decades, more and more neurodivergence is identified in childhood, but it’s very possible to go undiagnosed until adulthood… or to never get diagnosed at all. This is particularly true with women, girls, racial and ethnic minorities, and those in under-resourced communities, for the following reasons: 1) the diagnostic criteria is based on typical presentations in young, white boys, and others may present differently, 2) autistic traits are often interpreted differently when marginalized individuals display “typical” neurodivergent traits, and 3) diagnostic resources aren’t as readily available for marginalized populations.

“on the spectrum”

While the word “spectrum” is part of the name of the clinical diagnosis (ASD stands for autism spectrum disorder), the concept of the spectrum is widely misunderstood. There are many articles on the internet that explain why, but the best rule is that if you don’t specifically know how it’s misunderstood, or you’re using “on the spectrum” as a euphemism, just use “autistic” instead.

“Asperger’s”/”aspies”

Asperger’s Syndrome is no longer a clinical diagnosis. In addition, many autistics object to the use of the name for historical reasons. (Hans Asperger was a member of the Nazi party and, while specifics cannot be fully known, his work likely involved inhumane treatment and even extermination of autistic children.) Many do still use the term because they were diagnosed when it was still in clinical use, and it’s not for me or anyone to correct them. But again, it shouldn’t be used as a euphemism or as a de facto functioning label.

“normal”

The proper word for non-neurodivergent individuals is “neurotypical”. Non-autistics are known as “alltistics”.

“high-functioning/low-functioning”

Functioning labels are related to the misunderstanding of the spectrum. These labels ignore the reality that each autistic has a collection of autistic traits, each of which can affect their life and work a little, a lot, or somewhere in between.

It also ignores the fact that many autistics put a great deal of effort into masking, or presenting themselves as neurotypical, and that effort takes a tremendous, often unseen toll. As comedian and autistic Hannah Gadsby says, “I have what’s called high-functioning autism, which is a terrible name because it gives the impression that I function highly. I do not.”

When someone uses functioning labels, they’re usually trying to send a message, so autistics recommend simply using those specifics instead, with something like, “He is autistic and non-speaking,” or “I am autistic and don’t have significant support needs.”

Visuals

Puzzle pieces and the color blue

When representing neurodivergence and autism specifically, avoid using puzzle pieces and the color blue. They are closely aligned with the branding of Autism Speaks, an organization that many autistics consider a hate group due to their focus on finding a “cure”, their support of Applied Behavior Analysis (which many autistics consider abusive), and their lack of autistic representation within their organization.

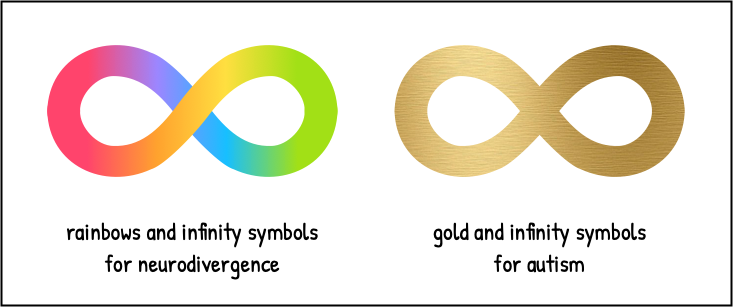

Instead, use rainbows and infinity symbols to represent neurodivergence, or gold and infinity symbols to represent autism specifically. (Figure 3)

Figure 3: Use of symbols

Images and other graphics

Because neurodivergence is a hidden disability, it can’t be visually represented the way that some disabilities can. However, you can normalize neurodivergent accommodations by using visuals of people managing their sensory inputs using headphones or dark glasses, or using sensory toys or stim toys such as fidget spinners.

Social interactions

“they might be autistic”

Don’t speculate that someone is neurodivergent. It’s rude, it’s a violation of their privacy, and it’s often coupled with…

using neurodivergence as a shorthand for negative traits

It’s all too common to hear phrases like, “they’re autistic and they just don’t interact well with people,” or “they’re neurodivergent and they didn’t get the joke.” These phrases reinforce stereotypes that are harmful and often inaccurate. If it doesn’t make sense why this is offensive, replace “neurodivergent” with a marginalized race, nationality, or gender, and it might be more clear.

“you don’t look/seem autistic”

No neurotype has an effect on appearance, and remember, many neurodivergents work hard to “mask” some of their traits for social or professional acceptance, despite being proud of our neurotype. Regardless of intent, this comment will not come off as well-informed or kind.

Conclusion

You’ve taken the first step toward building a more inclusive workplace for neurodiversity by learning about the positives of neurodivergence and how to represent divergent neurotypes more authentically. Applying that knowledge will help you clear away some of the barriers to neurodivergents working, learning, and contributing in your organization. In upcoming articles, we will cover how you can design learning experiences to be more neurodivergence-friendly… and better accommodate a variety of other needs at the same time.

This is a huge topic and I would love to entertain questions… or, if you’re neurodivergent, feel free to send suggestions for the coming articles on designing learning experiences! Just comment below or contact me on Twitter at @jdyktz.

Editor’s Note: This article represents the opinions of the author, and does not reflect the opinions of Learning Solutions, Focus Zone Media, or their respective parent companies. Please consult an appropriate professional for guidance or questions concerning ASD or ADHD.