Bridging the gap between educator and learner can be highly gratifying. When you get it right, the signs are everywhere – your learners are engaged with your materials from the beginning, test scores are high, and most importantly, retention and performance are measurably improved for weeks and months after the learning activity has been completed.

Editor’s Note: Parts of this article may not format well on smartphones and smaller mobile devices. We recommend viewing on larger screens.

When you get it wrong, the signs are painfully clear, but the reasons may not always be obvious. Whether you are building activities conventionally or online (e-Learning), the road can be fraught with peril if you are not mindful of the hazards along the way. Making that all-important connection with your learners does not happen by accident. There are fundamental principles you can easily miss.

On the following pages you will discover 12 principles to guide educators when developing learning activities. Applying these principles and the helpful insights suggested with each, will help avoid the hazards that can appear after content publication.

Principle #1: Attention and engagement are not mutually exclusive.

What message does the billboard convey to you?

If you were driving by this billboard at 60 mph, how would you parse the message? Some drivers might perceive this message to be: “Stop Rampy Chevrolet. Now!” Is this the intended message? Probably not. Does it achieve the desired effect (to sell Chevrolets)? Probably not. What’s missing?

Attention, engagement, distraction and boredom

No one wants to be boring. And no educator wants their materials to be dull. In e-Learning, it is all too easy to be seduced into using “eye-popping graphics” and superfluous media in the effort to be more exciting and to prevent boredom. But this temptation to demand attention often comes at the expense of engagement and learning. All the eye-popping graphics in your learning materials are not capturing Johnny’s attention.

What is attention?

John Dewey was an educator and prolific author in the early and mid-20th century. Dewey defined attention in a learning environment as “the unity of the action of the mind.” He observed that true attention is achieved when the learner brings three vital elements to the task at hand:

- TO WHAT: a degree of heightened focus, and:

- FOR WHAT: a sense of purpose – the anticipation of something (of measurable benefit) coming in the future, and:

- WITH WHAT: a connection of the learning activity with the learner’s past experience.

A lesson from advertising

Think about your first encounter with the billboard you saw earlier.

- Did it get your attention? (Maybe)

- Did you anticipate a benefit ? (Probably not)

- Did you associate some part of your own experience with the message? (Not likely)

What’s true in advertising is also true in e-Learning.

Demanding attention is not enough

You cannot demand attention any more than you can persuade someone to buy something they don’t want.

Edward Tufte is a contemporary author on information design and data integrity. In 2003, he wrote an article for Wired Magazine, railing against, among other things, the alarming emphasis of style over substance in PowerPoint presentations. In this article he made a similar case about attention and learning when he said: “Audience boredom is usually a content failure, not a decoration failure.”

There is nothing inherently wrong with using compelling imagery and media in your learning materials as long as they augment your message with substance rather than distract with irrelevant “eye-candy.”

Attention without engagement is merely distraction.

Principle #2: The learning environment must be conducive to experimentation

Lorna was terrified. While taking an important quiz, she encountered a challenging question. Most of the possible answers seemed correct – or close to it. She was immobilized with indecision. She pondered the question far too long. Just before her time ran out, she held her breath for a moment, took her best guess at the answer, then clicked the submit button. If only she could have tried out her answer first.

Learning can be cultivated in an environment which is physically comfortable, non-threatening, and supportive of experimentation and discovery. With e-Learning, you have a handful of ways to provide safe, exploratory “guess and check” opportunities in your learning materials.

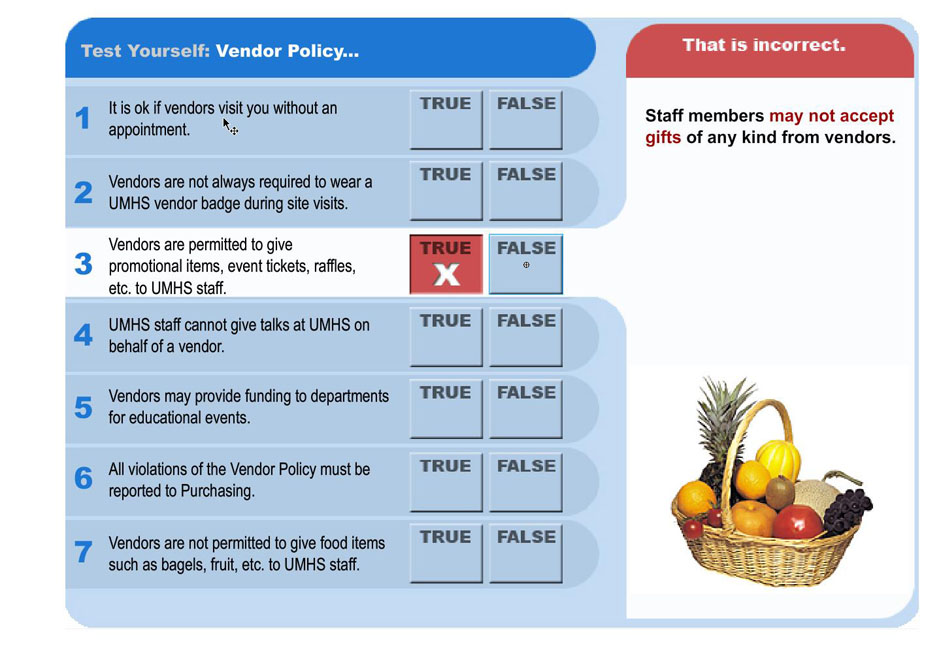

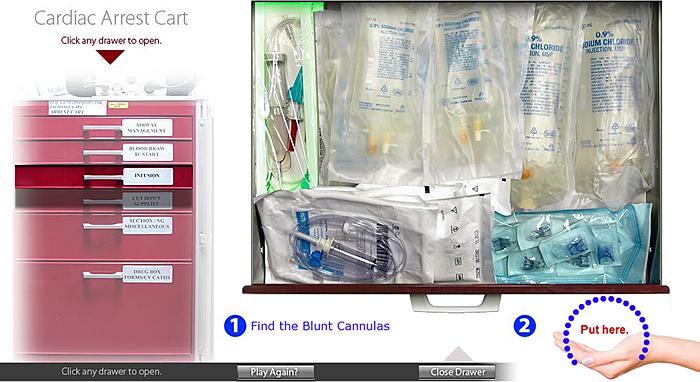

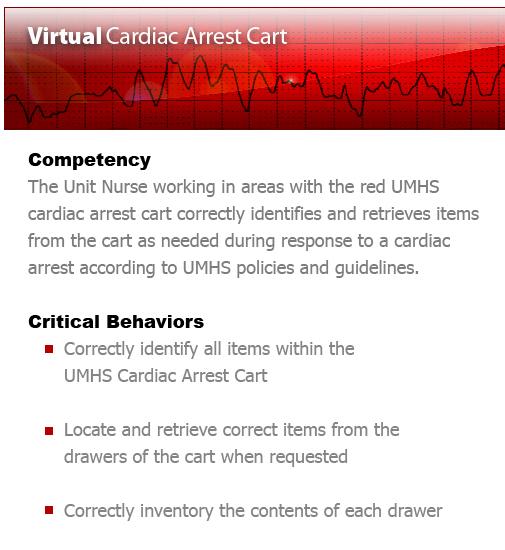

Do you always need to score a quiz? Not necessarily. You might consider inserting a “trial quiz” in an activity to challenge your learner’s knowledge without actually scoring them on their choices. (See Figure 1.) These “mini” quizzes are the perfect opportunity for learners to explore topic examples and to try out their answers without any negative consequence.

Figure

1:This activity provides learners the opportunity to guess and check as they hunt for the correct item in the (virtual) cardiac arrest cart. By intention, the learner is not scored or tracked.

Figure

1:This activity provides learners the opportunity to guess and check as they hunt for the correct item in the (virtual) cardiac arrest cart. By intention, the learner is not scored or tracked.

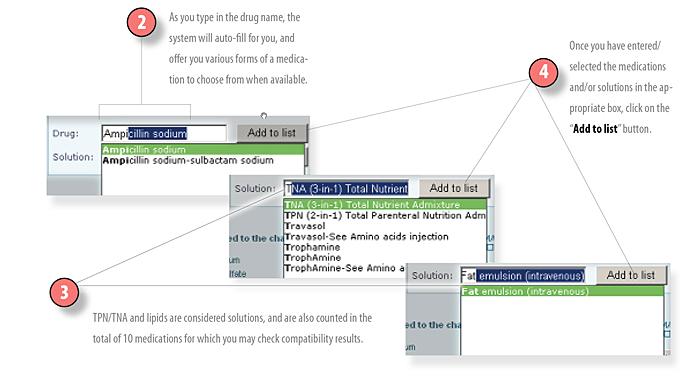

Principle #3: Showing is often better than telling

Many adult learners would prefer to have you SHOW them how to do something rather than have you TELL them how to do it. Even better, many adults would like an opportunity to try it themselves after being shown.

When it takes a lot of writing to define a complex progression of steps, consider using a series of clear images instead. Capitalize on the rich-media technologies that are available in e-Learning. When static images aren’t enough, consider using a short, simple animation or video. Better yet, if possible, provide an interactive simulation of the activity and let your learners practice the steps themselves.

Practical applications

The following three examples illustrate ways to supplement or replace paragraphs of written instructions using images, animation, and video.

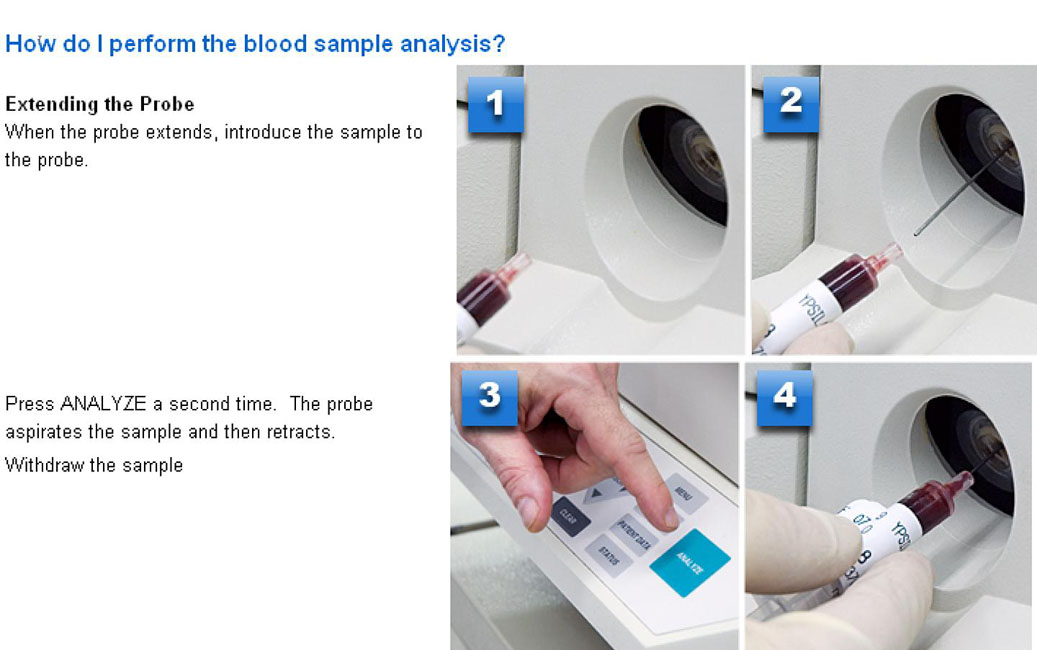

Figure

2: Use clearly sequenced images to demonstrate a series of steps.

Figure

2: Use clearly sequenced images to demonstrate a series of steps.

There is an axiom in medical education that sets an expectation for learners to: “See one. Do one. Teach one.” If leveraged correctly, multimedia options in e-Learning can provide opportunities to repeat and reinforce learning in all three learning domains – cognitive, psychomotor, and affective.

If one picture is worth a thousand words, an animation or video must be worth at least a million!

Animation

Figure 3 uses animation to visually demonstrate the correct protocol for mixing a specimen in a vial. This animation augments several paragraphs of text describing the same protocol.

Figure 3: Use animation to promote learning in the cognitive and psychomotor domains.

Video storytelling: use a video vignette to model behaviors

Figure 4: Three still shots from a video that explains how to deal with an employee having trouble with stress on the job.

Figure 4 comes from a video that illustrates a desired behavior. For behavior change in the affective domain, video-based vignettes can effectively present case studies and “what if?” scenarios to trigger critical thinking skills.

Principle #4: The goals for the learner must be obvious

“Begin with the end in mind”

– Steven Covey

The best way to assure meeting learning and performance expectations is to set them early, concisely, and clearly at the start of the learning activity. A clearly stated course objective or competency statement includes elements which are explicit, measurable, conditional, and unmistakable.

Identify success metrics with your stakeholders and then define them in concrete terms. Stick to them throughout the development of the learning activity.

Articulate the expectations of the learner concisely, plainly, and early.

Example: Identifying success metrics

Figure 5: A clearly stated course objective is explicit, measurable, conditional, and unmistakable.

Well-written critical behaviors should map directly to the course objectives, underscoring the expectations for the learner in very specific terms.

Principle #5: The benefits for the learner must be obvious

Upon encountering a learning activity, the first question your learner will ask is: “What’s in this for ME?” If you don’t answer that question quickly and clearly you’ve started to lose them, and you may not get them back, no matter how well you designed the rest of the activity.

“Marketing is what makes selling unnecessary”

– Peter Drucker

Like it or not, marketing principles apply in e-Learning.

We are competing for limited time and resources. Managers may be reluctant to release staff for education they perceive as irrelevant or of no benefit. Learners will not commit the required level of engagement if they do not invest somehow in the outcome.

Defining Benefits

The benefits you define for a learner should fit within a handful of categories. In many cases the learner who successfully completes your learning activity will benefit through improved competency, renewed licensure, certification, peer recognition, possible advancement and pay increases, and more.

Most adult learners naturally understand the intrinsic benefit of successfully completing a learning activity, but it does not hurt to declare the tangible benefits up front as well.

Learner benefits and relevance are closely linked.

Principle #6: The learning content must be relevant

Adult learners do not want to learn what they will not apply. New skills and information must build upon the learner’s current knowledge and experience. The learning activity must be perceived as meaningful and relevant to the interests and concerns of the learner. When teaching a new skill, what is most relevant to your learners? Is the information in your activity germane to the learner’s experience in your audience? Are you providing opportunities to learn new practices which they can directly apply in their setting?

Don’t expect your learner to dig for relevance in your activity. Shine a light on the relevance in your content and keep your light focused and on point.

Targeting: Is this really for me – or someone else?

When roles vary widely within your audience, consider developing more than one activity on the topic with information tailored to your different audiences.

Is this going to be on the quiz?

Similarly, it is neither fair nor useful to place a question in a quiz on a topic which the learning activity did not cover. Don’t do it. There is no benefit to you or the learner.

How to build relevance

- Get buy-in: Involve members of your target audience in the activity design.

- Collaborate to define the problem and set the goals.

- Ask: “What method(s) do you think will get us there?”

Principle #7: Keep it simple, not simpler.

Albert Einstein once said, “Everything should be made as simple as possible, not simpler.” Long before that, Leonardo Da Vinci noted, “Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication.” Teaching complex topics need not be complicated. The best approach to effectively teaching complex topics is to first holistically examine the desired competency or outcome.

Then, break down the lesson or activity into discrete sections that your learners can cognitively assemble at their own pace. Illustrations, interactivity, and animation are valuable aids for distilling several paragraphs of text down to discernible chunks. (See Figures 6 and 7, and the sidebar for Figure 7.)

Figure

6:You can understand complex steps through clear illustrations and instructions.

Figure

6:You can understand complex steps through clear illustrations and instructions.

Figure 7: In this example, a detailed,

yet uncomplicated illustration,

clarifies a critical step in a standard of care

which was often misunderstood.

Surgical Skin Antisepsis

STEP 4: Using dry, high-level disinfected forceps and new cotton or gauze squares soaked in antiseptic, thoroughly cleanse the skin. Work from the operative site outward for several centimeters. (A circular motion from the center out helps to prevent recontamination of the operative site with local skin bacteria.)

You do not need to make up the cotton or gauze swabs or pads from sterile items. You can use clean, new (not reprocessed) cotton or gauze swabs because they do not contain harmful organisms and will be touching only noncritical (intact skin) and semi-critical (mucous) membranes (Spaulding 1968).

Surgical Skin Antisepsis and SSI Prevention: Technique

Why is proper prepping technique important?

Proper prepping technique is probably the single most important variable to prevent a surgical wound infection.

Clean area vs. Dirty area – it is very important to start at the “cleanest” area of the skin, i.e. the surgical incision site, and move your way outwards with your prep sponge or stick to the “dirtiest” area. You should not track or trace back with your now “contaminated” sponge or stick, because you can transfer the bacteria or yeast around and redeposit it to a “clean” area.

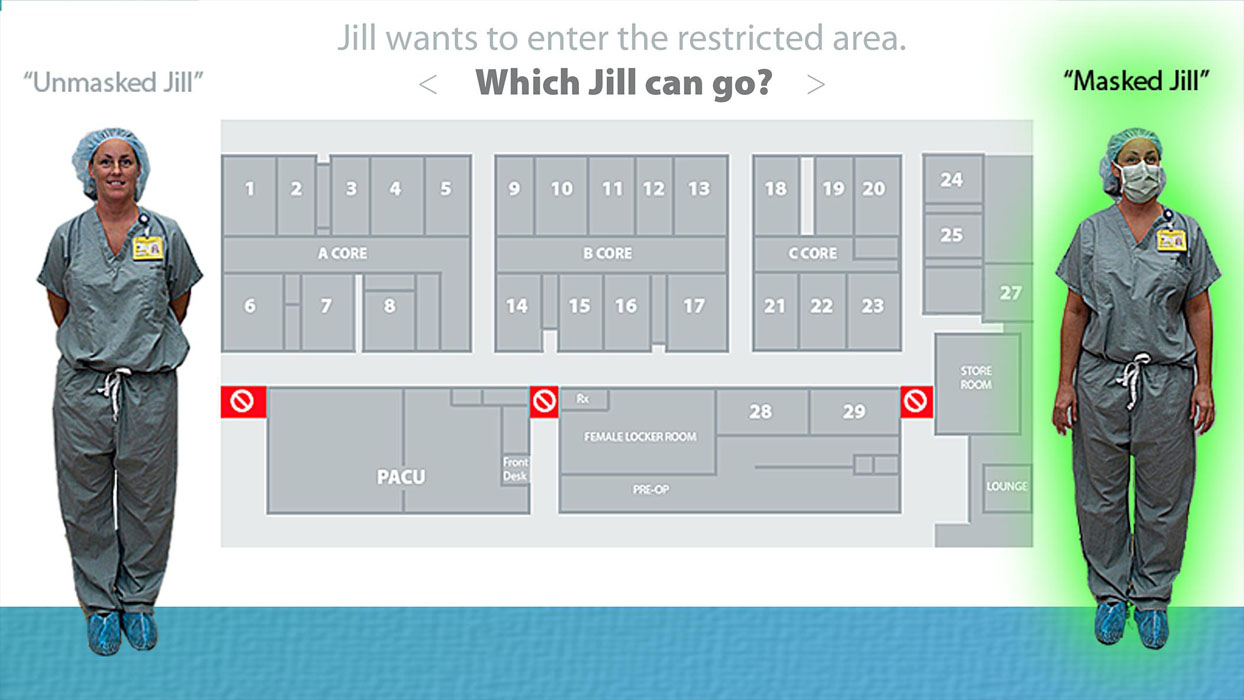

Principle #8: Positive behavior modeling reinforces the desired outcome

Most adults have a propensity to recall most of what they see. In a learning activity, if you solely describe or depict a negative behavior, you will tend to reinforce only that particular behavior. Emphasize the positive behavior and the intended outcome. If it is necessary to portray negative behaviors or outcomes, balance the depiction with the preferred outcome. Be sure to call attention to the desired result. (See Figure 8.)

Figure

8: Balance the depiction of negative and positive behaviors with a

special emphasis on the desired result.

Figure

8: Balance the depiction of negative and positive behaviors with a

special emphasis on the desired result.

Principle #9: One size does not fit all of your learners.

One of the few traits most adults share is that we are self-directed learners with unique histories and varied learning styles. How each of us learns is as distinctive as our DNA. Try to tailor learning for a diversity of learning styles.

It may be challenging to create a single learning activity that resonates with everyone in a diverse audience. For starters, you should acknowledge and accommodate an assortment of learning styles, life experiences, and preferences.

Caveat: Avoid “stereotyping” a learner to a particular style – rather, consider that motivation and current needs will overcome most learning style preference obstacles. Learners have a greater propensity to learn with a number of styles, rather than just a few. Pleasant surprises often occur when you offer more than one style. There are many different learning style theories. Table 1 provides one way to understand learner preferences.

|

A |

Prefers |

Avoids |

D |

Prefers |

Avoids |

|

|

Specific definitions Lots of data Complex problems |

Emotions Undefined concepts Nebulous ideas |

|

Imagery Flexibility Metaphors |

Regimentation Structure Excessive detail |

|

B |

Prefers |

Avoids |

C |

Prefers |

Avoids |

|

|

Trial & error Structure Precise instructions |

Risk Ambiguity Vague ideas |

|

Group work Physical activities Personal sharing |

Over analysis Solitude Autonomy |

|

Source: “Whole Brain Learning Design Strategies” Herrmann International - USA |

|||||

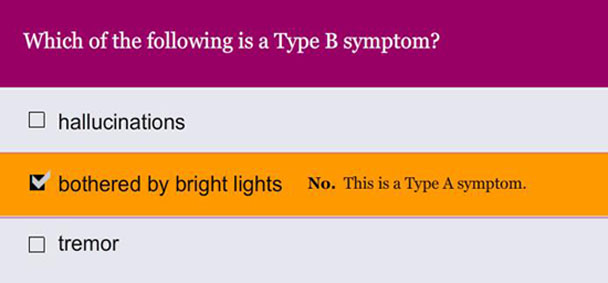

Principle #10: Quiz/answer feedback should be immediate and corrective

With Web-based learning, adults have come to expect to learn if their quiz answers are correct – and they want to know right away. And, if their answers are incorrect, they want to know why. Astute learners in a teaching health care setting are especially prone to questioning the content expert of a lesson. When learners receive immediate, authoritative feedback on their participation and progress within a learning activity it fosters adult learning.

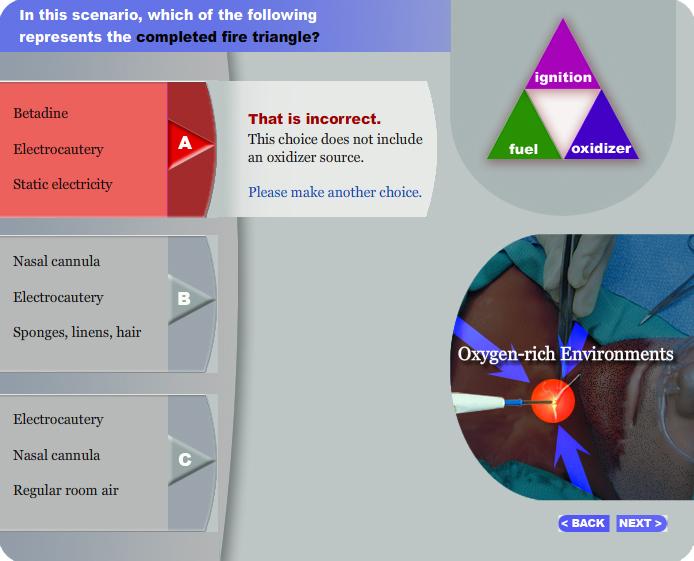

It is now very easy to provide immediate and corrective quiz answer feedback. This is true whether the learner’s answer is correct or not. In fact, incorrect responses in e-Learning are excellent opportunities to improve critical thinking by way of guided, informative feedback. (See Figures 9 through 11.)

Caveat: be mindful of the difference between “spoon feeding” a correct answer and providing corrective feedback. Fostering critical thinking is the goal.

I also recommend including an e-mail link within a Web-based lesson to provide an important channel of communication between the learner and the educator.

Figure 11

Figures 9, 10, and 11: Quizzes with immediate feedback.

Principle #11: Understand what motivates your learners and what gets in their way

“Teachers open the door. You enter by yourself.”

- Chinese proverb

What prompts a learner to enter that door? What motivates your learners to successfully complete an activity? What gets in their way? Designing for learning is often a delicate balancing act. You must know what will inspire scholarship and what might immobilize or inhibit inquiry. (See Table 2.) In other words, you must light the path and steer them to the door.

For example, if you know that your learners are going through a particularly busy or stressful period, consider delaying your educational requirement until another time. On the other hand, if you know that your learners are eager to advance or improve a competency, or adapt to a changing situation, create opportunities for them to achieve those goals.

Light the path and steer them to the door.

MOTIVATIONS: |

|

OBSTACLES |

|

|

The following is a partial list of motivators which drive a learner to successfully complete a learning activity. |

The following is a partial list of obstacles which may inhibit or immobilize a learner from successfully completing a learning activity. |

||

|

Lack of time: conflicting demands, multiple responsibilities Confidence: pressure to prove competence, meet a requirement, maintain licensing, learn new skill Lack of interest: lack of information indicating relevance to learner-pressure or fear of failure |

||

Principle #12: Peer reviews and pilot testing will keep you from getting stung

If you send out your learning activity without putting your content through a rigorous peer review and a pilot test (see Table 3), you are inviting problems that you might not have expected. If something is wrong, or simply too confusing, your learners will swarm and let you know!

Conduct two peer reviews

Creating learning materials can take some time, and involve a number of people. Even the best educator can make a mistake. To avoid getting stung by unexpected problems, you should put your learning content through a careful peer review with another expert at least twice during the process – once in the beginning and once near the end of developing the activity.

Pilot test

Following the final peer review, allow time to conduct a small handful of pilot tests. To conduct a pilot test, recruit three to four members from your target audience. Ask these learners to step through the entire learning activity. Ask them whether the information and the sequence of the learning content made sense to them. Check their quiz scores to verify.

Allow some time after the pilot test period to make any necessary adjustments to the learning activity before rolling it out to your entire audience.

You’ll be glad you did this. Managing your e-mail will be much less painful, too!

Peer Review: |

|

Pilot Test |

|

|

Review once in the beginning, and once near the end of developing the activity. |

Check for problem areas. |

||

|

Why

do it? |

Why

do it? |

||

|

Who’s

included?

|

Who’s

included?

|

||

Conclusions

Long-established adult learning principles are still highly relevant in e-Learning.

When you omit or ignore one or more of these principles, it affects learning outcomes negatively.

Successful course development hinges upon the appropriate application of these time-honored principles.

Parting gifts

How to succeed as an educator, SME, CLO, Instructional Designer

- Be curious: Listen to your stakeholders but also be curious about your learners in order to interpret effectively.

- Focus on outcomes: Be both a learner advocate and a stakeholder advocate. Learner success is stakeholder success.

- Facilitate learning: Make it compelling - not cumbersome. Learner motivation is the biggest challenge we face (and it’s often out of our control).

References

Dewey, John; Boydston, Jo Ann; Hook, Sandy. The Later Works, 1925-1953. Volume 17: 1885-1953, pp 269-284.