The San Francisco Bay Area chapter of the Chinese Institute of Engineers/USA held its annual conference on February 27, 2016 at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California, with a meeting focused on innovation and the maker movement. In the afternoon session, seven speakers provided multifaceted perspectives on the theme “We Are Makers.” The evening banquet featured a keynote titled “My Encounter with Innovation” from Dr. Chenming Hu, professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Hu is also a recipient of the National Medal of Technology and Innovation, presented to him in December by President Barack Obama.

Figure 1: Dale Dougherty, founder and CEO of Maker Media, received a plaque for his contribution to the CIE conference

Dale Dougherty, founder and CEO of Maker Media, kicked off the conference with a keynote about how the maker movement is shaping the next generation of engineers, designers, and innovators. Dougherty attributed the rapid expansion of the maker movement to the experimental, expressive, and sharable experience of the maker mindset.

Dougherty explained, “Making is simply starting with some idea in your head and beginning to work it out, bringing it out of your head, and making it through some sort of process through tools and materials. It is our own process, and it’s really satisfying to take something that you weren’t sure about and to begin acting on it. Making is something that we all do, not just a few, or just at work, but something we can do in our garage and community.”

Dougherty’s speech emphasized how the iterative and creative process of making fosters many attributes in children, and even adults, that aren’t always readily accessible through the current learning curriculum. He says, “You get better at doing it repeatedly; you have different abilities to continue to make. In schools, we can’t have enough time to practice and improve—we learn in such small doses in schools that we don’t have the ability to practice and improve.”

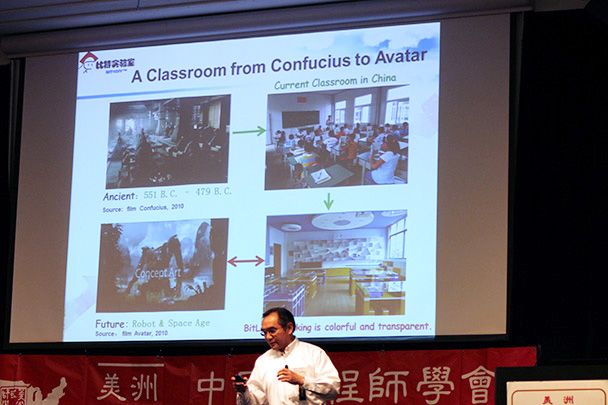

Dr. Weixun Cao, founder and CEO of BitLab, recognized the importance of sharing the maker mindset and process with students. Dr. Cao presented his experience in establishing more than 200 makerspace classrooms in over 20 provinces in China. Educational approaches in China differ vastly from approaches in the United States—where the maker movement starts bottom-up within communities in America, it is the reverse in China. Educational approaches and mandates come top-down from the Chinese government.

Dr. Cao explained that Chinese educational culture revolves around obtaining the best examination scores to get into university, a process that is inherently focused on the individual. In 2010, China passed the Outline of National Plan for Medium and Long-range Education Reform and Development (2010 – 2020) in order to shift from caring about the “cold score” to the “living person.” This reform, along with Chinese Prime Minister Keqiang Li’s statement that everyone should be an entrepreneur and innovator, has sparked national interest in the maker movement.

Dr. Cao took this new national interest as an opportunity to implement his vision for BitLab. His purpose is to get students focusing on creating a product using the three Ps—passion, product, and projects. He’s cultivating the youth mindset to utilize innovation, creativity, and teamwork by developing products that could better help society and bring us into the future. These colorful spaces (Figures 2, 3, and 4) are designed to foster effective problem-solving skills under the traditional learning environment of a classroom. Dr. Cao worked with policymakers in China to approve and create classrooms that were fully DIY (do-it-yourself)—from the chairs and furnishings to the décor. Tables and chairs come in kits that students are able to assemble. They are modular, easily pushed together to encourage teamwork. Table surfaces are transparent, allowing students to follow along with a textbook or their tablet computer underneath the surface while they create and experiment with projects on top of the desks.

Figure 2: A BitLab makerspace in China

Figure 3: BitLab makerspaces are colorful

Figure 4: BitLab classrooms with modular tables and chairs

Curricula of the BitLabs include four main components: learning the history of inventors and scientific discoveries, building electronic sensor–based systems, assembling 3-D prototypes, and presenting and public speaking. Students utilize a variety of sensors (including light, sound, ultrasonic, and motion sensors) in geometrically shaped housings, as shown in Figures 5 and 6, to create products that can have a variety of applications ranging from smoke alarms to pedometers. The end product is up to the students’ imagination.

Figure 5: Sensors that students use to create products

Figure 6: Geometric shapes used to house the sensors and create prototypes

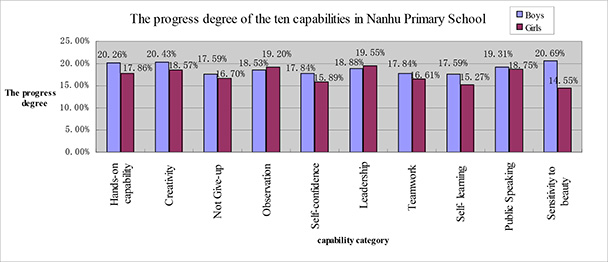

Each session is 45 minutes on a weekly basis, but results have been positive in increasing students’ creativity, observation, and confidence, among many other qualities. At the beginning of each class, students fill out a self-evaluation of 10 abilities, and after the completion of the semester, they fill out the same evaluation. Dr. Cao noted that the students’ progress was not limited by their traditional gender scopes; for example, the improvement of boys in their sensitivity to beauty was much higher than the girls’ improvement, and the girls’ progress in leadership was higher than the boys’ (Figures 7 and 8).

Figure 7: The progress degree of the 10 capabilities in Nanhu Primary School

Figure 8: Dr. Weixun Cao explained the evolution of traditional classrooms to makerspace classrooms

Dr. Cao’s BitLabs illustrate the power of the maker mindset to break barriers across continents. His classrooms demonstrated Dougherty’s vision, as the Maker Media founder described in his opening speech: “The incredible thing about the maker movement is that it connects all forms of interest people have. Part of what I wanted to do is to bring people together and introduce them to the practice of making again in an ordinary way.”

As the evening wrapped up, Dr. Hu presented a keynote describing what innovation meant to him. The UC Berkeley professor emeritus summed up innovation as “solving problems that matter.” Dr. Hu explained that we often need to re-examine the original problem and to look at it from different perspectives to get to the right answers, as the best answers are not the ones that we arrive at first. His focus on the iterative process toward innovation and problem-solving was echoed by Dougherty’s viewpoint on making: “It is a practice. It’s not something you do once and you complete. You get better at doing it repeatedly; you have different abilities to continue to make.”

The Chinese Institute of Engineers/USA will celebrate its 100th anniversary in 2017.