In the midst of all the excitement regarding new learning technologies such as 3-D virtual worlds and mobile learning, many companies continue to struggle with fundamental obstacles. These obstacles prevent them from implementing effective asynchronous e-Learning strategies. In fact, some of these barriers, which I discuss in this article, will invariably lead to poor strategies for learning in virtual worlds or on mobile devices. New tools and technologies will not mitigate a poor e-Learning strategy.

These organizations need to first overcome the typical barriers that we have seen in asynchronous e-Learning development before leaping to a new learning technology platform. Organizations that are already creating highly “effective, efficient, and engaging (e3)” e-Learning, applying the research and best practices in the field, are ready to move forward, as M. David Merrill pointed out in a 2009 article in Educational Technology. (See References at the end of this article.) However, organizations that are struggling to overcome the obstacles that continually lead designers to develop information-centric page-turners, or to convert classroom slide presentations to e-Learning, can use the information that follows to great advantage.

We have been sufficiently instructed for decades

So why do organizations continue to produce “shovelware” (Fraser 1999), by taking information and shoveling it onto the Web in the form of a page-turner which is “warmed over, insipid, [and] pedagogically pointless (Fraser 1999)?” It is certainly not for a lack of available research and industry best practices. Experts have reminded us for decades that information-centric page-turners provide a very low learning and business impact. Some of the more famous quotes regarding poor e-Learning design include the following:

- “Information is not Instruction.” (Merrill 1997)

- “Boring instruction is not effective instruction.” (Allen 2003)

- “People learn by doing.” (Aldrich 2005)

In 2001, Marc Rosenberg provided the industry with a foundational book for implementing e-Learning strategies and a list of recommendations for improving e-Learning design that are still relevant today. Rosenberg recommended that e-Learning should take into account:

- learner motivation

- activities that allow learning by doing through authentic challenges

- opportunities to learn through mistakes

- appropriate coaching and feedback

Dr. Michael Allen provides some of the same recommendations in his book dedicated to implementing effective e-Learning design strategies.

In addition, innovations in e-Learning tools now allow developers to rapidly create learning interactions that support a variety of instructional strategies. The programming language included in Adobe Flash, Action Script, is now an object-oriented language allowing for development of reusable learning objects, game based learning activities, and complex simulations.

So, with all of the innovations in e-Learning development tools, and decades of literature on how to design effective e-Learning, why would a training organization choose to implement a page-turner e-Learning strategy? In my opinion, the principle of “triadic reciprocal determinism” provides insight about organizational decisions regarding the development of e-Learning strategies. In addition, three other factors also contribute to poor learning strategy decisions. After exploring these factors in detail, I will provide some practical recommendations for overcoming the obstacles that prevent organizations from developing effective e-Learning strategies.

What cognitive science tells us about our decisions

Have you noticed that many suburban homes in the U.S. are beginning to look very much alike? Every one of them seems to have the same trim design on their walls. The kitchen and bathroom fixtures look the same. The landscaping has the same style of shrubs. The reason seems to be logical. The homeowners all shopped at the local hardware superstore.

The ease of driving a few miles to the local hardware store and purchasing what is on sale has influenced interior design decisions. Likewise, the marketing of “Do It Yourself” (DIY) tools, together with a slumping economy, created more weekend construction workers. These external environmental factors have influenced purchasing behaviors, as well as the desire to learn how to use the products and tools now available. In fact, some of the hardware superstores now offer live in-person and online training to further influence the purchasing behaviors of their clients.

In addition to these external factors, homeowner skills, knowledge, and personality traits will also determine the choice of the strategy of do-it-yourself home repair versus hiring a contractor. Cognitive science can explain these behaviors.

Triadic reciprocal determinism

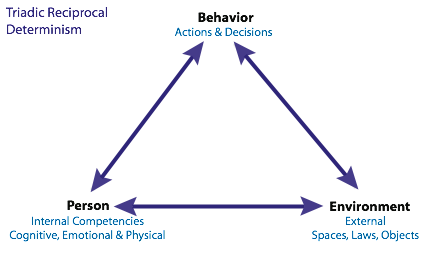

Albert Bandura (1986) provided a model for human behavior that can help explain why many homeowners make decisions such as to purchase power tools and choose to become a do-it-yourself carpenter. Our internal person, which includes our personality type, as well as our cognitive and emotional competencies, influences our actions. Furthermore, our external environment also influences our actions. Our external environment includes physical spaces, objects such as tools, policies, or laws, and the actions of the people within our environment. Figure 1 illustrates Bandura’s model of “triadic reciprocal determinism.”

Figure 1: Bandura’s Triadic Reciprocal Determinism Model

Each corner of the triangle has an influence on the others. Our actions and decisions influence both our personal attributes and our environment. If you choose to take courses on carpentry, you will obtain the skills of carpentry. If you choose to purchase do-it-yourself tools and products, then manufacturers will continue to develop and sell these products.

Our personal attributes influence our actions and our environment. If you have skills in carpentry, you are more likely to take on home remodeling projects that require skills in carpentry. If you prefer to look at soothing light colors, you will paint the interior of your home with soothing light colors.

And finally, our environment influences our actions and our personal attributes. Proximity to a large hardware store, your financial status, and what tools you own, will influence your decision to remodel the home yourself.

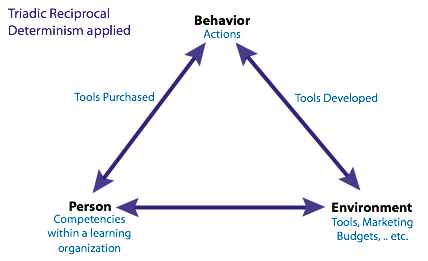

Now apply this model to e-Learning development. If you lack the skills necessary to design e-Learning interactions, but are very familiar with developing instructor-led presentations, your actions will lead to an e Learning course that looks a lot like an instructor-led presentation. If you lack skills in programming, you will choose to purchase tools that do not require programming. If your organization has a low budget, you will choose to look for DIY tools rather than to hire external experts or hire full-time staff. If tools exist that enable the rapid conversion of slide decks to e Learning you might decide that there is no need to learn about instructional technology or programming and will choose not to learn these skills.

Figure 2: Applying triadic reciprocal determinism

This model also suggests an explanation as to why e-Learning tool vendors have developed tools that do not require programming nor instructional design. In turn, the existence and success of these tools may be a factor that can influence poor e-Learning strategies.

Three factors that contribute to poor learning strategy decisions

Bandura’s model suggests three specific factors that contribute to organizations making poor learning strategy decisions. These are:

- Existence of rapid e-Learning tools: E-Learning tool vendors have responded to the skills gap in computer programming and e-Learning design by creating tools that require little technical expertise and no instructional design expertise. In other words, the tools enable users to create “shovelware” more rapidly. Tools that allow for rapid conversion of classroom slides to e-Learning represent this classification of tools.

- Competency gaps in Computer Science: The ability to design creative e Learning interactions also requires knowledge of the technology and its capabilities. For example, how can someone design a reusable-learning-object strategy if he or she has no knowledge of object-oriented programming and how to use Flash or other programming languages to implement it? In addition, if the designer does not understand the capabilities and limitations of SCORM, how can they design the learning to leverage SCORM appropriately?

- Competency gaps in e-Learning design: Although an instructional designer or trainer may have the skills to write measurable learning objectives, he or she may not have the skills to interpret those objectives into effective e-Learning technology strategies. This competency requires skills in creative design and synthesis.

e-Learning tools and their impact on e-Learning strategy

For over ten years, Dr. M. David Merrill and his ID2 research group worked on a project to automate the process for designing effective instructional strategies into e-Learning development tools. For ten years, Utah State University hosted an annual event to discuss the ID2 research findings with the academic and professional community. At the 1998 event Dr. Merrill invited a series of e-Learning authoring tool vendors and presented the challenge of automating the design process into their tools. Merrill summarizes what happened:

“The challenge I posed to the representatives of three of the most prominent vendors of authoring systems was this: ‘Automating Instructional Design: Can we? Should we? Will we?’ We wanted to know if these vendors would pursue the line of research and development that we had pursued for the past decade. Basically, the answer they gave was: ‘We could, we should, and we won't!’ The reasons were that these companies were market driven. We had been pursuing the development of automated tools to accompany Macromedia's Dreamweaver product. But Macromedia dropped the project after they did a series of focus groups with potential customers. The information they gleaned from their potential customers was that they just wanted someone to tell how to do the nuts and bolts of the tool; they did not want smart tools. They wanted to do their own instructional design. Following this conference our group disbanded over the next year or two and our dream of ‘an order of magnitude improvement in productivity coupled with an order of magnitude improvement in instructional quality’ aided by intelligent authoring tools faded into history. (Merrill 2010)”

As a result, beginning in the mid 1990s, the major e-Learning authoring tool vendors and developers did what any company would do: they listened to their customers. I believe the impact of that decision has contributed to the continual production of information-centric page-turners as an e-Learning strategy.

What tool choices do we have?

E-Learning developers do have choices in the selection of tools. There are four basic categories of e-Learning tools to choose from:

- Template-based tools allow the developer to select and sequence templates, each with a different presentation objective. You can organize templates as lessons and pages in lessons. Navigation is normally a Menu, and Back and Next buttons. Tools like ProForm™, Unison™, and Raptivity™ fall into this category. Some templates simply present content, and others engage the learner in an activity such as memory recall, categorization, or a branching decision tree.

- Power Point™ to Flash™ conversion tools allow developers to take a Power Point slide presentation and convert it to a Flash-based e-Learning course. The course normally uses a Menu, Back, and Next buttons for navigation. These tools allow the developer to add narrations, quizzes, and other presentation objects such as animations or movies. Tools like Articulate Presenter™ and iSpring Presenter™ fall into this category.

- Screen capture tools allow the developer to either capture or import screens as slides. The developer can then add navigation and narration. Navigation is not limited to Back and Next buttons. The learner can navigate through the slides by clicking on buttons superimposed on the screen shots. These tools allow for limited branching and quizzing. Camtasia Studio and Adobe Captivate fall into this category.

- Graphics tools with a built-in programming language allow developers to build graphics and animations, as well as program learning interactions. Adobe Flash is somewhat alone in this category and professional e Learning vendors predominantly use it. This tool requires the skills of a graphic artist and a programmer.

Despite all of the tools options, if the user lacks the proper competencies to use these tools, he or she runs the risk of creating “shovelware.”

Competency gaps and their impact on strategy

Carliner and Driscoll (2009) suggest that there is a relationship between innovations in e-Learning authoring tools and the decision to assign someone to an e-Learning development project. A trend, cited in a 2003 ASTD report, indicates that, more and more, organizations task non-instructional designers with the development of e-Learning (Van Buren, 2003). As a result, individuals without the appropriate skill set are tasked to develop e-Learning.

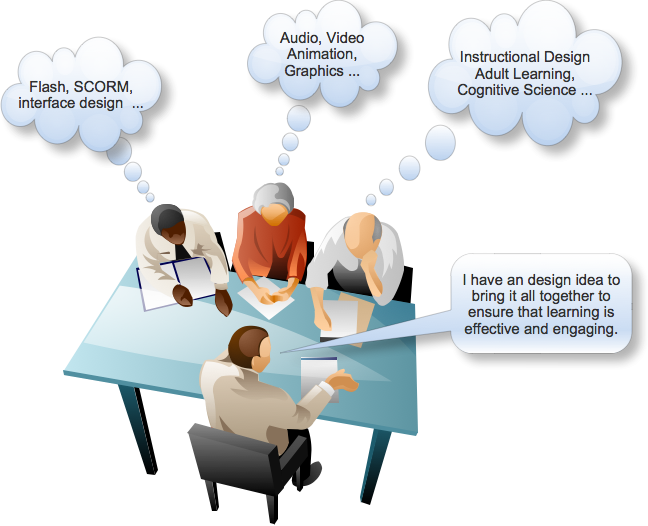

Bringing together the disciplines needed to create an effective online learning application requires competencies in instructional design, cognitive science, media arts, and computer science. In addition you need someone who has the ability to analyze the instructional needs-analysis data and synthesize a solution bringing all of these competencies together. (See Figure 3.) Daniel Pink (2005) points out that the skill of synthesis and design is not a skill held by many people. What I have found, as an e-Learning manager for nine years, is that the competency to design and synthesize e-Learning solutions is a skill that is both in short supply and difficult to teach.

Figure 3: Synthesis of multiple disciplines to design a solution

If a learning organization lacks an individual with these skills of design and synthesis, one solution is to purchase tools that allow you to leverage the skills you have. However, tools cannot always make up for gaps in knowledge. Consider that many people, despite their lack of skills in woodworking, decide to purchase and use dangerous power tools. As a result, nearly 32,000 home owners seriously injure themselves each year with power tools used in the home (Newsome, 2007). Despite the risks of having low impact on learning, people continue to purchase e-Learning development tools and immediately begin constructing e-Learning without receiving training in e Learning design.

What can organizations do to change these behaviors and actions?

Learning organizations need to begin evaluating their own capabilities by using tools such as performance analysis and training needs analysis (Mager, 1998). Do we lack the competencies to follow the research and best practices presented to us by the experts in our field? If we discover that we have made choices to develop information-centric page-turners, we need to ask the question, “Why?” We may have very good instructional designers who come up with creative learning interaction designs, but do not have the programming skills to implement the design.

Table 1 contains some suggested mitigations to the problems I have discussed in this article.

|

Problem |

Mitigation |

|

We have skills in instructional design but lack skills in programming |

Learning how to program in Flash or other programming tools is a very complex skill. Consider outsourcing this skill. Evaluate a vendor’s capabilities and pricing by looking at examples of their work. Ask for an example of a high-end simulation or learning game. |

|

We have skills in instructional design but lack skills to design a creative e Learning solution. |

This skill requires the ability to analyze needs-analysis data, consider all of the science, and synthesize a solution. One can learn this skill, and there are training programs and degree programs to teach it. However, I recommend outsourcing this task to a local company with a person who possesses this unique skill of design and synthesis. Ask for sample work, or work with the vendor on a project to see how creative they really are. Challenge them to explain the instructional reason for the design. |

|

We have a low budget so we cannot afford to hire vendors to outsource the skills of design and programming. |

Maybe you can't afford to outsource your entire problem, but you might be able to outsource some of it. Break the task up into components. The first component is instructional design. Keep instructional design in house. Learn how to conduct a needs analysis and write measurable learning objectives. Keep the interface between instructional designer and subject matter experts in house if you can. Your in house team can be responsible for writing the content. Secondly, find a design consultant who can work with you on your designs. This person should have a background in both programming and creative design. Finally, outsource the programming to a vendor that offers low cost programming. You will find companies located in India that offer reasonable prices for programming and e-Learning development. |

Conclusion

If a learning organization has the vision to take their e-Learning to the level of experiential learning within authentic contextual challenges, simply purchasing rapid development tools may not be the way to achieve this vision. Learning organizations need to recognize that effective e-Learning requires skills in instructional design, cognitive science, media arts, and computer science and the ability to synthesize all of these skills. If learning organizations do not have these skills in house they should consider building the business case to develop the skills, hire someone who has these skills or outsource the skill.

References

Aldrich, C. 2005. Learning by Doing: A Comprehensive Guide to Simulations, Computer Games, and Pedagogy in e-Learning and Other Educational Experiences. San Francisco, CA: Pfeiffer.

Alistair B. F.1999. Colleges Should Tap the Pedagogical Potential of the World-Wide-Web. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 45(48), B8. Retrieved May 6, 2010, from Research Library. (Document ID: 43623001).

Allen, M. W. 2003. Michael Allen's Guide to e-Learning: Building Interactive, Fun, and Effective Learning Programs for Any Company. New York: John Wiley.

Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall.

Driscoll, M. & Carliner, S. 2009."Who's Creating the E-Learning." In Michael Allen's 2009 e-Learning Annual, 43-56. Vol. 1. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Fraser, A. B. (1999). Colleges should Tap the Pedagogical Potential of the World-Wide-Web. The Chronicle of Higher Education, 45(48), B8.

Mager, R. F. 1988. Making Instruction Work, or Skillbloomers. Belmont, Calif.: Lake Books.

Merrill, M. David, Li, Zhongmin, & Jones, Mark K. 1991. Second Generation Instructional Design (ID2). Educational Technology 30, No. 1: 7-11.

Merrill, M. David. 1997. Instructional Strategies That Teach. CBT Solutions, Nov/Dec, 1-11.

—. 1999. Instructional Transaction Theory (ITT): Instructional Design Based on Knowledge Objects. In C. M. Reigeluth (Ed.), Instructional Design Theories and Models: A New Paradigm of Instructional Theory. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

—. 2009. Finding e3 (effective, efficient, and engaging) instruction. Educational Technology, 49(3),15-26.

—. 2010. "Question about a Summer Institute in the 90s." E-mail message to author. April 13, 2010.

Newsome, M. 2007. He Took On the Whole Power-tool Industry, Gizmos and Gadgets article - Inc. article. Small Business and Small Business Information for the Entrepreneur. http://www.inc.com/magazine/20050701/disruptor-gass.html (accessed April 27, 2010).

Pink, D. H. 2005. A Whole New Mind: Moving From the Information Age to the Conceptual Age. New York: Riverhead Books.

Rosenberg, M. J. (2001). E-learning: strategies for delivering knowledge in the digital age. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Van Buren, M. 2003. State of the Industry. Alexandria, VA: ASTD.