Just because your learners are present and participating, don’t assume they are into the learning experience in a big way. As e-Learning designers strive to create highly interactive courses, it’s important to remember that interaction is not necessarily education.

Interaction, as defined by Steven Tello (see references), is directed communication regarding course content and topics between the instructor and students or among students in the online course, and has been the focus of many studies of online learning, particularly in its earliest stages of development. As the delivery system has matured, researchers are realizing that interaction does not necessarily facilitate Learning.

Anthony Picciano found that in online-Learning environments, interaction alone failed to adequately define the quality of communication and its influence; and Randy Garrison and Marti Cleveland-Innes demonstrated that interaction did not ensure inquiry learning or cognitive presence. In assessing the quality of communication among online learners, Holly Brower found that in her asynchronous classes, many online students know that the system tracks the number of times they log on and make posts to forums, so they offer many empty comments to create the impression of active learning.

Nikki Leonardi at Hudson Staffing reported on a poll of 1,674 U.S. workers in January of 2006. The survey asked learners what they thought of their last employer-provided training experience. Roughly two-thirds said it was a good (34%) or great (26%) use of their time, while the other third said it was only a fair (22%) or a total waste (12%) of their time. Even more surprising was the 44% of respondents who did not plan on participating in career-related education or training in the following year. At a time when the economy is faltering, and organizations once again seek to trim a bulging employee development budget, such results, although limited in interpretation and usefulness, are disconcerting, particularly when applied to the $109 billion spent on workplace learning last year.

E-Learner engagement

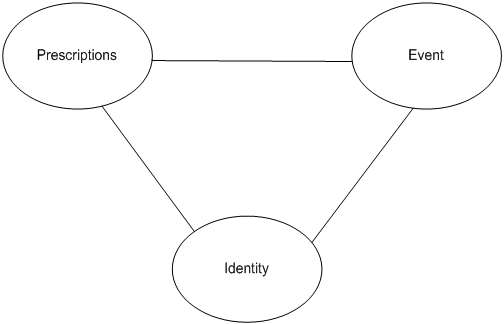

I believe that a more potent component of online-learning success is engagement. Rather than just building highly interactive e-Learning courses, we must also focus on building highly engaging courses. The construct of self-engagement was derived from the triangle model of responsibility by Thomas Britt, and can be seen in Figure 1. Britt has found that engagement is evident when an individual feels a sense of responsibility for, and commitment to, a performance domain, so that performance matters to the individual. The triangle model specifies that individuals are most likely to feel personally engaged in an event when there are strong linkages among the three factors:

- Prescriptions or guidelines of the event are clear and well-defined (strong prescriptions-event link)

- The guidelines are viewed as relevant to the learners' role or identity (strong prescriptions-identity link)

- The individual has personal control over the event (strong identity-event link).

Figure 1 The Triangle Model of Responsibility

Many positive outcomes in performance are linked to engagement. Steven Brown and Thomas Leigh found that when individuals are personally engaged in an activity, they have more stamina; they will try harder when facing an obstacle, and perform better. L. Dee Fink found that engaged learners are also more likely to apply the learned concepts and transfer them to new situations. Thomas Britt found that engagement has implications for motivation and performance and the emotional consequences following the outcome of performance. Personal engagement in an activity magnifies the emotional consequences of succeeding versus failing at a task, because performance outcomes have greater implications for the individual’s identity. In other words, engagement makes people care about their performance; it makes them want to do their best.

Building learning engagement

Assuming that you agree that engagement is a desirable outcome in e-Learning, how do you go about building it into your course design? Here are some strategies and their linkages to the Triangle of Engagement.

Identity-event link

The identity-event link refers to the extent to which the individual has personal control over the event, such as being able to foresee the consequences of the event and intentionally producing the outcome. A strong identity-event link exists when the individual believes that he or she has personal control over a given event. A weak identity-event link exists when the individual feels little control over his or her performance, because someone else is simply telling the individual what to do. Design factors that contribute to a strong identity-event link are:

- Goal setting: Ask learners to set “SMART” goals for themselves before the course begins.

Specific: Don't be vague. Exactly what do you want?

Measurable: Quantify your goal. How will you know if you've achieved it or not?

Attainable: Be honest with yourself about what you can reasonably accomplish at this point in your life – along with taking into consideration your current responsibilities.

Realistic: It's got to be do-able, real, and practical.

Time: Associate a timeframe with each goal. When should you complete the goal?

Periodically during the course, and at the end of the course, have learners assess their progress.

- Incorporate scenarios, simulations, and problem-based learning events into your course design. Learners will feel immersed in learning experience rather than having information given to them. A simple way to engage learners is to open your course with a scenario or problem to solve. Then, supply learners with a knowledge base that they access as needed to resolve the issue. You will find a sample scenario in Sidebar 1 that I have used successfully in my Training Evaluation and ROI course. In Sidebar 2, you will see an exemplary sample of student work based on this challenge.

This is a scenario I used in my Training Evaluation and ROI online course to engage learners.

Here you will be contracted as an outside consultant to work with your first client. She needs help selling the ROI process to top management. Read the scenario below:

Meeting 1: The Heat is On . . .

If you toss a frog into a pot of boiling water, it will jump right out. But if you place it in lukewarm water, and slowly raise the heat, it will relax, until it’s too late. The training division at Hart Industries, a mid-sized manufacturing firm, has been floating in a pot of lukewarm water for several years. They have a huge budget, lots of freedom, and top management has been very pleased with the efforts of the department, but today their pot has begun to boil.

Sandra Wright, the Chief Learning Officer, storms into her office waving a copy of an article from Fortune Magazine titled, “Does Your Training Department Need to Go on a Diet?” Pictured is a cartoon character of a sumo wrestler shoving dollar bills into his mouth. His t-shirt, barely covering his bulging middle, says “Training Department.”

According to the author, corporations spend billions annually to develop their employees, but most of these dollars are wasted. Several line employees and managers told the writer that they learned nothing of value in the corporate training classes they attended, and find them to be a huge waste of time. Two of these individuals were former employees of Hart Industries. They said, “Every penny spent on the production line is accounted for, but when it comes to training, they have no clue where there money is going. Hart might as well take their training dollars and flush them down the toilet for all the good they are doing.”

The writer advised leaders to take these comments to “Hart,” and eliminate the excess in their training areas. He went on to describe one company that eliminated all training entirely and took the money they saved and gave it to their employees as a year-end bonus. Another company hired a team of consultants to formally evaluate each of the training programs they deliver. They used the results to eliminate unnecessary programs, and to improve the value of those that remained.

Hart’s Senior V.P. of Human Resource Management, Sandra’s boss, is livid. The President of Hart Industries has demanded an explanation. Tomorrow Sandra must meet with top management to discuss the article and formulate a response. They want to know why she has no hard data on training outcomes, and exactly how she plans to handle evaluation in the future.

Fortunately, Sandra has some extra money in her training budget, and she decided to hire a consultant to help her deal with her crisis. That’s where you come in. You meet with Sandra, and first help her develop a list of speaking points about ROI that she can present at her meeting tomorrow. Next, you work with her to develop a plan for initiating an evaluation strategy.

During your meeting, Sandra says, "We have three major programs that we'd like to evaluate this period. All are costly to deliver, but we think they have an important impact on our company. The three programs are our Coaching for Business Impact, Stress Management, and Meeting Skills Training. Design of all three programs is very good, and they have been very successful in the past. People love them, and we think they have a strong impact on our success, but we just can't prove it. That's why we need you. We need to conduct a Level 1 through 5 analysis of each program. I have included detailed documentation regarding each program in the files that follow."

You say, "I'd like to begin by analyzing just one program at this time. I think that conducting a full ROI analysis of all three is a bit premature."

Sandra agrees, "You're right. Let's start slowly and do it right. Why don't you look over the documentation for the three programs, and then choose one to start with?"

"Great!" you say. "I will select a program and create a data collection plan for you by our next meeting."

"Wow! You work fast. I knew you were the right person for the job."

(End of Scenario)

Here’s what you need to do:

- Describe the ROI process to Sandra, and identify the types of services you will provide in conducting a level 1 through 5 ROI analysis.

- Identify one of the three courses you will evaluate. A description of each course is in the next document.

Prepared by Mickey Mantas, M.A. Training & Development, Roosevelt University

Currently, Instructional Design Manager with Sears, Roebuck, & Company, LLC. Used with permission of the author.

Ms. Sandra Wright, CLO

Hart Industries

Ms. Wright,

You find yourself in a predicament that many training departments also face – proving the fiscal value and the satisfaction level of your training programs. You, or your supervisors, may know little about the straightforward methods available for building evaluation data into your programs. There are also many ways to improve participant satisfaction. When you clarify the purpose of the training programs, it will make learning objectives more specific. As a result, you can collect measurement data consistently across diverse programs. This means that you will be ready for the type of conversation you are set to have very soon.

First, you must remember that company strategy ties to performance strategy, which ties to performance objectives, which ties to training program measurement and evaluation. You use evaluation data to help make better decisions and take action, which is something that is probably very familiar to you. Using a systematic method for planning your programs, and for reviewing your past programs, will help you to determine the value of these programs to the organization.

Here are my recommendations:

- Identify a reasonable sample of programs conducted over the last year that span a variety of topics, duration, audience, and delivery methods. If you sampled approximately 10-20% of the total number of programs for your evaluation, assuming you have included a variety, you will get a good picture of the overall results.

- Pull your files on these programs.

- Create a spreadsheet that will summarize your findings based on the next steps below. You might feel compelled to focus on the fiscal results of program impact, but this is not the correct approach. You will not be able to determine the financial impact for all of the programs, even if you’re looking at a sample. You should focus on each level of the ROI process identified below.

- Make notes for yourself on key points you’d like to communicate, such as behavioral patterns in departments that have participated in programs. Describe any periods of business or departmental shift in priorities, and any reasons why the effectiveness of these programs was hindered.

- Be optimistic, and identify methods for incorporating evaluation criteria into future programs.

- Remember that you are trying to earn the respect of key stakeholders; therefore, careful attention to collecting data that is important and pertinent, and communicating the results in a clear and timely way is critical. Plan your work, and reflect on the results before the big meeting.

- Do not communicate the results of your training outcomes as the training department’s results! The training department enables outcomes, but does not control the outcome of the participants’ performance as a result of completing the program.

- Apply an evaluation process model to the sample of programs; For each program:

- Review objectives of each program

- Keep objectives in mind when summarizing evaluation results.

- Collect baseline data on what made this program a necessity.

- Collect and summarize data for each program based on an ROI (Return on Investment) framework. Since you will be summarizing information on past programs, data for Levels I, II and possibly III will likely already exist in your files. You will need to do follow up with participants in your sample programs to complete Levels III and IV, if you have not already done this. Determine which level is most important to management for each program you evaluate.

- Level I – Reaction – Summarize “smile sheets” or day-of-program evaluation sheets for participant overall satisfaction with the program. Since there was a comment that “...nothing of value is being learned, and that training was a waste of time...,”, spend a little more time reviewing at this level. Perhaps you might have the answers to the question of satisfaction here?

- Level II – Learning – If there were any tests given during the programs, also called Criterion-Referenced tests, summarize the results for each program to determine whether the program produced any effect on participants acquiring knowledge or changing behavior.

- Level III – Job Application – Summarize for each program whether the new knowledge acquired is being used on the job. Use follow up surveys, questionnaires, small focus groups, and observation to get this data.

- Level IV – Business Impact – Summarize how each program produced a change in key business measures, or what the consequences were of doing something different because of the program. You might need the help of managers for this data. Items that you will look at include production reject rates, harassment complaint figures, changes in sales, etc. Consider using trend analyses to summarize results for each program, and focus on the effects of the program.

- Level V – Return on Investment – Choose programs from your sample which had a long life cycle (18 months or longer), were most important to your company’s operating goals, were very expensive to implement, or had a large target audience for this level of impact. Choosing smaller programs for Level V evaluation may not be the best use of your time, as collecting this degree of data may be complicated at your company.

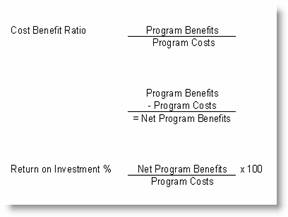

- Convert data to monetary figures

- Determine program costs, including facilitator fees, and costs related to materials, travel, salaries and benefits of participants, overhead, needs assessment, design, development, and technology. You will need to prorate some of these costs.

- Determine program benefits by assigning monetary value. Focus on a unit of measure; determine the value of each unit, calculate the change in performance of the measure, determine the annual amount of the change, and calculate the total annual value of the improvement.

Calculate your Net Program Benefits; Calculate ROI. (See Figure 2.)

- Summarize intangible benefits such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and increase in customer satisfaction, etc.

- Summarize, if possible, opportunity costs (defined as the cost of an opportunity foregone) of not offering the programs to your organization.

This degree of evaluation may not fit into your comfort level, or it may preclude you from performing your other program planning which is still vital to the organization. If this is the case, I would be most happy to consult to your organization and complete a full report on my findings. If you wish, I can also include case studies that prove the validity of the types of programs you are offering, as well as benchmark data on other companies in your industry.

Best of luck!

Mickey Mantas

Prescription-event link

The prescription-event link refers to the need for a clear and well-defined set of guidelines for the learning event. An example of a strong prescription-event link would be a detailed syllabus that outlines grading policy and expectations. An example of a weak link would be a worker participating in a training program without clear objectives or goals. Here is how you can ensure a strong prescription-event link in your design.

- Start with strong, measurable objectives. Ideally, link each objective that you write to practice and assessment. Too often, objectives are vague and extraneous to what really happens within a course. Make your objectives work for you by ensuring that you have observable and measurable ways to reach them during your course design. For example:

Objective: Learners will apply the four-factor model of customer problem resolution with 90% accuracy.

Practice: Present learners with a series of written, video, or role-played vignettes of customer problems. They then solve them using the four-factor model of problem resolution.

Assessment: Assess performance using observation, course feedback (for example, in a branching story line, learners make choices and the accuracy of their choices is assessed), or with an electronic or paper and pencil test.

- Scaffold learning with worked examples. Although lists of expectations are helpful, as are rubrics and performance goals, a worked sample that demonstrates success will help your learners clearly see what they need to do. The example can be a written sample, or, in skills training, a visual sample of exemplary performance. I have done exactly this for item 2 under “Identity-event Link” by providing a sample of a scenario and the correct response (see Appendix 1 and 2).

Identity-prescription link

The identity-prescription link refers to the extent to which a set of prescriptions or rules are relevant to an individual’s identity or role. In the learning environment, this refers to the extent that individuals feel that training is important to them personally, and that it will directly contribute to their success. All too often, learners feel that training is a waste of time because they already know, or think they know, the skills taught, or they do not feel that the skills directly affect their job performance. Here are some design considerations to strengthen this linkage:

- Get top management buy-in: Individuals will feel more responsible in situations that they view as personally important, or for events that have greater consequences.

- Add work-based learning components: Directly link the learning experience to current workplace problems or issues, so learners see the immediacy and value of the learning experience.

- Initiate a competency-based learning program. Begin by measuring learner competencies, and then create an individualized training prescription that directs learners to those courses or course components that will help them achieve only necessary competencies.

Measuring engagement

Assuming you met the requirements of the Triangle of Responsibility, and you think this time you’ve engaged your learners, not just kept them busy, how do you find out if you’re correct? The answer of course, is both simple and complex. You ask them. Steven Brown found that he could accurately assess engagement by asking questions that relate to the Triangle of Responsibility. For example, you might ask trainees to respond to the following statements:

- The training is relevant to my job (prescription-identity link)

- I understand the objectives of the training (prescription-event link)

- I feel that I am in control of my learning experience (identity-event link)

Commitment and responsibility are also important factors to assess, as Britt and his colleagues described in their 2006 article. Therefore, you might also ask:

- I feel committed to learning more about (topic)

- I feel responsible for my learning success

This survey might be delivered in many ways – a brief poll shortly after training has been introduced, a small or large group discussion, or a paper-and-pencil or electronic survey.

Return on engagement

Your measure of engagement can also serve as an outcome variable in course evaluation. We often find that in addition to satisfaction, learning, transfer, and monetary impact due to increased job performance, engagement affects additional variables and factors such as job satisfaction or turnover. Increased learner engagement could be a key outcome to include in your course assessment. At a time when many organizations are seeking to increase employee engagement, increased learner engagement will provide a direct link to this organizational goal.

References

Britt, Thomas W. (1999). Engaging the self in the field: Testing the triangle model of responsibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 696-706.

Britt, Thomas W. (2003a). Aspects of identity predict engagement in work under adverse conditions. Self and Identity, 2, 31-45.

Britt, Thomas W. (2003b). Motivational and emotional consequences of self engagement: Dynamics in the 2000 presidential election. Motivation and Emotion, 27, 339-358.

Britt, Thomas W., Thomas, Jeffrey L., and Dawson, Craig R. (2006). Self-Engagement Magnifies the Relationship Between Qualitative Overload and Performance in a Training Setting. Journal of Applied Psychology, 36, 2100-2115.

Brower, Holly H. (2003). On emulating classroom discussion in a distance-delivered OBHR course: Creating an on-line-Learning community. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 2, 22-36,.

Brown, Steven P., and Leigh, Thomas W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationship to job involvement, effort, and performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 358-368.

Fink, L. Dee (2002) Beyond small groups: Harnessing the extraordinary power of learning teams. In L.K. Michaelsen, A.B. Knight, L.D. Fink (Eds.), Team-based learning: A transformative use of small groups (pp. 3–25). Praeger: Westport, CT.

Garrison, D. Randy, & Cleveland-Innes, Marti (2004). Critical factors in student satisfaction and success: Facilitating student role adjustment in online communities of inquiry. In Elements of quality online education: Into the mainstream. Volume 5 in the Sloan C Series, Eds. J. Bourne and J. C. Moore, 29–38. Needham, MA: The Sloan Consortium.

Leonardi, Nikki (2006). Workplace Training Often Falls Short Despite Interest and Investment. Retrieved February 1, 2008 from http://us.hudson.com/node.asp?kwd=01-18-06-workplace-training

Picciano, Anthony G. 2002. Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks 6 (1): 21–40.

Tello, Steven (2007). An analysis of student persistence in online education. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 93, 47-63.