If clients have ever asked you or your teams to create or re-design an e-Learning solution, chances are you’ve had conversations with those clients about success and quality. You know the ones. The conversations where you attempt to understand what exactly your clients mean when they say: “We want a Lexus; something with a big wow-factor that doesn’t necessarily have to have all the bells and whistles.” Or: “We just want something simple — something that will get the point across.” Or: “We want our PowerPoint deck spruced up a bit so that users will become more aware of XYZ.”

If you’re like me, you’ve emptied plenty of Tylenol bottles over the years dealing with the headaches of trying to successfully navigate the consulting challenges within this potentially “highly-ambiguous-no-real-insight-in-sight” conversation.

Could This Be You? (Episode 1)

Let’s consider the conversation within a slightly larger lens. Here’s a clip of a typical discussion I’ve seen played out many, many times. (Names have been changed, but these are the actual words.) The scene: Tom, a designer, has 10 minutes with Sheila, a very busy executive, in order to understand her expectations for a new e-Learning solution she wants Tom to create for the employees working within her division. Tom, a veteran, knows the challenges of this meeting. He only has those few minutes to get her view of the success and quality levels she’d like the solution to meet. We enter the scene just as he begins asking his key questions…

Tom: From your view, what does success look like for this solution?

Sheila: We want everyone to complete this course and learn all there is to know about X. It’s tremendously important to our business. People really need to know the details of how X works and how it drives our business. The more they know, the more it will help all of us.

Tom: Great. Describe the kind of impact you see this having on our organization.

Sheila: We want this to be revolutionary. We want it to create a ton of excitement and buzz about X so that people will join the bandwagon.

Tom: What do you mean by revolutionary?

Sheila: Something engaging, experiential, entertaining, and fun — never before seen in this organization. We want it to motivate employees to do X every day.

Tom: Say more about this. What’s your blue-sky vision of how you see the learner learning?

Sheila: Oh, I don’t know — something that allows them to practice X in a situation. You know who you could talk to about this? Joan and Akrim over in XYZ division. They’re closer to this than I am. And it might be useful to speak to some of their reports as well, you know, people who will actually take this training.

Tom: Ok, I’ll follow-up with them. I think I have everything I need at this point. Thanks for your time.

How did Tom do? Did he clarify the ambiguity so he can quickly convert his client’s conceptual thoughts into a learning design strategy that this executive can support and evangelize within her own division? What does engaging really mean for the design and the impact this executive desires? Now that the meeting is over, how does Tom meet the executive’s “design” expectations AND the extremely tight timeline and low-cost expectations?

In simple terms Tom’s consulting success path looks like this: how does Tom meet the fuzzy proverbial “bar” this executive has described? How can Tom “unfuzz” the bar now, and should he? How does Tom meet seemingly lofty design expectations AND time and cost expectations? And finally, if Tom guided the conversation in a way that helped the executive quickly clarify the bar in the first place, how would it matter?

I’ve found it matters greatly.

When the designer can clearly guide and define the success and quality conversation with clients upfront when determining the solution, it's possible to reduce the time needed to scope the project by 20-30%. It’s also possible to cut the time needed to ideate a learning strategy and design plan by as much as 20%.

When done effectively, this conversation sets the learning design on a steeper success trajectory for learner acceptance and performance impact, for stakeholder support, and for positive, trust-filled client-designer relationships. In this business environment, where the desire is for the highest learning impact for the lowest cost in the shortest amount of time, the two key skills for anyone who creates learning solutions are to quickly clarify and calibrate ambiguities about success and learning strategy direction.

The following is an overview of consulting strategies and techniques that learning designers can use to clarify and calibrate. These are proven strategies and techniques that increase the impact of e-Learning solutions. They help learning strategists and designers quickly and flexibly manage and meet fast-paced, ever-growing stakeholder and client expectations. Although these strategies can be used throughout a design and development cycle, they are best used early on, at the point of solution determination.

Strategy #1: Calibrate your success perceptions

You’re working with a client to create a new e-Learning solution. Before you discuss the solution, consider asking yourself this question: where are you both coming from? Think about it. People from different backgrounds, disciplines, and varying experience levels come together to create a “thing.” Varying perceptions based on pre-conceived ideas and experiences are a reality. Taking time to unveil hidden (or not so hidden) perceptions and biases, in order to make adjustments possible, can help relationships thrive faster and can help the creative process progress quickly. The strategy, admittedly, is based upon a simple premise. If you know your attitudes, and how far you have to adjust them, you will. Conversely, if you know where your client’s attitudes are, and where you’d like them to be, you will be in a better position to work with them to help them move there. Ultimately, this strategy sharpens understanding and outcomes of any success conversation.

How to implement this strategy

Here are two approaches.

- Approach A: List common perceptions your client(s) have in terms of success and compare your perceptions to see how you both align.

- Approach B: List consistently occurring perceptions across many clients and compare your perceptions.

You can do these openly with the client or privately on the side. The key is to keep it simple and targeted to perceptions you see as potential roadblocks. As you engage your client, take note of which comments make you tense, pause or instinctively wonder. Trust your experience and intuition and create a list based on those.

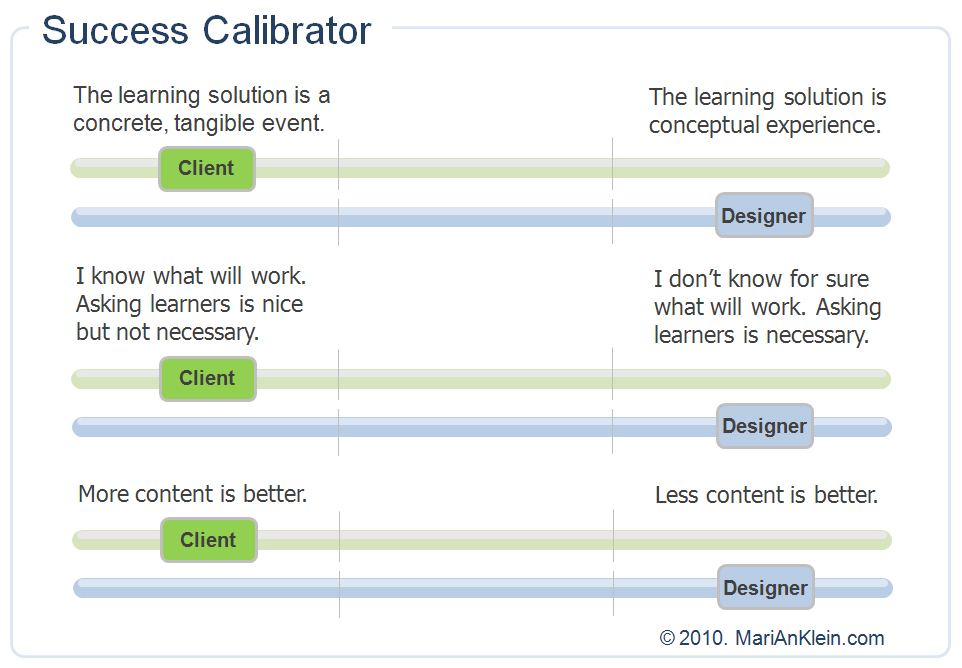

Here is an example of a calibrator I use (see Figure 1). I’ve listed consistently occurring perceptions and attitudes I’ve found many clients and designers tend to exhibit related to creating learning solutions, solving problems, and content design. The figure shows how things may look like after a client and designer first meet. Your calibrator, of course, may look different depending upon your list and perceptions. Nevertheless, upon first meeting a client, I use this list and mark on the continuum where I think the client falls, based on reactions I’m hearing in early meetings in which we are working out solutions. I then mark where I fall on the continuum and compare.

Figure 1: The generic success calibrator

Replaying Tom’s Strategy Play

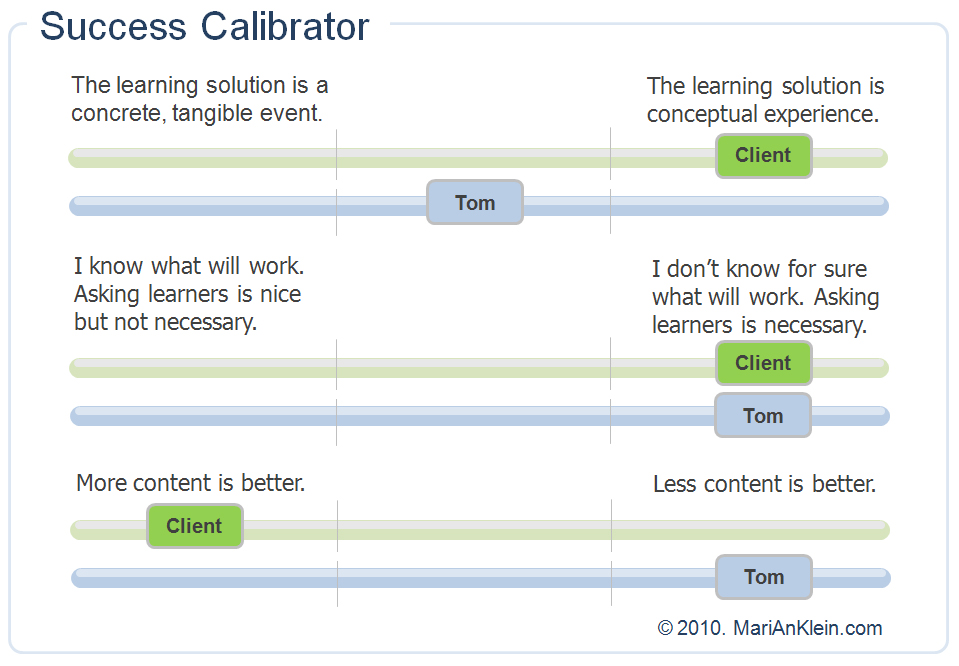

Let’s return to Tom’s conversation. Figure 2 is representation of what Tom learned from his client. It’s a quick consulting roadmap Tom can use to quickly anticipate issues and begin to influence effective design direction.

Figure 2: Tom’s calibrator after the first meeting with Sheila

Tom and his client, Sheila, nearly agree about the solution being some type of experience (this information will drive the type and complexity of design methodologies they will eventually choose, such as scenarios, simulations, or games). They agree that asking learners is important. Tom can now feel confident about including learner focus groups or formative testing in his approach. Finally, Sheila strongly believes that including detailed content (code word for “more content is better”) is highly important. Tom and Sheila are far apart on this. So, how can Tom begin to “unfuzz” the bar and clarify expectations?

Replay

Sheila: We want everyone to complete this course and learn all there is to know about X. It’s tremendously important to our business. People really need to know the details of how X works and how it drives our business. The more they know, the more it will help all of us.

Tom: [insert rewind sound] Great. Describe the kind of impact you see this having on our organization. Say more about this. Do you want to see much of the content found in the 200-page policy document in this solution?

Sheila: Well, yes. That document was created by the steering committee. A lot of people played a part in getting that done and approved.

Tom: I know that getting this training rolled out quickly is highest priority for you, but an aggressive timeline and a non-prioritized content strategy work completely against each other. Prioritizing content and presenting in an engaging simple manner, particularly given the importance of this topic and complexity, is critical for getting this completed effectively and on time. We’re committed to making this a success for everyone. Your help in communicating this across the project team will save us a ton of time. Does this make sense and can you help us?

Note how Tom capitalized on knowing/seeing the disparity of views and began to solicit buy-in to a high-level design approach immediately. When compared side by side, the success trajectories of the design for each of these solutions will likely be very different.

You’ll find your success-calibration list will likely come out of asking questions such as, “In your view what does success look like? What’s your blue-sky how-will-it-work vision for this solution?” The opposite (and less successful) approach is to ask your client where they think they land on these continua. I’ve learned not to ask clients these questions in a rapid-fire or question/answer approach. It gives the conversation a disjointed, clinical feel, as if you’re giving your client a psychological test. In the end, seeking the answers to your client's expectations within the context of a conversation and open dialogue results in better understanding and relationship.

As you know, not everyone’s views are black or white. That’s why I’ve found a continuum works best to quickly identify how far your perceptions are apart from your client’s. The success calibration strategy has four values:

- It eases potential consulting tensions and helps people connect. Relationship connection is a key factor in making great design.

- It reduces rework and frustration arising from misperceptions, and it increases design success.

- It reduces time spent determining a solution.

- It helps make leading and managing easier because consulting issues are made clear.

Let’s look at another example.

Strategy #1 in play: “Could This Be You? Episode 2”

The scene: Jennifer, an e-Learning Manager, has just received a tense call from Omar, a developer. Omar is frustrated: his client is not accepting his ideas.

Jennifer: Omar, I hear your frustration. Tell me about the situation.

Omar: I’ve reworked X three times. I don’t understand why they’re not accepting my ideas. I’m wasting time. We’re reworking what we’ve reworked. Ugh!

Jennifer: It must be very frustrating. What could you do differently to stop the rework?

Omar: I’ve tried everything! I don’t really know.

Pause. Let’s rewrite

this scene. Imagine Omar was asked to use the success calibrator weeks earlier.

Jennifer: It must be very frustrating. What have you done to align your success perceptions with your clients? Where were you and your client weeks ago and where are you and your client now?

Omar: I’m still here and they are still there. [He said, looking at the Success Calibrator] Oh. My consulting tactics really aren’t working. I see the problem. We’re not aligning. I could be doing more of X and less of Y to get closer alignment.

Strategy #2: Define “it” by its purpose then gain buy-in using sound bites

So, they've asked you to create an e-Learning management training course. Your client uses the term “course,” his reporting managers use the term “course” … everyone calls it a “course.” It doesn’t take long before everyone on the project team believes the solution that will work best is a course. Everybody places the design in a mental box, and expectations dictate that everyone should play “inside the box.” How can effective, useful design, let alone innovative design come out of this political whiplash of “solutioning?” First, it’s important to proactively influence clients, particularly leaders, when they approach your learning division, department, team, or you, with a solution born solely out of anecdotal information and perceptions. Here are some questions that have worked for me: "Are you open to considering other options to solve X, rather than a course?" "It sounds like you feel certain a course will solve Y issue. Why?"

If you’ve been successful in influencing leadership to play outside of the box and have won the opportunity to shed light on other options that might be more effective, consider it a big win but avoid thinking the race is over. As you know, the ideas for what it can be lie within the analysis work that you do with learners and stakeholders. Your success path has two parts. First, outline the effective, high-impact option(s), and second, communicate the options to leadership. This strategy focuses upon the second part.

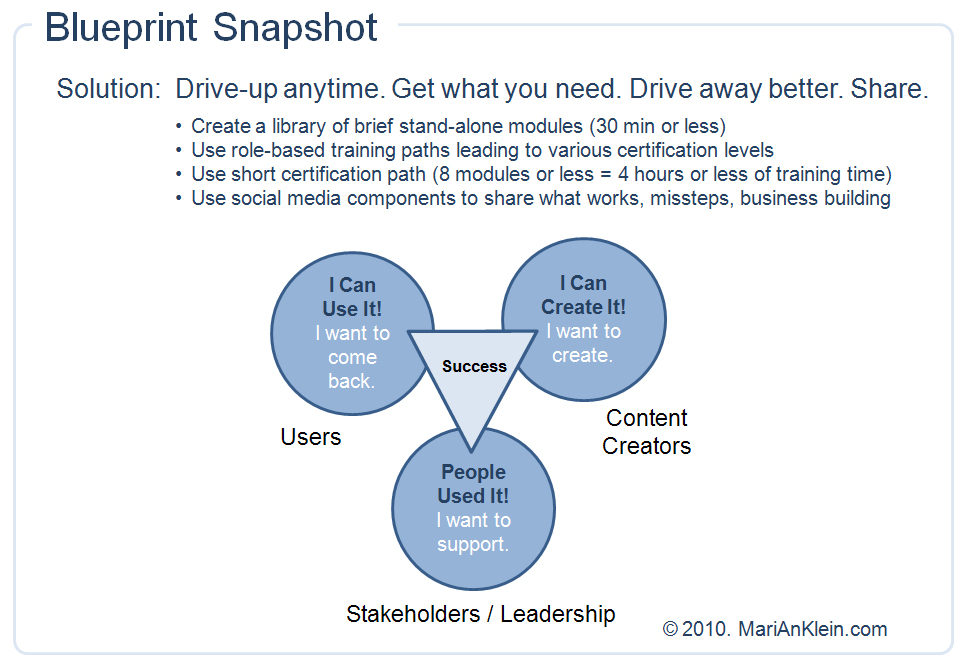

I’ve witnessed many highly effective, even extremely innovative designs passed up because of ineffective presentation and communication. It’s critical to present the solution (“it”) in a memorable, simple, easy-to-consider way. Because great design grows out of purpose, nothing works better than to convey “it” in terms of its purpose. Simply ask: What’s the purpose of it? (This is a question about the type of targeted impact or reaction, not about the learning purpose.) What can it do for the learner? Or what should it do for the learner to motivate them to learn or do the thing you want them to know or do after they complete “it”? Good example of “it”: It’s a highly interactive course that uses brief scenarios and role-play to help the learner practice. Great example of “it”: It’s an interactive commercial-like sitcom that gets people to think and react on the fly. Do you see how setting the purpose can adjust or reset your success trajectory ever so slightly along the good-to-great continuum? Design strategy, methodology, features … all can rapidly emerge when the purpose is defined. It’s especially successful if you describe “it” using a metaphor or analogy of a known tool or concept. Examples: “It’s like a drive-thru. Drive up. Order up what you need. Drive away better." Using this context breaks constraints that might influence presenting the learning in a module, page-turner, e-Book-like approach.

How to implement this strategy

Approach the meeting where you’ll unveil your options as if it were a commercial. Share the design in ultra-concise materials that heavily feature visuals, supported by sound bites. Rather than calling the material a design plan or training plan, call it a blueprint and leverage the value of the blueprint metaphor for all it’s worth. Remember, you’re not presenting a presentation or plan. You are conveying a commercial. Using PowerPoint as the presentation tool tends to work well. It’s a familiar medium to everyone. Figure 3 is an example: a blueprint slide conveying high-level solution components to project team members in a kick-off meeting. Note that it doesn’t share actual solution details.

Figure 3: A blueprint slide gives project team members the high-level components

The challenge with this approach is to avoid spending tremendous amounts of time creating materials for this meeting. Keep the presentation down to less than 5 slides, and leverage it as a visual or working prototype. Additionally, recording the meeting makes the presentation reusable content that leaders can share with others quickly. Moreover, as additional or new project team members join the project, it becomes a commercial for the design and direction in the truest sense of the word.

Ultimately, this strategy has three values:

- It increases the likelihood that they will embrace the solution.

- It underscores the ability of the designer (or design team) to distill the complex in memorable messages.

- It saves significant time in production because messages are succinct and easily understood.

Strategy #2 in play: “Could This Be You? Episode 3”

The scene: Karen, an executive sponsor of what is desired to be a flagship e-Learning sales management training program, has asked the e-Learning Team to produce it as quickly as possible. Tom, a Learning Strategist was assigned to work with Karen, her reports and three other divisions to design a pioneering online experience. Everyone knows that out-of-the-box thinking is required, so Tom’s job is slightly easier. Now he just has to pitch his solution in a way that captures attention and buy-in. We enter the scene, just as Tom begins presenting the proposed design strategy.

Tom: The design team took many hours to consider a solution that would meet all the needs that we’ve discussed. We’re excited about this solution and feel it’s the best option. Let’s turn to the document that the team sent to you. We’d like to review the features and details of it for the next 30 minutes, and then take the remaining time to answer any questions you might have. Although it’s 20 pages, we plan to just highlight the key elements of the option. Let’s begin with the bullets listed under learning strategy. [10 minutes later] Let’s now go to the next section titled Learning Path. I’ll skim over the main bullets here.

Pause. Let’s rewrite this scene. Imagine Tom approaching the presentation as if it were a commercial, and using sound bites to underscore strategy.

| Tom Says: | Slide Content: [just words; no visuals unless stated] |

| What will it take to make this solution a flagship experience? Experiences. | Experiences. |

| Engaging, real-world experiences that place the learner in a virtual office designed to mimic a true-to-life management experience. This is really about changing attitudes through experiences. Experiences that not only explain the “what” but also conveys the “why’s” and the key “what’s in this for me” key messages. | Change Experiences. |

| We want the learners to drive up, practice, and explore, then drive away better. | Drive up. Practice and explore. Drive away better. |

| The learning path is definitive and simple utilizing four mediums heavily leveraging social media. | [Four boxes with simple labels: Virtual Classroom, Coaching Tool, Manager Coaching, Online Discussion Boards] |

| Let me show you how this would work. [Tom describes a day-in-the-life of a manager using this solution.] | A day in the work-life of Susan. A work-life changed. |

Strategy #3: Clarify and calibrate success in terms of the learner

Qualifying the quality of learning solutions is highly integral to any production team or department, not to mention clients. Clients want and need to know what you will create and what the included features are that will specifically help learners learn and perform. It’s a fair expectation. One that always leads down the road to: “How much will it cost and why?” and “How well will this solution meet our business goal?” In a tight-budget, results-focused environment, these questions are magnified. When cost, time, and quality go head-to-head, it seems that quality is always given the short end of the stick. I believe it is because quality is not clearly defined in terms clients can directly equate with their business goals. Defining quality in terms of impact to the learner is essential.

Nothing lengthens the scoping and creative process, and ultimately production, more than determining a solution that is not tethered to an impact goal. The premise: If you can focus the conversation on criteria that are directly related to learner retention, reaction (not likeability), and targeted behavior, then the solution identification phase can be significantly streamlined. Leadership will have tangible, measurable criteria that make sense out of highly conceptual conversations. Design elements can be quickly determined and aligned to meet chosen targets. Focused conversation enables everyone to speak about success using the same terms. Moreover, such focus quickly enables everyone to check progress and outputs against simple agreements throughout the project cycle.

How to implement this strategy

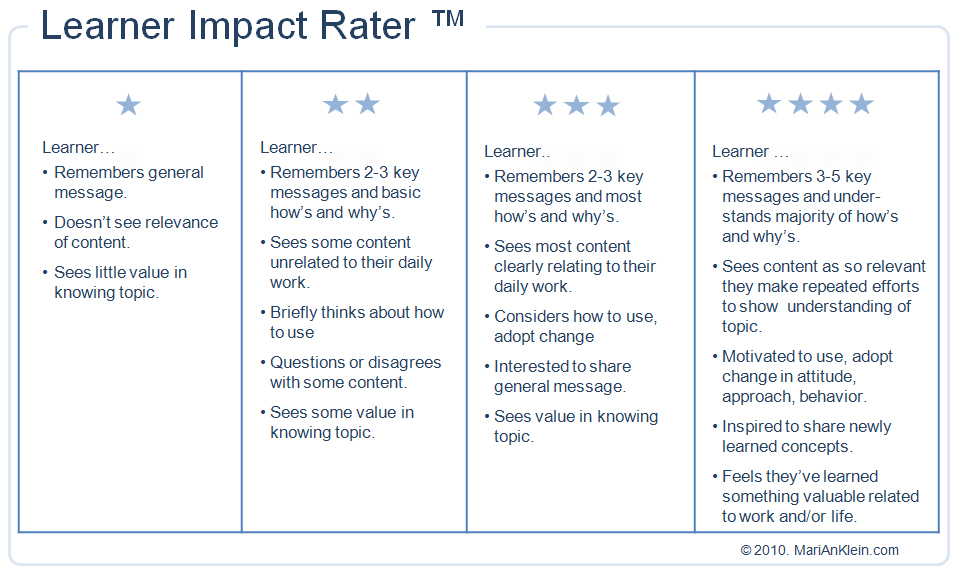

Use the Learner Impact Rater™ in scoping meetings or meetings determining success or solution. Simply ask: “What level of impact would you like to see this solution meet?” (See Figure 4.)

Figure 4: The Learner Impact Rater™

The Learner Impact Rater works for any type of solution. It solidly sets the design conversation upon a results-focused foundation. It eliminates the dizzying feature-focused conversations that so often stall solution identification, or worse, that result in misdirected, misguided, or mediocre outcomes. This strategy and tool has three critical values:

- It saves significant time in solution identification because criteria are tangible, structured, and easily understood.

- It significantly shortens scoping tasks.

- It quickly sets high-level design direction that saves production costs.

Strategy #3 in play: “Could This Be You? Final Episode”

The scene: Jennifer has been asked to quickly produce a cutting-edge, highly engaging learning solution designed to explain an upcoming organizational change that is so significant that it will impact all employee roles in some way. Due to its criticality and high visibility, many leaders are invited to the initial solution identification meetings. The solution must hit the mark. Pressures are extremely high to ensure the solution is successful. After brief initial discussions, it is clear that the leaders are not in close agreement. Conversations are spinning and at times digressing. Much of the conversation is about needed tools and technologies to make this solution happen. We enter the situation, as Jennifer is sharing the problem with her boss…

Jennifer: Ugh! Everyone seems to be talking about everything about the outcomes of this project except for what really matters.

Manager: What really matters?

Jennifer: What the learner will learn! What they will do after they take this training.

Manager: How can you tell them that?

Jennifer: Well, maybe I can make a list of the learning objectives and explain what the learner will be able to do after they complete the training.

Pause. Let’s rewrite this scene. Imagine Jennifer used the Learner Impact Rater to help align success expectations.

We re-enter the conversation with her boss …

Jennifer: In 15 minutes, we gained agreement that we’d align all design components to meet a Level 4. George, who had been so focused on discussing how social media elements would be used, was quickly able to turn his attention to how he preferred the learner to respond. I’m very pleased. The conversation was brief but focused.

Manager: How did everyone else in the meeting respond?

Jennifer: Very actively. It seemed they could quickly see the impact. It helped everyone feel that progress had been made and design could continue quickly.

Summary

Defining and aligning success and quality are the important learning design consulting skills a designer needs in the early stages of creating e-Learning solutions. These strategies, useful for many roles found within e-Learning projects (not just for designers), have been highly successful and are extremely easy to implement. Ultimately, they speak to the importance of learner-centered outcomes and the value of clear, timely, and targeted consulting communications.

References

Gallo, Carmine. 2010. The Presentation Secrets of Steve Jobs: How to be Insanely Great in Front of Any Audience. Chicago: McGrawHill.

Heath, Chip, and Heath, Dan. 2007. Made to Stick: Why Some Ideas Survive and Others Die. New York: Random House.

Prochaska, James, and DiClemente, Carlo. 1982. Trans-theoretical therapy — toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 19(3):276-288.