Last month I wrote about the duration of people’s attention span, and this month I want to take on a related, equally important question that I hear a lot. It is phrased something like this: “My learners often don’t understand my training. Should I start writing at an eighth-grade level?”

What is going on here? Are our employees such poor readers that they can’t understand our simple sentences?

In fact, research does show that reading has declined a little among Americans. But for the most part, the decline is small, and I do not think that the employee’s poor comprehension is the result of their reading skills. Instead, I think the communication breakdown has to do with the fact that we, as teachers, are writing in ways that do not conform to the way the human brain expects to receive ideas.

We will explore this idea over the coming months, and I’d like to begin by exploring exactly what we mean by the idea of “writing at a grade level.”

What is the “grade level” of writing?

You have probably heard the newscasts claiming that the average American reads at the ninth-grade level. What does this mean?

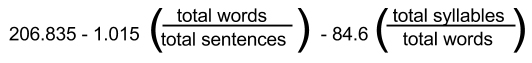

The “grade level” of a piece of prose is determined by calculating two factors: the length of the average sentence and the sophistication of the vocabulary. In short, we assume that bigger words and longer sentences make sentences harder to comprehend. For example, the US Navy developed the well-known “Flesch-Kincaid” test in 1975. Their equation is as follows:

According to the developers, if a passage scores about 100 (i.e., its sentences have just a few words and those words have few syllables) an 11-year-old can easily understand it. If the passage has a score of 60 a 14-year-old can understand it, and if it has a score of 30 university students can understand it. You can check this out for yourself using this online readability tester.

This equation looks very sophisticated, and as a result, it creates the illusion that an equation can define meaning. In fact, however, very short sentences with simple words can have little meaning. Consider Noam Chomsky’s famous statement:

Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.

This sentence has only five words, each word is familiar, and the sentence is grammatically correct. However, this simple sentence has no detectable meaning for anyone.

In contrast, almost anyone can understand some long sentences with complex words:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

How long should my sentences be?

Keep in mind that a sentence is a unit of expression that expresses a single idea, so your sentences should be exactly the length you need to communicate your ideas to your reader. In general, short sentences are easy to write, they are easy to read, but they can usually communicate only simple ideas: “See Jane Run.” If your training concepts are straightforward, you can probably get away with sentences averaging 8 to 12 words.

In general, longer sentences are harder to write and they are harder to read, but as sentences grow longer they are capable of communicating more sophisticated ideas and more nuanced meaning. The problem is that when sentences get longer, most writers have difficulty managing the grammatical structures and hence their reader is likely to get confused. If your training concepts are complex, you should probably provide sentences that average 20 to 25 words.

Vocabulary

The second component of complex language has to do with vocabulary. Let’s do a simple experiment:

As you know, some trainers use fancy language just to impress the learner with their knowhow. This is silly. When you use unfamiliar words, it slows the reader, and it obscures your meaning.

Now let’s compare those sentences with the following:

As you know, some trainers use sesquipedalians just to impress the learner with their knowhow. This is silly. When you use sesquipedalians, it slows the reader, and it obscures your meaning.

Which passage does a better job communicating ideas?

For most people the second passage is much less clear because the term sesquipedalian is unfamiliar. In fact, the word sesquipedalian just means “big word” (“sesqui” means “one-and-a-half,” and the root “ped” refers to “feet;” hence, sesqui-ped-alian refers to words that are one-and-a-half feet long). Most people find that the first passage, with its clear and understandable terms, much easier to comprehend.

This does not mean that you should only use simple words. My writing mentor, Dr. George Gopen at Duke University, advised me that I should always use the simplest possible “perfect word.” If I am choosing between words which essentially have the same meaning, for example “use” and “utilize,” always pick the simpler one because it will make the point without placing any extra cognitive burden on the reader.

However, there are times when you must select a less familiar term because it conveys exactly the meaning you want. This is especially true with compliance training or when you need to make a company policy crystal clear.

Choosing the perfect word is a challenge that forces you to choose between a common word that is close to your intended meaning and a more obscure word that has exactly the right meaning. This choice is part of the fine art of writing and you will need to decide whether the benefit of familiarity is more important that having the exactly correct word.

Should I worry about the grade level of writing?

Some trainers complain that Americans are poor readers and that we need to be “writing down” in order to reach them. In contrast, my take-home message is that you do not need to worry about levels of writing. “Levels” are just a silly shorthand that says nothing about meaning or efficacy. Instead, you need to worry about clarity of your expression and whether you are delivering lessons in a form that is compatible with the learner’s brain.

Is there a justification for writing long sentences and using an advanced vocabulary in training? In my opinion, the answer is ... sometimes. In some conditions, our training task is straightforward and simple short sentences are sufficient. At other times, however, our ideas are complex and we need longer sentences and less familiar terms to make ourselves perfectly clear.

In the coming months, we will look at how your brain processes the written word and provide you with a series of tricks and techniques that will help you speak coherently and in a language that the brain understands.

Digging deeper

If you want to write more effectively, George Gopen’s The Sense of Structure: Writing from the Reader’s Perspective and Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style are two indispensable places to start. And if you have favorite guides to writing, I encourage you to share them in the comments section.

If you would like to have your memory of this article boosted, send an email to ELGboosterJuly2014@AKLearning.com. You will automatically receive a series of boosters on this three-article series. The boosters take only seconds to complete, and they will profoundly increase your ability to recall the content of these article.