In “L&D Must Resolve 'Content Chaos' to Meet Performance Goals,” we identified several challenges L&D departments are currently facing, with the aim of addressing three of those key challenges with action-oriented solutions. In this article, we delve further into competency, capability, and skills frameworks; the attempt to assign the right training and development courses to the right employee; as well as the gaps between these frameworks and actual capability, performance, and business outcomes.

Competency frameworks, capability frameworks, and now skills frameworks entice us with the promise of achieving performance improvement—in part through real and valuable personalization for each employee. These frameworks are a well-intended attempt to provide a structure, through an L&D lens, that enables us to map out an organization so that we can assign the right training and development courses to the right employee and accomplish up- and reskilling, ideally at scale.

It's a nice idea. Yet in practice, the impact of these frameworks on personalization and performance is somewhat questionable. Combined with navigating the complexity that surrounds their use and questions about how to define what a useful and usable framework is and how and where to apply them, you have a challenge on your hands.

Distinguishing competency, capability, and skills

To help us in the present, let’s start by defining competency, capability, and skills and identifying the differences between them.

Competency models

The CIPD defines competencies as “broader concepts that cover demonstrable performance outputs as well as behavioral inputs. They may relate to a system or set of minimum standards needed to perform effectively at work.”

Competency models and frameworks have long been used as tools aimed at assessing talent and identifying performance and development needs. However, they have been much maligned through the challenges they also present—the time and cost to develop, their applicability and usability (or lack of) so far in practice, their lacking flexibility to change, and, as we raised in our previous article, lack of consideration for social and organizational learning.

An even greater challenge is both agreement on what defines a competency and the definitions of the competencies contained within a particular model. Consider the lack of alignment regarding job descriptions across roles, both within an organization internally and across organizations externally: For example, sales executive, account manager, and customer success manager are titles often used to describe the same job and tasks.

However, agreement in definitions of roles and competencies is critical in order for an organization to utilize a range of sources, including providers whose definitions vary; in the absence of such consistency, some agreement on conversions from one framework to the next is needed.

Capability frameworks

Capability frameworks were developed, in part, to address rapid change, expected more so in the future. Nevertheless, their definitions are often entirely interchangeable with those for competency frameworks. Sadly, this means these frameworks can often be found gathering dust on a virtual shelf, due to lack of regular reviews and updates, poor implementation, a complex language that is not user-centered, and the resulting lack of employee and stakeholder buy-in.

Skills frameworks

Now we are seeing the burgeoning growth of skills frameworks, adding what feels like evermore complexity and confusion. Yet, skills are vital to an organization’s success and performance, and can be directly connected to Human Capital Theory (Becker, 1962) and the Resource-Based View of Strategy (Barney, 1991).

In essence, these look at the knowledge, skills, and ability contained in an organization and how they are used to deliver performance—and these are the organization’s key differentiators. As the Great Resignation underscored, human capital can simply walk out of the hybrid door, never to return. Hence, skills measurement, management, and development have become key strategic preoccupations within organizations.

How skills and competency frameworks differ

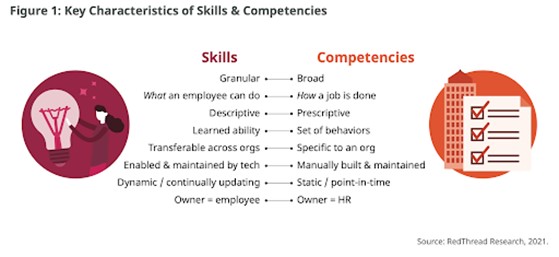

How then do skills frameworks differ from competency frameworks? Research by RedThread identifies key characteristics of skills and competencies and highlights the confusion experienced by employees and business leaders: “They don’t care about the differences, they simply want to know what’s expected of them.” In other words, what constitutes performance.

Definitions from the SFIA Foundation add more clarity and granularity:

- Knowledge describes facts and information typically acquired through experience or education. An individual can acquire knowledge without applying that knowledge.

- Skill is applying knowledge and developing proficiency—which could be done in a controlled environment, such as an educational institution, through, for example, simulations or substantial project work.

- Competency is applying the necessary knowledge and skill in a real-world environment with full professional responsibility and accountability for one's own actions. Experience in a professional working environment represents the difference between demonstrated skill and demonstrated competency.

Key differentiators of skills frameworks, according to RedThread’s research, are that they are “enabled & maintained by tech” and are “transferable across orgs.” However, the reality is far more complicated, due to an even greater and ever-growing conundrum: What constitutes a skill? And what can be deemed a valid and reliable assessment of those skills?

The current situation is one where multiple frameworks, skill levels, and assessments are available or in development from vendors, governments, and other bodies. For organizations and their employees, deemed proficiency against one skills framework or assessment might mean something completely different in another, reducing their transferability. Let’s look at these challenges in practice.

Skills and personalization in practice

We previously discussed how learning pathways have been offered as a solution to personalization; where skills are concerned, learning pathways and the content contained in them can be tagged by skills and thus allocated to employees. However, this too presents us with accurate performance gap analysis challenges.

Currently, the primary method of identifying an employee’s acquired skills is via self assessment, possibly with input from manager or peers, and/or inferring the employee’s skills from other data sources, such as their CV, LinkedIn profile, or HRIS records. From this data, the employee will be prescribed tailored pathways. The questions remain: How accurate is this process? How well does it link to performance?

There are several limitations to this ‘solution’: It is subjective. It doesn’t confirm what a person can do in a consistent and reliable way. It looks at ability levels of separate skills, rather than the whole person and their full range of ability. And, last but not least, we are notoriously bad at self-evaluation, even when trying to be as honest as possible. Any skills inferred from CVs and LinkedIn depend upon the quality of data in those sources, making it basically impossible to verify this accuracy.

While having some data may be better than no data at all, if we are making an investment of time and resources and asking our employees to do the same, can we honestly say this is a viable solution? Moreover, if we are making key workforce decisions, based on performance data, more objectivity is a necessity, especially if we are to avoid litigation risk.

To illustrate this, let’s look at a typical and real scenario facing our employees: For example, I wish to develop my proficiency in data analysis. I select that skill, self-assessing at level 3 on a scale of 1 to 8 (note that assessments vary both in their proficiency levels and descriptions and are usually non-configurable). I set myself a goal to develop to level 5. I am then presented with learning content and pathways that have been tagged for this skill.

Yet, how do I know the content is helping me to progress my proficiency and performance from level 3 to level 5? The simple answer is that I don’t. While on the surface, the training appears personalized, in reality, it is one-size-fits all, delivered to anyone who self-assessed at level 3. And with such subjectivity, we’re beginning to create a skills and content labyrinth, all without a focus on tangible, work-related performance needs.

We question the potential risk of adding more confusion and overwhelm for our employees, by throwing a mapped library and set of skills at them without a clear performance benefit. This is significantly important when, as Guild Masters Michael Allen, Conrad Gottfredson, Bob Mosher, Clark Quinn, Don Taylor, and Will Thalheimer all generally point out in 2022 in Review: Guild Masters Look Back, the shift is toward performance—improving performance and its impact on the business.

Overcoming the challenges

In seeking to overcome some of these challenges or understanding what to consider when establishing a useful and usable skills framework, the limitations of such a framework, and how to maintain focus on performance, we suggest starting with two key considerations:

- Much of this is uncharted territory. The growth in the use of AI and data in skills and talent is perhaps the biggest shift in people development since the introduction of technology into people processes. Any technology investments necessitate rigorous planning, use-case tests, cost/benefit analysis and assessment.

- This is by no means the remit of L&D alone. It is an organizational, system-wide responsibility. Without the collaboration across human resources and organizational development, as well as IT, your stakeholders, and the employees themselves, it is highly unlikely to be successful.

As Harold Jarche points out, referring to Senge’s The Fifth Discipline, “The four disciplines of Personal Mastery, Mental Models, Shared Vision, and Team Learning must be in place before Systems Thinking can unify them. All of these disciplines are about learning—individually, as teams, and as an organization. Senge described Systems Thinking as, ‘a very deep and persistent commitment to ‘real learning.’”

So how do we approach this challenge?

- For the organization, it requires robust change management, organizational development, organizational design, employee experience, communications and engagement, data strategy, and governance. This is, of course, even more significant for large and complex entities.

- For practitioners, this means being comfortable with ambiguity, not having all of the answers up front; a mindset toward experimentation and learning from reflective, evidence-based practice.

The critical starting point is identifying where the use of a skills-based approach can make a difference to your organization’s performance—in essence, use cases.

- For L&D, this is most likely linked to a key strategic initiative, perhaps a new market or product development driving areas where the organization wishes to grow or where it lacks capability.

- For talent, this might be a particular process where the use of skills helps make data-informed decisions, saving time and cost.

However, as Guy W. Wallace points out, this requires measures on both effectiveness and efficiency. Linking back to evidence-based practice, choosing one use case or area to focus on and learning from this is paramount; this is not about boiling the ocean. Think big, hence the focus on this being a system wide approach with a long-term view, but start small—go slower to go faster.

You most probably have job profiles and competency or capability frameworks readily available in your organization. Harvest what you already have, and assess what is still used, usable, and can be repurposed, keeping your focus on the performance needs and your unique context. Assess recruitment data for insights on where hires have been rejected because they didn’t have required skills and where and why there are open, unfilled positions.

Next, identify which skills are unique to your organization and which are more generic. Define the proficiency and outcomes required for the desired performance to achieve strategic goals. This then informs your governance, data, learning strategy, and approach.

Finally, craft a unified framework by assessing performance needs and combining your existing content with the unique and generic skills you have identified, while applying design and governance principles.

The steps in the attached resource, "How to Implement Your Skills Framework & Keep Performance at the Epicenter," can help you get started.

Explore AI in L&D—and more

Having looked at performance improvement and development from an organizational, high-level view, we will shift our focus to the other end of the spectrum in our next article. We will look at individual learners and the teams within which they perform. We will also look at workflow learning, how to find answers to questions quickly and efficiently, and improved functionality through AI contextualization engines and mapping capabilities. In-depth content on each of these topics will appear in Learning Solutions Magazine in the coming months.

Meanwhile, register for for the winter Learning Leaders Online Forum to learn from experts, network with peers, and explore emerging issues. The Forum opens with Markus Bernhardt's talk on the role of AI in the future of L&D. And consider joining the Learning Leaders Alliance, a vendor-neutral global community for learning leaders who want to stay ahead of the curve.